Warld War II

The "Scots" that wis uised in this airticle wis written bi a body that haesna a guid grip on the leid. Please mak this airticle mair better gin ye can. |

| Warld War II | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

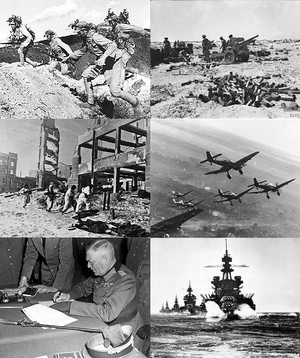

Clockwise frae tap left: Cheenese forces in the Battle o Wanjialing, Australian 25-pounder guns durin the First Battle o El Alamein, German Stuka dive bombers on the Eastren Front winter 1943–1944, US naval force in the Lingayen Gulf, Wilhelm Keitel signin the German Instrument o Surrender, Soviet troops in the Battle o Stalingrad | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Allies Client an puppet states |

Axis Co-belligerents Client and puppet states | ||||||

| Commanders an leaders | |||||||

|

...an ethers |

...an ethers | ||||||

| Casualties an losses | |||||||

|

Militar dead: Ower 16,000,000 Civilian dead: Over 45,000,000 Total dead: Over 61,000,000 (1937–45) ...further details |

Militar dead: Ower 8,000,000 Civilian dead: Over 4,000,000 Total dead: Over 12,000,000 (1937–45) ...further details | ||||||

Warld War II, or the Seicont Warld War (aften abbreviatit as WWII or WW2), wis a global war that stertit in 1939 an endit in 1945. It inrowed the wappin forces o the warld's naitions—includin aw o the great pouers—at the hinner en formin twa opponin military alliances: the Feres an the Axis. It wis the braidest war in history, an directly inrowed mair nor 100 million fowk frae ower 30 kintras. In a state o "tot war", the major participants funged thair hail economic, industrial, an scienteefic cawpabilities ahint the war brash, erasin the distinction atween ceevilian an militar resoorces. Merkit bi mass daiths o ceevilians, includin the Holocaust (in whilk thareaboot 11 million fowk wis killt)[1][2] an the strategic bombin o industrial an population centres (in whilk thareaboot ane million fowk wis killt, includin the uise o twa nuclear wappens in combat),[3] it resultit in an estimate 50 million tae 85 million fatalities. Thir made Warld War II the deidliest pingle in human history.[4]

The Empire o Japan ettilt tae dominate Asie an the Paceefic an wis awready at war wi the Republic o Cheenae in 1937,[5] but the warld war is generally said tae hae began on 1 September 1939[6] wi the invasion o Poland bi Germany an subsequent declarations o war on Germany bi Fraunce an the Unitit Kinrick. Frae late 1939 tae early 1941, in a series o campaigns an treaties, Germany vinkisht or maunt the feck o continental Europe, an formed the Axis alliance wi Italy an Japan. Follaein the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Germany an the Soviet Union pairteetioned an annexed territories o thair European neighbours, Poland, Finland, Romanie an the Baltic states. The Unitit Kinrick an the Breetish Commonweel wis the anerly Allied forces continuin the fecht agin the European Axis pouers, wi campaigns in North Africae an the Horn o Africae as weel as the lang-rinnin Battle o the Atlantic. In Juin 1941, the European Axis pouers lencht an invasion o the Soviet Union, appenin the lairgest laund war theatre in history, whilk trappit the feck o the Axis' militar forces intae a attrition war. In December 1941, Japan attackit the Unitit States an European territories in the Paceefic Ocean, an swith vinkisht a fait feck o the Wastren Paceefic.

The Axis forderin hautit in 1942 whan Japan lost the creetical Battle o Midway, near Hawaii, an Germany wis defait in the North Africae an syne, decisively, at Stalingrad in the Soviet Union. In 1943, wi a series o German defaits on the Eastren Front, the Allied invasion o Italy whilk rase Italian renooncement, an Allied owerhauns in the Paceefic, the Axis lost the initiative an taen legbail on haun on aw fronts. In 1944, the Wastren Allies invadit German-occupied Fraunce, while the Soviet Union won back aw o its territorial losses an invadit Germany an its feres. Durin 1944 an 1945 the Japanese dreed major reverses in mainland Asie in Sooth Central Cheenae an Burma, while the Allies lamed the Japanese Navy an fangt key Wastren Paceefic islands.

The war in Europe endit wi an invasion o Germany bi the Wastren Allies an the Soviet Union culminatin in the tak o Berlin bi Soviet an Pols truips an the subsequent German uncondeetional surrender on 8 Mey 1945. Follaein the Potsdam Declaration bi the Allies on the 26t Julie 1945 an Japan's refuise o tae renoonce unner its terms, the Unitit States drappit atomic bombs on the Japanese ceeties o Hiroshima an Nagasaki on the 6t August an the 9t August respectively. Wi an invasion o the Japanese airchipelago imminent, the possibility o addeetional atomic bombins, an the Soviet Union's declaration o war on Japan an invasion o Manchuria, Japan renoonced on the 15t August 1945. Sicweys endit the war in Asie, souderin the Allies' tot victory.

Warld War II chynged the warld's poleetical alignment an social structur. The Unitit Naitions (UN) wis estaiblisht fur tae forder internaitional comploutherin an fur tae prevene futur conflicks. The gree-bearin great pouers—the Unitit States, the Soviet Union, Cheenae, the Unitit Kinrick, an Fraunce—became the permanent memmers o the Unitit Naotions Security Cooncil.[7] The Soviet Union an the Unitit States ootcam as rival superpouers, settin the stage fur the Cauld War, whilk lastit fur the neist 46 year. Atween haun, the European great pouers' hank waned, while the decolonisation o Asie an Africae began. Maist kintras whase industries haed been damaged muived taewart economic betterness. Poleetical integration, inspecially in Europe, wis a war ootcome, as pairt o a ettle at endin afore-war laith an creautin a common identity.[8]

Backgrund

[eedit | eedit soorce]Europe

[eedit | eedit soorce]Warld War I haed radically altert the poleetical European map, wi the defeat o the Central Powers—includin Austrick-Hungary, Germany, Bulgarie an the Ottoman Empire—an the 1917 Bolshevik seizur o pouer in Roushie, that hinderly led tae the foondin o the Soviet Union. Atween haun, the veectorious Allies o Warld War I, sic as Fraunce, Belgium, Italy, Romanie an Greece, gained territory, an new naition-states wis creatit oot o the collapse o Austrick-Hungary an the Ottoman an Roushie Empires. Fur tae prevene a futur warld war, the League o Naitions wis creatit in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

Maugre strang pacifist sentiment efter Warld War I,[9] its eftermath still caused irredentist an revanchist naitionalism in several European states. Thir sentiments wis especially merkit in Germany acause o the signeeficant territorial, colonial, an financial losses incurred bi the Treaty o Versailles. Unner the treaty, Germany lost aroond 13 percent o its hame territory an aw o its owerseas possessions, while German annexation o ither states wis prohibitit, reparations war imposed, an leemits wis placed on the size an capability o the kintra's airmed forces.[10]

The German Empire wis dissolved in the German Revolution o 1918–1919, an a democratic govrenment, later kent as the Weimar Republic, wis creautit. The interwar period saw strife atween supporters o the new republic an hardline opponents on baith the richt an left. Italy, as an Entente ally, haed made some post-war territorial gains; houiver, Italian naitionalists wis angert that the promises made bi Breetain an Fraunce tae siccar Italian entrance intae the war wisnae fulfilt in the peace dounset. Frae 1922 tae 1925, the Fascist muivement led bi Benito Mussolini seized pouer in Italy wi a naitionalist, totalitarian, an cless collaborationist agenda that abolisht representative democracy, repressed socialist, left-weeng an leeberal forces, an pursued an aggressive expansionist foreign policy aimed at makkin Italy a warld pouer, promisin the creaution o a "New Roman Empire".[11]

Adolf Hitler, efter an unsuccessfu attempt tae owerthraw the German govrenment in 1923, eventually acame the Chancellor o Germany in 1933. He abolisht democracy, espoosin a radical, racially motivatit revision o the warld order, an suin begoud a massive reairmament campaign.[12] Meanwhile, Fraunce, tae siccar its alliance, alloued Italy a free haund in Ethiopie, that Italy desired as a colonial possession. The situation wis aggravatit in early 1935 whan the Territory o the Saar Basin wis legally reunitit wi Germany an Hitler repudiatit the Treaty o Versailles, acceleratit his reairmament programme, an introduced conscription.[13]

Hitler defee'd the Versailles an Locarno treaties bi remilitarisin the Rhineland in Mairch 1936, encoonterin little opposeetion.[14] In October 1936, Germany an Italy formed the Roum–Berlin Axis. A month later, Germany an Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, that Italy wad jyne in the follaein year.

Asie

[eedit | eedit soorce]The Kuomintang (KMT) pairty in Cheenae launched a unification campaign against regional warlairds an nominally unifee'd Cheenae in the mid-1920s, but wis suin embrulyie'd in a ceevil war against its umwhile Cheenese Communist Pairty allies[15] an new regional warlairds. In 1931, an increasinly militareestic Empire o Japan, that haed lang soct influence in Cheenae[16] as the first step o whit its govrenment saw as the kintra's richt tae rule Asie, uised the Mukden Incident as a pretext tae launch an invasion o Manchurie an establish the puppet state o Manchukuo.[17]

Ower waik tae resist Japan, Cheenae appealt tae the League o Naitions fur help. Japan widrew frae the League o Naitions efter bein condemned fur its incursion intae Manchurie. The twa naitions syne focht several battles, in Shanghai, Rehe an Hebei, till the Tanggu Truce wis signed in 1933. Thareefter, Cheenese volunteer forces conteena'd the reseestance tae Japanese aggression in Manchurie, an Chahar an Suiyuan.[18] Efter the 1936 Xi'an Incident, the Kuomintang an communist forces greed on a ceasefire tae present a unitit front fur tae oppone Japan.[19]

Pre-war events

[eedit | eedit soorce]Spaingie Ceevil War (1936–39)

[eedit | eedit soorce]Whan ceevil war ootbrak in Spain, Hitler an Mussolini lent militar uphaudin tae the Naitionalist rebels, led bi General Francisco Franco. The Soviet Union uphaudit the existin govrenment, the Spaingie Republic. Ower 30,000 foreign volunteers, kent as the Internaitional Brigades, forby focht agin the Naitionalists. Baith Germany an the USSR uised this proxy war as an opportunity fur tae test in combat thair maist advanced wappens an tactics. The Naitionalists wan the ceevil war in Apryle 1939; Franco, nou dictator, remeened offeecially neutral in World War II but generally favoured the Axis.[20] His greatest collaboration wi Germany wis the sendin o volunteers tae fecht on the Eastren Front.[21]

Japanese invasion o Cheenae (1937)

[eedit | eedit soorce]In Julie 1937, Japan capturt the umwhile Cheenese imperial caipital o Peking efter instigatin the Marco Polo Brig Incident, that culminatit in the Japanese campaign tae invade aw o Cheenae.[22] The Soviets quickly signed a non-aggression pact wi Cheenae tae lend materiel uphaudin, effectively endin Cheenae's prior comploutherin wi Germany. Frae September tae November, the Japanese attackit Taiyuan,[23][24] as weel as engagin the Kuomintang Airmy aroond Xinkou[23][24] an Communist forces in Pingxingguan.[25][26] Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek deployed his best airmy tae defend Shanghai, but, efter three month o fechtin, Shanghai fell. The Japanese conteena'd tae push the Cheenese forces back, capturin the caipital Nanking in December 1937. Efter the faw o Nanking, tens o thoosands, gif no hunders o thoosands, o Cheenese ceevilians an disairmed combatants wis murthert bi the Japanese.[27][28]

In Mairch 1938, Naitionalist Cheenese forces wan thair first major veectory at Taierzhuang but then the ceety o Xuzhou wis taken bi Japanese in Mey.[29] In Juin 1938, Cheenese forces stawed the Japanese advance bi fluidin the Yellae River; this manoeuvre bocht time fur the Cheenese tae prepare thair defences at Wuhan, but the ceety wis takken bi October.[30] Japanese militar veectories didnae bring aboot the collapse o Cheenese resistance that Japan haed howpit tae achieve; insteid the Cheenese govrenment relocatit inland tae Chongqing an conteena'd the war.[31][32]

European occupations an agreements

[eedit | eedit soorce]

In Europe, Germany an Italy wis becomin aggressiver. In Mairch 1938, Germany annexed Austrick, again provokin a bittock response frae ither European pouers.[33] Encouraged, Hitler begoud pressin German claims on the Sudetenland, an aurie o Czechoslovakie wi a predominantly ethnic German population; an suin Breetain an Fraunce follaed the coonsel o Breetish Prime Meenister Neville Chamberlain an concedit this territory tae Germany in the Munich Greement, that wis made agin the wishes o the Czechoslovak govrenment, in exchynge fur a promise o nae mair territorial demands.[34] Suin efterwart, Germany an Italy forced Czechoslovakie tae cede addeetional territory tae Hungary an Poland annexed Czechoslovakie's Zaolzie region.[35]

Awtho aw o Germany's statit demands haed been satisfee'd bi the greement, preevatly Hitler wis furious that Breetish interference haed preventit him frae seizin aw o Czechoslovakie in ane operation. In subsequent speeches, Hitler attackit Breetish an Jewish "war-mongers" an in Januar 1939 saicretly ordered a major big-up o the German navy tae challenge Breetish naval supremacy. In Mairch 1939, Germany invadit the remeender o Czechoslovakie an subsequently split it intae the German Pertectorate o Bohemie an Moravie an a pro-German client state, the Slovak Republic.[36] Hitler forby deleevered the 20 Mairch 1939 ultimatum tae Lithuanie, forcin the concession o the Klaipėda Region.

Greatly alairmed an wi Hitler makkin forder demands on the Free Ceety o Danzig, Breetain an Fraunce guaranteed thair uphaudin o Pols unthirldom; whan Italy conquered Albanie in Apryle 1939, the same guarantee wis extendit tae Romanie an Greece.[37] Shortly efter the Franco-Breetish pledge tae Poland, Germany an Italy formalised thair awn alliance wi the Pact o Steel.[38] Hitler accuised Breetain an Poland o tryin tae "encircle" Germany an renoonced the Anglo-German Naval Greement an the German–Pols Non-Aggression Pact.

The situation reakit a general creesis in late August as German truips conteena'd tae mobilise agin the Pols mairch. In August 23, whan tripartite negotiations aboot a militar alliance atween Fraunce, Breetain an USSR stawed[39], Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact wi Germany.[40] This pact haed a saicret protocol that defined German an Soviet "spheres o influence" (wastren Poland an Lithuanie for Germany; eastren Poland, Finland, Estonie, Latvie an Bessarabie fur the USSR), an raised the quaisten o conteenuin Pols unthirldom.[41] The pact neutralised the possibility o Soviet opposeetion tae a campaign against Poland an assured that Germany wad nae hae tae face the prospect o a twa-front war, as it haed in Warld War I. Immediately efter that, Hitler ordert the attack tae proceed on 26 August, but upon hearin that Breetain haed concludit a formal mutual assistance pact wi Poland, an that Italy wad mainteen neutrality, he decidit tae delay it.[42]

In response tae Breetish requests fur direct negotiations fur tae evit war, Germany made demands on Poland, that anerly served as a pretext tae worsen relations.[43] On 29 August, Hitler demanded that a Pols plenipotentiary immediately traivel fur tae Berlin tae negotiate the haundower o Danzig, an tae allou a plebiscite in the Pols Corridor in that the German minority wad vote on secession.[43] The Poles refuised tae complee wi the German demands, an on the nicht o 30–31 August in a veeolent meetin wi the Breetish ambassador Neville Henderson, Ribbentrop declared that Germany conseedert its claims rejectit.[44]

Coorse o the war

[eedit | eedit soorce]War braks oot in Europe (1939–40)

[eedit | eedit soorce]

On 1 September 1939, upon haein staged several mairch incidents, Germany invadit Poland. [45] The Battle o Westerplatte is aften descrived as the first European battle o Warld War II. Breetain respondit wi an ultimatum tae Germany tae cease militar operations, an on 3 September, efter the ultimatum wis ignored, Fraunce, Breetain, Australie, an New Zealand declared a war on Germany. This alliance wis jynt bi Sooth Africae (6 September) an Canadae (10 September). The alliance providit na direct militar support tae Poland, ootside o a cautious French probe intae the Saarland.[46] The Wastren Allies forby begoud a naval blockade o Germany, that aimed tae damage the kintra's economy an war effort.[47] Germany respondit bi orderin U-boat warfare agin Allied merchand an warships, that wad later escalate intae the Battle o the Atlantic.

On 8 September, German truips reached suburbs o Warsaw. The Pols wastlin coonter offensive hautit the German advance fur several day, but it wis ootflankit an encircled bi the Wehrmacht. Remnants o the Pols airmy brak throu tae besieged Warsaw. On 17 September 1939, efter signin a cease-fire wi Japan, the Soviets invadit Eastren Poland.[48]

On 27 September, Warsaw gairison signed a cease-fire an surrendered tae the Germans, an the last lairge operational unit o the Pols Airmy surrendered on 6 October. Maugre a militar defeat, the Pols govrenment niver surrendered; the Pols resistance established an Unnergrund State an a pairtisan Hame Airmy.[49].

Germany annexed the wastren an occupied the central pairt o Poland, an the USSR annexed its eastren pairt; smaw shares o Pols territory war transferred tae Lithuanie an Slovakie. On the 6t October, Hitler made a public peace owertur tae Breetain an Fraunce, but said that the futur o Poland wis tae be determined exclusively bi Germany an the Soviet Union. The proposal wis rejectit[44], an Hitler ordered an immediate offensive agin Fraunce,[50] that wad be postponed till the ware o 1940 due tae bad wather. [51][52][53]

The Soviet Union forced the Baltic kintras—Estonie, Latvie an Lithuanie, the states that war in a Soviet sphere o influence"—tae sign "mutual assistance pacts" that stipulatit stationin Soviet truips in thir kintras. Suin efter that, signeeficant Soviet militar contingent wis muived thare.[54][55][56]. Finland refuised tae sign a seemilar pact an rejectit tae cede pairt o its territory tae the USSR, thar promptit a Soviet invasion in November 1939[57], an the USSR wis expelt frae the League o Naitions[58]. Despite owerwhelmin numerical superiority, Soviet militar sonse wis modest, an the Finno-Soviet war endit in Mairch 1940 wi meenimal Finnish concessions.[59]

In Juin 1940, the Soviet Union forcibly annexed Estonie, Latvie an Lithuanie,[55] an the disputit Romanie regions o Bessarabie, Northren Bukovina an Hertza. Meanwhile, Nazi-Soviet poleetical rapprochement an economic co-operation[60][61] gradually stawed,[62][63] an baith states begoud preparations for war.[64]

Wastren Europe (1940–41)

[eedit | eedit soorce]

In Apryle 1940, Germany invadit Denmark an Norawa tae pertect shipments o airn ore frae Swaden, that the Allies war attemptin tae cut aff bi unilaterally minin neutral Norse watters.[65] Denmark capitulatit efter a few oors, an mauggre Allied support, in that the important herbour o Narvik temporarily wis recapturt frae the Germans, Norawa wis conquert within twa month.[66] Breetish discontent ower the Norse campaign led tae the replacement o the Breetish Prime Meenister, Neville Chamberlain, wi Winston Churchill on 10 Mey 1940.[67]

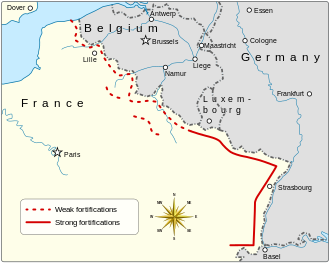

Germany launcht an offensive agin Fraunce an, adherin tae the Manstein Plan forby attackit the neutral naitions o Belgium, the Netherlands, an Luxembourg on 10 Mey 1940.[68] That same day, Breetish forces laundit in Iceland an the Faroes tae preempt a possible German invasion o the islands.[69] The US, in close co-operation wi the Dens envoy tae Washington D.C., greed tae pertect Greenland, layin the poleetical framewark for the formal establishment o bases in Apryle 1941. The Netherlands an Belgium wis owerrun uisin blitzkrieg tactics in a few days an weeks, respectively.[70] The French-fortifee'd Maginot Line an the main bouk o the Allied forces that haed muived intae Belgium wae circumventit bi a flankin muivement throu the thickly widdit Ardennes region,[71] mistakenly perceived bi Allied planners as an impenetrable naitural barrier against airmoured vehicles.[72][73] As a result, the bouk o the Allied airmies foond themsels trappit in an encirclement an war beaten. The majority war takken prisoner, whilst ower 300,000, maistly Breetish an French, war evacuated frae the continent at Dunkirk bi early Juin, awtho abandonin awmaist aw o thair equipment.[74]

On the 10t Juin, Italy invadit Fraunce, declarin war on baith Fraunce an the Unitit Kinrick.[75] Paris fell tae the Germans on the 14t Juin an aicht days later Fraunce signed an airmistice wi Germany an wis suin dividit intae German an Italian occupation zones,[76] an a wanoccupied rump state unner the Vichy Regime, that, tho offeecially neutral, wis generally aligned wi Germany. Fraunce kept its fleet but the Breetish feared the Germans wad seize it, sae on 3 Julie, the Breetish attacked it.[77]

The Battle o Breetain[78] begoud in early Julie wi Luftwaffe attacks on shippin an herbours.[79] On 19 Julie, Hitler again publicly offert tae end the war, sayin he wisna wantin tae destroy the Breetish Empire. The Unitit Kinrick rejectit this ultimatum.[80] The main German air superiority campaign stairtit in August but failed tae defeat RAF Fechter Command, an a proponed invasion wis postponed indefinitely on 17 September. The German strategic bombin offensive intensifee'd as nicht attacks on Lunnon an ither ceeties in the Blitz, but lairgely failed tae disrupt the Breetish war effort.[79]

Uisin newly capturt French ports, the German Navy enjoyed success against an ower-extendit Ryal Navy, uisin U-boats agin Breetish shippin in the Atlantic.[81] The Breetish scored a signeeficant veectory on 27 Mey 1941 bi sinkin the German battleship Bismarck.[82] Aiblins maist importantly, in the Battle o Breetain the Ryal Air Force haed successfully reseestit the Luftwaffe's assault, an the German bombin campaign lairgely endit in Mey 1941.[83]

Ootthrou this period, the neutral Unitit States teuk meisurs tae assist Cheenae an the Wastren Allies. In November 1939, the American Neutrality Act wis amendit tae allou "cash an cairy" purchases bi the Allies.[84] In 1940, follaein the German captur o Paris, the size o the Unitit States Navy wis signeeficantly increased. In September, the Unitit States forder greed tae a tred o American destroyers for Breetish bases.[85] Still, a lairge majority o the American public conteena'd tae oppone ony direct militar intervention intae the conflict weel inte 1941.[86] Awtho Roosevelt haed promised tae keep the Unitit States oot o the war, he nivertheless teuk concrete steps tae prepare for war.

At the end o September 1940, the Tripartite Pact unitit Japan, Italy an Germany tae formalise the Axis Pouers. The Tripartite Pact stipulatit that ony kintra, wi the exception o the Soviet Union, no in the war that attacked ony Axis Power wad be forced tae gae tae war agin aw three.[87] The Axis expandit in November 1940 whan Hungary, Slovakie an Romanie jynt the Tripartite Pact.[88] Romanie wad mak a major contreibution (as did Hungary) tae the Axis war agin the USSR, pairtially tae recaptur territory cedit tae the USSR, pairtially tae pursue its leader Ion Antonescu's desire tae combat communism.[89]

Mediterranean (1940–41)

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Italy begoud operations in the Mediterranean, ineetiatin a siege o Maltae in Juin, conquerin Breetish Somaliland in August, an makkin an incursion intae Breetish-held Egyp in September 1940. In October 1940, Italy stairtit the Greco-Italian War acause o Mussolini's jealousy o Hitler's success but within days wis repulsed wi few territorial gains an a stalemate suin occurred.[90] The Unitit Kinrick respondit tae Greek requests for assistance bi sendin truips tae Crete an providin air support tae Greece. Hitler decidit that whan the wather impruived he wad tak action against Greece tae assist the Italians an prevent the Breetish frae gaining a fithauld in the Balkans, tae strike against the Breetish naval dominance o the Mediterranean, an tae siccar his hauld on Romanie ile.[91]

Bi late Mairch 1941, follaein Bulgarie's signin o the Tripartite Pact, the Germans war in poseetion tae intervene in Greece. Plans chynged, houiver, acause o developments in neighbourin Yugoslavie. The Yugoslav govrenment haed signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 Mairch, anerly tae be owerthrawn twa day efter bi a Breetish-encouraged coup. Hitler viewed the new regime as hostile an immediately decidit tae eliminate it. On 6 Apryle Germany simultaneously invadit baith Yugoslavie an Greece, makkin rapid progress an forcin baith naitions tae surrender within the month. The Breetish war driven frae the Balkans efter Germany conquered the Greek island o Crete bi the end o Mey.[92] Awtho the Axis veectory wis swift, bitter pairtisan warfare subsequently brak oot agin the Axis occupation o Yugoslavie, whilk conteena'd till the end o the war.

Axis attack on the USSR (1941)

[eedit | eedit soorce]Wi the situation in Europe an Asie relatively stable, Germany, Japan, an the Soviet Union made preparations. Wi the Soviets waurie o moontin tensions wi Germany an the Japanese plannin tae tak advantage o the European War bi seizin resoorce-rich European possessions in Sootheast Asie, the twa pouers signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact in Apryle 1941.[93] Bi contrast, the Germans war steadily makkin preparations for an attack on the Soviet Union, massin forces on the Soviet mairch.[94]

Hitler believed that Breetain's refuisal tae end the war wis based on the howp that the Unitit States an the Soviet Union wad enter the war agin Germany suiner or later.[95] He tharefore decidit tae try tae strenthen Germany's relations wi the Soviets, or failin that, tae attack an eliminate them as a factor. In November 1940, negotiations teuk place tae determine if the Soviet Union wad jyne the Tripartite Pact. The Soviets shawed some interest, but asked for concessions frae Finland, Bulgarie, Turkey, an Japan that Germany conseedert unacceptable. On 18 December 1940, Hitler issued the directive tae prepare for an invasion o the Soviet Union.

On 22 Juin 1941, Germany, supportit bi Italy an Romanie, invadit the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa, wi Germany accusin the Soviets o plottin agin them. Thay war jynt shortly bi Finland an Hungary.[96] The primar targets o this surprise offensive[97][page needit] war the Baltic region, Moscow an Ukraine, wi the ultimate goal o endin the 1941 campaign near the Arkhangelsk-Astrakhan line, frae the Caspian tae the White Seas. Hitler's objectives war tae eliminate the Soviet Union as a militar pouer, exterminate Communism, generate Lebensraum ("leevin space")[98] bi dispossessin the native population[99][page needit] an guarantee access tae the strategic resoorces needit tae defeat Germany's remeenin rivals.[100][page needit]

Awtho the Reid Airmy wis preparin for strategic coonter-offensives afore the war,[101][page needit] Barbarossa forced the Soviet supreme command tae adopt a strategic defence. In the simmer, the Axis made signeeficant gains intae Soviet territory, inflictin immense losses in baith personnel an materiel. By the middle o August, houiver, the German Airmy Heich Command decidit tae suspend the offensive o a conseederably depletit Airmy Group Centre, an tae divert the 2nt Panzer Group tae reinforce truips advancin taewart central Ukraine an Leningrad.[102][page needit] The Kiev offensive wis owerwhalminly successfu, resultin in encirclement an elimination o fower Soviet airmies, an made possible further advance intae Crimea an industrially developit Eastren Ukraine (the First Battle o Kharkov).[103]

The diversion o three quarter o the Axis truips an the majority o thair air forces frae Fraunce an the central Mediterranean tae the Eastren Front[104] promptit Breetain tae reconseeder its grand strategy.[105][page needit] In Julie, the UK an the Soviet Union formed a militar alliance against Germany[106] The Breetish an Soviets invadit neutral Iran tae siccar the Persian Corridor an Iran's ile fields.[107] In August, the Unitit Kinrick an the Unitit States jyntly issued the Atlantic Chairter.[108]

Bi October Axis operational objectives in Ukraine an the Baltic region war achieved, wi anerly the sieges o Leningrad[109][page needit] an Sevastopol conteenain.[110] A major offensive against Moscow wis renewed; efter twa month o fierce battles in increasinly hersh wather the German airmy awmaist reached the ooter suburbs o Moscow, whaur the exhaustit truips[111] war forced tae suspend thair offensive.[112] Lairge territorial gains war made bi Axis forces, but thair campaign haed failed tae achieve its main objectives: twa key ceeties remeened in Soviet haunds, the Soviet capability tae resist wis nae brak, an the Soviet Union reteened a conseederable pairt o its militar potential. The blitzkrieg phase o the war in Europe haed endit.[113][page needit]

Bi early December, freshly mobilised reserves[114][page needit] alloued the Soviets tae achieve numerical parity wi Axis truips.[115] This, as weel as intelligence data that established that a meenimal nummer o Soviet truips in the East wad be sufficient tae deter ony attack bi the Japanese Kwantung Airmy,[116][page needit] alloued the Soviets tae begin a massive coonter-offensive that stairtit on 5 December aw alang the front an pushed German truips 100–250 kilometre (62–155 mi) wast.[117]

War braks out in the Paceefic (1941)

[eedit | eedit soorce]In 1939, the Unitit States haed renoonced its tred treaty wi Japan; an, beginnin wi an aviation petrol ban in Julie 1940, Japan becam subject tae increasin economic pressur.[80] In this time, Japan launched its first attack against Changsha, a strategically important Cheenese ceety, but wis repulsed bi late September.[118] Despite several offensives bi baith sides, the war atween Cheenae an Japan wis stalematit bi 1940. Tae increase pressur on Cheenae bi blockin supply routes, an tae better poseetion Japanese forces in the event o a war wi the Wastren powers, Japan invadit an occupied northren Indocheenae.[119] Efterwart, the Unitit States embargoed airn, steel an mechanical pairts against Japan.[120] Ither sanctions suin follaed.

Syne early 1941 the Unitit States an Japan haed been engaged in negotiations in an attempt tae impruive thair streened relations an end the war in Cheenae. In thir negotiations Japan advanced a nummer o proponements that war dismissed bi the Americans as inadequate.[121] At the same time the US, Breetain, an the Netherlands engaged in saicret discussions for the jynt defence o thair territories, in the event o a Japanese attack against ony o them.[122] Roosevelt reinforced the Philippines (an American pertectorate scheduled for unthirldom in 1946) an wairned Japan that the US wad react tae Japanese attacks against ony "neebourin kintra".[122] Japan prepared for war efter failed negotiations.

On 7 December 1941 (8 December in Asie time zones), Japan attacked Breetish an American hauldins wi near-simultaneous offensives against Sootheast Asie an the Central Paceefic.[123] Thir includit an attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, landings in Thailand an Malaya[123] an the battle o Hong Kong. Thir attacks led the Unitit States, Unitit Kinrick, Cheenae, Australie an several ither states tae formally declare war on Japan, whauras the Soviet Union, bein hivily involved in lairge-scale hostilities wi European Axis kintras, mainteened its neutrality agreement wi Japan.[124] Germany, follaed bi the ither Axis states, declared war on the Unitit States[125] in solidarity wi Japan, citin as juistification the American attacks on German war veshels that haed been ordered bi Roosevelt.[96][126]

Axis advance staws (1942–43)

[eedit | eedit soorce]In 1942, Allied offeecials debatit on the appropriate grand strategy tae pursue. Aw agreed that defeatin Germany wis the primar objective. The Americans favourt a straichtforrit, lairge-scale attack on Germany throu Fraunce. The Soviets wis forby demandin a seicont front. The Breetish, on the ither haund, argied that militar operations shoud target peripheral auries tae weir oot German strenth, leadin tae increasin demoralisation, an bolster resistance forces. Germany itsel wad be subject tae a hivy bombin campaign. An offensive agin Germany wad then be launched primarily bi Allied airmour withoot uisin lairge-scale airmies.[127] Eventually, the Breetish persuadit the Americans that a laundingin Fraunce wis infeasible in 1942 an thay shoud insteid focus on drivin the Axis oot o North Africae.[128]

Paceefic (1942–43)

[eedit | eedit soorce]Bi the end o Apryle 1942, Japan an its ally Thailand haed awmaist fully conquered Burma, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, an Rabaul, inflictin severe losses on Allied truips an takkin a lairge nummer o preesoners.[129] Despite stubborn resistance bi Filipino an US forces, the Philippine Commonweel wis eventually capturt in Mey 1942, forcin its govrenment intae exile.[130]

In airly Mey 1942, Japan ineetiatit operations tae captur Port Moresby bi amphibious assault an sicweys sever communications an supply lines atween the Unitit States an Australie. The plant invasion wis thortert whan an Allied task force, centred on twa American fleet cairiers, focht Japanese naval forces tae a draw in the Battle o the Coral Sea.[131] Japan's next plan, motivatit bi the earlier Doolittle Raid, wis tae seize Midway Atoll an wyse American cairiers intae battle tae be eliminatit; as a diversion, Japan wad forby send forces tae occupy the Aleutian Islands in Alaska.[132] In mid-Mey, Japan stairtit the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Campaign in Cheenae, wi the goal o inflictin retribution on the Cheenese that aidit the survivin American airmen in the Doolittle Raid bi destroyin air bases an fechtin against the Cheenese 23rd an 32nd Airmy Groups.[133][134] In early Juin, Japan put its operations intae action but the Americans, haein brak Japanese naval codes in late Mey, war fully awaur o plans an order o battle, an uised this knawledge tae achieve a decisive veectory at Midway ower the Imperial Japanese Navy.[135]

Eastren Front (1942–43)

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Maugre conseederable losses, in airly 1942 Germany an its allies stappit a major Soviet offensive in central an soothren Roushie, keepin maist territorial gains thay haed achieved in the umwhile year.[136]

Bi mid-November, the Germans haed nearly takken Stalingrad in bitter street fechtin whan the Soviets begoud thair seicont winter coonter-offensive, stairtin wi an encirclement o German forces at Stalingrad[137] an an assault on the Rzhev salient near Moscow, tho the latter failed disastrously.[138] Bi early Februar 1943, the German Airmy haed taen tremendous losses; German truips at Stalingrad haed been forced tae surrender,[139] an the front-line haed been pushed back ayont its poseetion afore the simmer offensive. In mid-Februar, efter the Soviet push haed tapered aff, the Germans launcht anither attack on Kharkov, creautin a salient in thair front line aroond the Soviet ceety o Kursk.[140]

Wastren Europe/Atlantic an Mediterranean (1942–43)

[eedit | eedit soorce]Exploitin puir American naval command deceesions, the German navy ravaged Allied shippin aff the American Atlantic coast.[141] Bi November 1941, Commonweel forces haed launched a coonter-offensive, Operation Crusader, in North Africae, an reclaimed aw the gains the Germans an Italians haed made.[142]

In Juin 1943 the Breetish an Americans begoud a strategic bombin campaign against Germany wi a goal tae disrupt the war economy, reduce morale, an "de-hoose" the ceevilian population.[143] The firebombin o Hamburg wis amang the first attacks in this campaign, it lead tae signeeficant causalities an inflictit conseederable losses on infrastructur o this important industrial centre.[144]

Allies gain momentum (1943–44)

[eedit | eedit soorce]On 3 September 1943, the Wastren Allies invadit the Italian mainland, follaein Italy's airmistice wi the Allies.[145] Germany wi the help o fascists respondit bi disairmin Italian forces that wis in mony places withoot superior orders, seizin militar control o Italian auries,[146] an creautin a series o defensive lines.[147] German special forces then rescued Mussolini, that then suin established a new client state in German-occupied Italy named the Italian Social Republic,[148] causin an Italian ceevil war. The Wastren Allies focht throu several lines till reachin the main German defensive line in mid-November.[149]

In November 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt an Winston Churchill met wi Chiang Kai-shek in Cairo an then wi Joseph Stalin in Tehran.[150] The umwhile conference determined the post-war return o Japanese territory[151] an the militar plannin fur the Burma Campaign,[152] while the latter includit greement that the Wastren Allies wad invade Europe in 1944 an that the Soviet Union wad declare war on Japan within three month o Germany's defeat.[153]

Bi the end o Januar 1944, a major Soviet offensive herried oot German forces frae the Leningrad region,[154] endin the langest an maist lethal siege in history. Bi late Mey, the Soviets haed leeberatit Crimea, lairgely expelled Axis forces frae Ukraine, an made incursions intae Romanie, that war repulsed bi the Axis truips.[155] The Allied offensives in Italy haed succeedit an, at the expense o allouin several German diveesions tae retreat, on 4 Juin, Roum wis capturt.[156]

Allies close in (1944)

[eedit | eedit soorce]

On 6 Juin 1944 (kent as D-Day), efter three year o Soviet pressur,[157] the Wastren Allies invadit northren Fraunce. Efter reassignin several Allied divisions frae Italy, thay forby attacked soothren Fraunce.[158] Thir laundins war successfu, an led tae the defeat o the German Airmy units in Fraunce. Paris wis leeberatit bi the local reseestance assistit bi the Free French Forces, baith led bi General Charles de Gaulle, on 25 August[159] an the Wastren Allies conteena'd tae push back German forces in wastren Europe in the latter pairt o the year. An attempt tae advance intae northren Germany speirheidit bi a major airborne operation in the Netherlands failed.[160] Thareefter, the Wastren Allies slawly pushed intae Germany, but failed tae cross the Ruhr river in a lairge offensive. In Italy, Allied advance forby slawed due tae the last major German defensive line.[161]

On 22 Juin, the Soviets launched a strategic offensive in Belaroushie ("Operation Bagration") that destroyed the German Airmy Group Centre awmaist completely.[162] Suin efter that anither Soviet strategic offensive forced German truips frae Wastren Ukraine an Eastren Poland. The Soviet advance promptit reseestance forces in Poland tae ineetiate several uprisins agin the German occupation. Houiver, the lairgest o thir in Warsaw, whaur German sodgers massacred 200,000 ceevilians, an a naitional uprisin in Slovakie, did nae receive Soviet support an war subsequently suppressed bi the Germans.[163] The Reid Airmy's strategic offensive in eastren Romanie cut aff an destroyed the conseederable German truips thare an triggered a successfu coup d'état in Romanie an in Bulgarie, follaed bi thae kintras' shift tae the Allied side.[164]

In September 1944, Soviet truips advanced intae Yugoslavie an forced the rapid widrawal o German Airmy Groups E an F in Greece, Albanie an Yugoslavie tae rescue them frae bein cut aff.[165] Bi this pynt, the Communist-led Pairtisans unner Marshal Josip Broz Tito, that haed led an increasinly successfu guerrilla campaign against the occupation syne 1941, controlled muckle o the territory o Yugoslavie an engaged in delayin efforts against German forces forder sooth. In northren Serbie, the Reid Airmy, wi leemitit support frae Bulgarie forces, assisted the Pairtisans in a jynt leeberation o the caipital ceety o Belgrade on 20 October. A few days later, the Soviets launched a massive assault against German-occupied Hungary that lastit till the faw o Budapest in Februar 1945.[166] Unlik impressive Soviet veectories in the Balkans, bitter Finnish reseestance tae the Soviet offensive in the Karelie Isthmus denee'd the Soviets occupation o Finland an led tae a Soviet-Finnish airmistice on relatively mild condeetions,[167][168] awtho Finland wis forced tae fecht thair umwhile allies.

In the Paceefic, US forces conteena'd tae press back the Japanese perimeter. In mid-Juin 1944, thay begoud thair offensive agin the Mariana an Palau islands, an decisively defeatit Japanese forces in the Battle o the Philippine Sea. Thir defeats led tae the resignation o the Japanese Prime Meenister, Hideki Tojo, an providit the Unitit States wi air bases tae launch intensive hivy bomber attacks on the Japanese hame islands. In late October, American forces invadit the Filipino island o Leyte; suin efter, Allied naval forces scored anither lairge veectory in the Battle o Leyte Gulf, ane o the lairgest naval battles in history.[169]

Axis collapse, Allied veectory (1944–45)

[eedit | eedit soorce]

On 16 December 1944, Germany made a last attempt on the Wastren Front bi uisin maist o its remeenin reserves tae launch a massive coonter-offensive in the Ardennes an alang the French–German mairch tae split the Wastren Allies, encircle lairge portions o Wastren Allied truips an captur thair primar supply port at Antwerp tae prompt a poleetical dounset.[170] Bi Januar, the offensive haed been repulsed wi na strategic objectives fulfilled.[170] In Italy, the Wastren Allies remeened stalemated at the German defensive line. In mid-Januar 1945, the Soviets an Poles attacked in Poland, pushin frae the Vistula tae the Oder river in Germany, an overran East Proushie.[171] On 4 Februar, Soviet, Breetish an US leaders met for the Yalta Conference. Thay greed on the occupation o post-war Germany, an on whan the Soviet Union wad jyne the war against Japan.[172]

In Februar, the Soviets entered Silesie an Pomeranie, while Wastren Allies entered wastren Germany an closed tae the Rhine river. Bi Mairch, the Wastren Allies crossed the Rhine north an sooth o the Ruhr, encirclin the German Airmy Group B,[173] while the Soviets advanced tae Vienna. In early Apryle, the Wastren Allies feenally pushed forrit in Italy an soopit athort wastren Germany capturin Hamburg an Nuremberg, while Soviet an Polshforces stormed Berlin in late Apryle. American an Soviet forces met at the Elbe river on 25 Apryle. On 30 Apryle 1945, the Reichstag wis capturt, seegnallin the militar defeat o Nazi Germany.[174]

Several chynges in leadership occurred in this period. On 12 Apryle, Preses Roosevelt dee'd an wis succeedit bi Harry S. Truman. Benito Mussolini wis killt bi Italian pairtisans on 28 Apryle.[175] Twa days later, Hitler committit suicide, an wis succeedit bi Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz.[176]

German forces surrendered in Italy on 29 Apryle. Tot an uncondeetional surrender wis signed on 7 Mey, tae be effective bi the end o 8 Mey.[177] German Airmy Group Centre reseestit in Prague till 11 Mey.[178]

In the Paceefic theatre, American forces accompanied bi the forces o the Philippine Commonweel advanced in the Philippines, clearin Leyte bi the end o Apryle 1945. Thay laundit on Luzon in Januar 1945 an recapturt Manila in Mairch follaein a battle that reduced the ceety tae ruins. Fechtin conteena'd on Luzon, Mindanao, an ither islands o the Philippines till the end o the war.[179] Meanwhile, the Unitit States Airmy Air Forces (USAAF) war destroyin strategic an populatit ceeties an touns in Japan in an effort tae destroy Japanese war industrie an ceevilian morale. On the nicht o 9–10 Mairch, USAAF B-29 bombers struck Tokyo wi thoosands o incendiary bombs, that killt 100,000 ceevilians an destroyed 16 square mile (41 km2) within a few oors. Ower the next five month, the USAAF firebombed a tot o 67 Japanese ceeties, killin 393,000 ceevilians an destroyin 65% o biggit-up auries.[180]

On 11 Julie, Allied leaders met in Potsdam, Germany. Thay confirmed earlier greements aboot Germany,[181] an reiteratit the demand for uncondeetional surrender o aw Japanese forces bi Japan, speceefically statin that "the alternative for Japan is prompt an utter destruction".[182] In this conference, the Unitit Kinrick held its general election, an Clement Attlee replaced Churchill as Prime Meenister.[183]

The Allies cried for uncondeetional Japanese surrender in the Potsdam Declaration o 27 Julie, but the Japanese govrenment rejectit the cry. In early August, the USAAF drappit atomic bombs on the Japanese ceeties o Hiroshima an Nagasaki. Atween the twa bombins, the Soviets, pursuant tae the Yalta greement, invadit Japanese-held Manchurie, an quickly defeatit the Kwantung Airmy, that wis the lairgest Japanese fechtin force.[184][185] The Reid Airmy an aw capturt Sakhalin Island an the Kuril Islands. On 15 August 1945, Japan surrendered, wi the surrender documents feenally signed at Tokyo Bay on the deck o the American battleship USS Missouri on 2 September 1945, endin the war.[186]

Eftermath

[eedit | eedit soorce]The Allies established occupation admeenistrations in Austrick an Germany. The umwhile becam a neutral state, non-aligned wi ony poleetical bloc. The latter wis dividit intae wastren an eastren occupation zones controlled bi the Wastren Allies an the USSR, accordinly. A denazification programme in Germany led tae the prosecution o Nazi war criminals an the remuival o ex-Nazis frae power, awtho this policy muived taewart amnesty an re-integration o ex-Nazis intae Wast German society.[187]

In an effort tae mainteen warld peace,[188] the Allies formed the Unitit Naitions, that offeecially cam intae exeestence on 24 October 1945,[189] an adoptit the Universal Declaration o Human Richts in 1948, as a common staundart for aw member naitions.[190]

Post-war diveesion o the warld wis formalised bi twa internaitional militar alliances, the Unitit States-led NATO an the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact;[191] the lang period o poleetical tensions an militar competeetion atween them, the Cauld War, wad be accompanied bi an unprecedentit airms race an proxy wars.[192]

Korea, umwhile unner Japanese rule, wis dividit an occupied bi the Soviet Union in the North an the US in the Sooth atween 1945 an 1948. Separate republics emerged on baith sides o the 38t parallel in 1948, ilk claimin tae be the legitimate govrenment for aw o Korea, that led ultimately tae the Korean War.[193]

In Cheenae, naitionalist an communist forces resumed the ceevil war in Juin 1946. Communist forces war veectorious an established the Fowkrepublic o Cheenae on the mainland, while naitionalist forces retreatit tae Taiwan in 1949.[194]

Impact

[eedit | eedit soorce]Casualties an war crimes

[eedit | eedit soorce]Estimates fur the tot nummer o casualties in the war varies, acause mony diaths went wanrecordit. Maist suggests that some 60 million fowk dee'd in the war, includin aboot 20 million militar personnel an 40 million ceevilians.[195][196][197] Mony o the ceevilians dee'd acause o deliberate genocide, massacres, mass-bombins, disease, an stairvation.

In Asie an the Paceefic, atween 3 million an mair nor 10 million ceevilians, maistly Cheenese (estimatit at 7.5 million[198]), wis killt bi the Japanese occupation forces.[199] The best-kent Japanese atrocity wis the Nanking Massacre, in that fifty tae three hunder thoosand Cheenese ceevilians war raped an murthert.[200] Mitsuyoshi Himeta reportit that 2.7 million casualties occurred in the Sankō Sakusen. General Yasuji Okamura implementit the policy in Heipei an Shantung.[201]

The Soviet Union wis responsible for the Katyn massacre o 22,000 Pols officers,[202] an the impreesonment or execution o thoosands o poleetical preesoners bi the NKVD,[203]

Genocide an concentration camps

[eedit | eedit soorce]The German govrenment led bi Adolf Hitler an the Nazi Pairty wis responsible for the Holocaust (killin o thareaboot 6 million Jews), as weel as fur killin o 2.7 million ethnic Poles,[204] an 4 million ithers that war deemed "unworthy o life" (includin the disabled an mentally ill, Soviet preesoners o war, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah's Witnesses, an Romani) as pairt o a programme o deliberate extermination. Soviet POWs wis kept in especially unbeirable condeetion, an, awtho thair extermination wisnae an offeecial goal, 3.6 million o Soviet POWs oot o 5.7 dee'd in Nazi camps in the war.[205][206] In addeetion tae concentration camps, daith camps wis creatit in Nazi Germany fur tae exterminate fowk at an industrial scale.

Notes

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ 23 August 1939, the USSR an Germany sign non-aggression pact, secretly dividin Eastren Europe intae spheres o influence. USSR armistice wi Japan 16 September 1939; invades Poland 17 September 1939; attacks Finland 30 September 1939; forcibly incorporates Baltic States Juin 1940; takes eastren Romanie 4 Julie 1940. 22 Juin 1941, USSR is invaded bi European Axis; USSR aligns wi kintras fichtin Axis.

- ↑ Efter the fall o the Third Republic in 1940, the de facto govrenment wis the Vichy Regime. It conductit pro-Axis policies till November 1942 while remainin formally neutral. The Free French Forces, based oot o Lunnon, wur recognized bi aw Allies as the offeecial govrenment in September 1944.

Citations

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ Fitzgerald 2011, p. 4

- ↑ Hedgepeth & Saidel 2010, p. 16

- ↑ James A. Tyner (3 Mairch 2009). War, Violence, and Population: Making the Body Count. The Guilford Press; 1 edition. p. 49. ISBN 1-6062-3038-7.

- ↑ Sommerville 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Barrett & Shyu 2001, p. 6.

- ↑ Axelrod, Alan (2007) Encyclopedia of World War II, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 659.

- ↑ The UN Security Council, archived frae the original on 20 Juin 2012, retrieved 15 Mey 2012

- ↑ Herman Van Rompuy, President of the European Council; José Manuel Durão Barroso, President of the European Commission (10 December 2012). "From War to Peace: A European Tale". Nobel Lecture by the European Union. Retrieved 4 Januar 2014.

- ↑ Ingram 2006, pp. 76–8.

- ↑ Kantowicz 1999, p. 149.

- ↑ Shaw 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Brody 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ Zalampas 1989, p. 62.

- ↑ Adamthwaite 1992, p. 52.

- ↑ Preston 1998, p. 104.

- ↑ Myers & Peattie 1987, p. 458.

- ↑ Smith & Steadman 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Coogan 1993: "Although some Chinese troops in the Northeast managed to retreat south, others were trapped by the advancing Japanese Army and were faced with the choice of resistance in defiance of orders, or surrender. A few commanders submitted, receiving high office in the puppet government, but others took up arms against the invader. The forces they commanded were the first of the volunteer armies."

- ↑ Busky 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ Payne 2008, p. 271.

- ↑ Payne 2008, p. 146.

- ↑ Eastman 1986, pp. 547–51.

- ↑ a b Guo 2005

- ↑ a b Hsu & Chang 1971, pp. 195–200.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). "A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East". ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 27 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Yang Kuisong, "On the reconstruction of the facts of the Battle of Pingxingguan"

- ↑ Levene, Mark and Roberts, Penny. The Massacre in History. 1999, page 223-4

- ↑ Totten, Samuel. Dictionary of Genocide. 2008, 298–9.

- ↑ Hsu & Chang 1971, pp. 221–230.

- ↑ Eastman 1986, p. 566.

- ↑ Taylor 2009, pp. 150–2.

- ↑ Sella 1983, pp. 651–87.

- ↑ Collier & Pedley 2000, p. 144.

- ↑ Kershaw 2001, pp. 121–2.

- ↑ Kershaw 2001, p. 157.

- ↑ Davies 2006, pp. 143–4 (2008 ed.).

- ↑ Lowe & Marzari 2002, p. 330.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 234.

- ↑ Derek Watson, Molotov's Apprenticeship in Foreign Policy: The Triple Alliance Negotiations in 1939, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Jun., 2000), pp. 695-722 [1]

- ↑ Shore 2003, p. 108.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 608.

- ↑ "The German Campaign In Poland (1939)". Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ a b "The Danzig Crisis". ww2db.com.

- ↑ a b "Major international events of 1939, with explanation". Ibiblio.org.

- ↑ Evans 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Keegan 1997, p. 35.

Cienciala 2010, p. 128, observes that, while it is true that Poland wis faur awey, makkin it difficult for the French an Breetish tae provide support, "[f]ew Western historians of World War II ... know that the British had committed to bomb Germany if it attacked Poland, but did not do so except for one raid on the base of Wilhelmshafen. The French, who committed to attack Germany in the west, had no intention of doing so." - ↑ Beevor 2012, p. 32; Dear & Foot 2001, pp. 248–9; Roskill 1954, p. 64.

- ↑ Zaloga 2002, pp. 80, 83.

- ↑ Hempel 2005, p. 24.

- ↑ Nuremberg Documents C-62/GB86, a directive frae Hitler in October 1939 whilk concludes: "The attack [on France] is tae be launcht this Autumn if conditions is possible ava."

- ↑ Liddell Hart 1977, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Bullock 1990, pp. 563–4, 566, 568–9, 574–5 (1983 ed.).

- ↑ Blitzkrieg: From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk, L Deighton, Jonathan Cape, 1993, p186-7. Deighton states that "the offensive was postponed twenty-nine times before it finally took place."

- ↑ Smith et al. 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ a b Bilinsky 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ Murray & Millett 2001, pp. 55–6.

- ↑ Spring 1986, p. 207-226.

- ↑ Carl van Dyke. The Soviet Invasion of Finland. Frank Cass Publishers, Lindon, Portland, OR. ISBN 0-7146-4753-5, p. 71.

- ↑ Hanhimäki 1997, p. 12.

- ↑ Ferguson 2006, pp. 367, 376, 379, 417.

- ↑ Snyder 2010, p. 118ff.

- ↑ Koch 1983.

- ↑ Roberts 2006, p. 56.

- ↑ Roberts 2006, p. 59.

- ↑ Murray & Millett 2001, pp. 57–63.

- ↑ Commager 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ Reynolds 2006, p. 76.

- ↑ Evans 2008, pp. 122–3.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 436. The Americans later relieved the Breetish, wi marines arrivin in Reykjavik on 7 Julie 1941 (Schofield 1981, p. 122).

- ↑ Shirer 1990, pp. 721–3.

- ↑ Keegan 1997, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Regan 2004, p. 152.

- ↑ Liddell Hart 1977, p. 48.

- ↑ Keegan 1997, pp. 66–7.

- ↑ Overy & Wheatcroft 1999, p. 207.

- ↑ Umbreit 1991, p. 311.

- ↑ Brown 2004, p. xxx.

- ↑ Keegan 1997, p. 72.

- ↑ a b Murray 1983, The Battle of Britain.

- ↑ a b "Major international events of 1940, with explanation". Ibiblio.org.

- ↑ Goldstein 2004, p. 35. Aircraft played a heichly important role in defeatin the German U-boats (Schofield 1981, p. 122).

- ↑ Steury 1987, p. 209; Zetterling & Tamelander 2009, p. 282.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, pp. 108–9.

- ↑ Overy & Wheatcroft 1999, pp. 328–30.

- ↑ Maingot 1994, p. 52.

- ↑ Cantril 1940, p. 390.

- ↑ Bilhartz & Elliott 2007, p. 179.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 877.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, pp. 745–6.

- ↑ Clogg 2002, p. 118.

- ↑ Evans 2008, pp. 146, 152; US Army 1986, pp. 4–6

- ↑ Weinberg 2005, p. 229.

- ↑ Garver 1988, p. 114.

- ↑ Weinberg 2005, p. 195.

- ↑ Murray 1983, p. 69.

- ↑ a b Klooz, Marle; Wiley, Evelyn (1944), Events leading up to World War II – Chronological History, 78th Congress, 2d Session – House Document N. 541, Director: Humphrey, Richard A., Washington: US Government Printing Office, pp. 267–312 (1941).

- ↑ Sella 1978.

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, pp. 66–9.

- ↑ Steinberg 1995.

- ↑ Hauner 1978.

- ↑ Roberts 1995.

- ↑ Wilt 1981.

- ↑ Erickson 2003, pp. 114–37.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 9.

- ↑ Farrell 1993.

- ↑ Keeble 1990, p. 29.

- ↑ Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003, p. 425.

- ↑ Beevor 2012, p. 220.

- ↑ Kleinfeld 1983.

- ↑ Jukes 2001, p. 113.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 26: "By 1 November [the Wehrmacht] had lost fully 20% of its committed strength (686,000 men), up to 2/3 of its ½-million motor vehicles, and 65 percent of its tanks. The German Army High Command (OKH) rated its 136 divisions as equivalent to 83 full-strength divisions."

- ↑ Reinhardt 1992, p. 227.

- ↑ Milward 1964.

- ↑ Rotundo 1986.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 26.

- ↑ Garthoff 1969.

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 41–2; Evans 2008, pp. 213–4, notes that "Zhukov had pushed the Germans back where they had launched Operation Typhoon two months before. ... Only Stalin's decision to attack all along the front instead of concentrating his forces in an all-out assault against the retreating German Army Group Centre prevented the disaster from being even worse."

- ↑ Jowett & Andrew 2002, p. 14.

- ↑ Overy & Wheatcroft 1999, p. 289.

- ↑ Morison 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ "The decision for War". US Army in WWII – Strategy and Command: The First Two Years. pp. 113–27.

- ↑ a b "The Showdown With Japan Aug–Dec 1941". US Army in WWII – Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare. pp. 63–96.

- ↑ a b Wohlstetter 1962, pp. 341–3.

- ↑ Dunn 1998, p. 157. According to May 1955, p. 155, Churchill stated: "Russian declaration of war on Japan would be greatly to our advantage, provided, but only provided, that Russians are confident that will not impair their Western Front."

- ↑ Adolf Hitler's Declaration of War against the United States in Wikisource.

- ↑ Klooz, Marle; Wiley, Evelyn (1944), Events leading up to World War II – Chronological History, 78th Congress, 2d Session – House Document N. 541, Director: Humphrey, Richard A., Washington: US Government Printing Office, p. 310 (1941).

- ↑ "The First Full Dress Debate over Strategic Deployment. Dec 1941 – Jan 1942". US Army in WWII – Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare. pp. 97–119.

- ↑ "The Elimination of the Alternatives. Jul–Aug 1942". US Army in WWII – Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare. pp. 266–92.

- ↑ Beevor 2012, pp. 247–267, 345.

- ↑ Lewis 1953, p. 529 (Table 11).

- ↑ Maddox 1992, pp. 111–2.

- ↑ Salecker 2001, p. 186.

- ↑ Schoppa 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ Chevrier & Chomiczewski & Garrigue 2004, p.19.

- ↑ Ropp 2000, p. 368.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 239–65.

- ↑ Black 2003, p. 119.

- ↑ Beevor 1998, pp. 383–91.

- ↑ Erickson 2001, p. 142.

- ↑ Milner 1990, p. 52.

- ↑ Beevor 2012, pp. 224–8.

- ↑ "The Civilians" United States Strategic Bombing Survey Summary Report (European War)

- ↑ Overy 1995, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Kolko 1990, p. 45

- ↑ Mazower 2008, p. 362.

- ↑ Hart, Hart & Hughes 2000, p. 151.

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2006, p. 52.

- ↑ Read & Fisher 2002, p. 129.

- ↑ Kolko 1990, pp. 211, 235, 267–8.

- ↑ Iriye 1981, p. 154.

- ↑ Mitter 2014, p. 286.

- ↑ Polley 2000, p. 148.

- ↑ Glantz 2002, pp. 327–66.

- ↑ Chubarov 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ Holland 2008, pp. 169–84; Beevor 2012, pp. 568–73.

The weeks after the fall of Rome saw a dramatic upswing in German atrocities in Italy (Mazower 2008, pp. 500–2). The period featurt massacres wi victims in the hundrers at Civitella (de Grazia & Paggi 1991; Belco 2010), Fosse Ardeatine (Portelli 2003), an Sant'Anna di Stazzema (Gordon 2012, pp. 10–1), an is kaipit wi the Marzabotto massacre. - ↑ Rees 2008, pp. 406–7: "Stalin always believed that Britain and America were delaying the second front so that the Soviet Union would bear the brunt of the war."

- ↑ Weinberg 2005, p. 695.

- ↑ Badsey 1990, p. 91.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 562.

- ↑ Forrest, Evans & Gibbons 2012, p. 191

- ↑ Zaloga 1996, p. 7: "It was the most calamitous defeat of all the German armed forces in World War II."

- ↑ Berend 1996, p. 8.

- ↑ "Armistice Negotiations and Soviet Occupation". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

The coup speeded the Red Army's advance, and the Soviet Union later awarded Michael the Order of Victory for his personal courage in overthrowing Antonescu and putting an end to Romania's war agin the Allies. Western historians uniformly point out that the Communists jist played a uphaudin role in the coup; efter-war Romanian historians, housomeir, ascribe tae the Communists the decisive role in Antonescu's overthrow

- ↑ Evans 2008, p. 653.

- ↑ Wiest & Barbier 2002, pp. 65–6.

- ↑ Wiktor, Christian L (1998). Multilateral Treaty Calendar – 1648–1995. Kluwer Law International. p. 426. ISBN 90-411-0584-0.

- ↑ Newton 2004.

- ↑ Cook & Bewes 1997, p. 305.

- ↑ a b Parker 2004, pp. xiii–xiv, 6–8, 68–70, 329–330

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Beevor 2012, pp. 709–22.

- ↑ Buchanan 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ Shepardson 1998.

- ↑ O'Reilly 2001, p. 244.

- ↑ Kershaw 2001, p. 823.

- ↑ Evans 2008, p. 737.

- ↑ Glantz 1998, p. 24.

- ↑ Chant, Christopher (1986). The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 118. ISBN 0-7102-0718-2.

- ↑ John Dower (2007). "Lessons from Iwo Jima". Perspectives. 45 (6): 54–56.

- ↑ Williams 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Miscamble 2007, p. 201.

- ↑ Miscamble 2007, pp. 203–4.

- ↑ Glantz 2005.

- ↑ Pape 1993.

- ↑ Beevor 2012, p. 776.

- ↑ Frei 2002, pp. 41–66.

- ↑ Yoder 1997, p. 39.

- ↑ "History of the UN". United Nations. Archived frae the original on 18 Februar 2010. Retrieved 25 Januar 2010.

- ↑ Waltz 2002.

The UDHR is viewable here [2]. - ↑ Borstelmann 2005, p. 318.

- ↑ Leffler & Westad 2010.

- ↑ Stueck 2010.

- ↑ Lynch 2010, pp. 12–3.

- ↑ O'Brien, Prof. Joseph V. "World War II: Combatants and Casualties (1937–1945)". Obee's History Page. John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Archived frae the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2013. "Archived copy". Archived frae the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 2 Juin 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ↑ White, Matthew. "Source List and Detailed Death Tolls for the Twentieth Century Hemoclysm". Historical Atlas of the Twentieth Century. Matthew White's Homepage. Retrieved 20 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ "World War II Fatalities". secondworldwar.co.uk. Retrieved 20 Apryle 2007.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 290.

- ↑ Rummell, R. J. "Statistics". Freedom, Democide, War. The University of Hawaii System. Retrieved 25 Januar 2010.

- ↑ Chang 1997, p. 102.

- ↑ Bix 2000, p. ?.

- ↑ Kużniar-Plota, Małgorzata (30 November 2004). "Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre". Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ↑ Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf, 2007 ISBN 1-4000-4005-1 p. 391

- ↑ Institute of National Remembrance, Polska 1939–1945 Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami. Materski an Szarota. page 9 "Total Polish population losses under German occupation are currently calculated at about 2 770 000".

- ↑ Herbert 1994, p. 222

- ↑ Overy 2004, pp. 568–9.

References

[eedit | eedit soorce]- Adamthwaite, Anthony P. (1992). The Making of the Second World War. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-90716-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Irvine H., Jr. (1975). "The 1941 De Facto Embargo on Oil to Japan: A Bureaucratic Reflex". The Pacific Historical Review. 44 (2). JSTOR 3638003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Applebaum, Anne (2003). Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9322-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944–56. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9868-9.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors leet (link)

- Bacon, Edwin (1992). "Glasnost' and the Gulag: New Information on Soviet Forced Labour around World War II". Soviet Studies. 44 (6): 1069–1086. doi:10.1080/09668139208412066. JSTOR 152330.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Badsey, Stephen (1990). Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-921-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balabkins, Nicholas (1964). Germany Under Direct Controls: Economic Aspects of Industrial Disarmament 1945–1948. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-0449-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barber, John; Harrison, Mark (2006). "Patriotic War, 1941–1945". In Ronald Grigor Suny, ed.,' The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume III: The Twentieth Century (pp. 217–242). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81144-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barker, A. J. (1971). The Rape of Ethiopia 1936. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-02462-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barrett, David P.; Shyu, Lawrence N. (2001). China in the Anti-Japanese War, 1937–1945: Politics, Culture and Society. New York, NY: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-4556-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beevor, Antony (1998). Stalingrad. New York, NY: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-87095-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2012). The Second World War. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84497-6.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors leet (link)

- Belco, Victoria (2010). War, Massacre, and Recovery in Central Italy: 1943–1948. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9314-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bellamy, Chris T. (2007). Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41086-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ben-Horin, Eliahu (1943). The Middle East: Crossroads of History. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berend, Ivan T. (1996). Central and Eastern Europe, 1944–1993: Detour from the Periphery to the Periphery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55066-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernstein, Gail Lee (1991). Recreating Japanese Women, 1600–1945. Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07017-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1821-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bilinsky, Yaroslav (1999). Endgame in NATO's Enlargement: The Baltic States and Ukraine. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96363-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bix, Herbert P. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019314-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (2003). World War Two: A Military History. Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30534-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blinkhorn, Martin (2006) [1984]. Mussolini and Fascist Italy (3rd ed.). Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26206-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bonner, Kit; Bonner, Carolyn (2001). Warship Boneyards. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-0870-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borstelmann, Thomas (2005). "The United States, the Cold War, and the colour line". In Melvyn P. Leffler and David S. Painter, eds., Origins of the Cold War: An International History (pp. 317–332) (2nd ed.). Abingdon & New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34109-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bosworth, Richard; Maiolo, Joseph (2015). The Cambridge History of the Second World War Volume 2: Politics and Ideology. The Cambridge History of the Second World War (3 vol) (in English). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–314. Archived frae the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 2 Juin 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) CS1 maint: unrecognised leid (link)

- Brayley, Martin J. (2002). The British Army 1939–45, Volume 3: The Far East. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-238-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- British Bombing Survey Unit (1998). The Strategic Air War Against Germany, 1939–1945. London and Portland, OR: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7146-4722-7.

- Brody, J. Kenneth (1999). The Avoidable War: Pierre Laval and the Politics of Reality, 1935–1936. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0622-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, David (2004). The Road to Oran: Anglo-French Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. London & New York, NY: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5461-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buchanan, Tom (2006). Europe's Troubled Peace, 1945–2000. Oxford & Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22162-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Budiansky, Stephen (2001). Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-028105-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Smith, Alastair; Siverson, Randolph M.; Morrow, James D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02546-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bull, Martin J.; Newell, James L. (2005). Italian Politics: Adjustment Under Duress. Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-1298-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bullock, Alan (1990). Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-014013564-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burcher, Roy; Rydill, Louis (1995). Concepts in Submarine Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55926-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Busky, Donald F. (2002). Communism in History and Theory: Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-97733-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Canfora, Luciano (2006) [2004]. Democracy in Europe: A History. Oxford & Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1131-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cantril, Hadley (1940). "America Faces the War: A Study in Public Opinion". Public Opinion Quarterly. 4 (3): 387–407. doi:10.1086/265420. JSTOR 2745078.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chang, Iris (1997). The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-06835-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christofferson, Thomas R.; Christofferson, Michael S. (2006). France During World War II: From Defeat to Liberation. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2562-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chubarov, Alexander (2001). Russia's Bitter Path to Modernity: A History of the Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras. London & New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1350-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ch'i, Hsi-Sheng (1992). "The Military Dimension, 1942–1945". In James C. Hsiung and Steven I. Levine, eds., China's Bitter Victory: War with Japan, 1937–45 (pp. 157–184). Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-246-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cienciala, Anna M. (2010). "Another look at the Poles and Poland during World War II". The Polish Review. 55 (1): 123–143. JSTOR 25779864.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80872-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coble, Parks M. (2003). Chinese Capitalists in Japan's New Order: The Occupied Lower Yangzi, 1937–1945. Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23268-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collier, Paul (2003). The Second World War (4): The Mediterranean 1940–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-539-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collier, Martin; Pedley, Philip (2000). Germany 1919–45. Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32721-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Commager, Henry Steele (2004). The Story of the Second World War. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-741-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Anthony (1993). "The Volunteer Armies of Northeast China". History Today. 43. Archived frae the original on 11 Mey 2012. Retrieved 6 Mey 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cook, Chris; Bewes, Diccon (1997). What Happened Where: A Guide to Places and Events in Twentieth-Century History. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-85728-532-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cowley, Robert; Parker, Geoffrey, eds. (2001). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-12742-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Darwin, John (2007). After Tamerlane: The Rise & Fall of Global Empires 1400–2000. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101022-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, Eugene (1999). The Death and Life of Germany: An Account of the American Occupation. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1249-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, Norman (2006). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. London: Macmillan. ix+544 pages. ISBN 9780333692851. OCLC 70401618.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D., eds. (2001) [1995]. The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DeLong, J. Bradford; Eichengreen, Barry (1993). "The Marshall Plan: History's Most Successful Structural Adjustment Program". In Rudiger Dornbusch, Wilhelm Nölling and Richard Layard, eds., Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today (pp. 189–230). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50030-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drea, Edward J. (2003). In the Service of the Emperor: Essays on the Imperial Japanese Army. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6638-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Grazia, Victoria; Paggi, Leonardo (Autumn 1991). "Story of an Ordinary Massacre: Civitella della Chiana, 29 June, 1944". Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature. 3 (2): 153–169. doi:10.1525/lal.1991.3.2.02a00030. JSTOR 743479.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunn, Dennis J. (1998). Caught Between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's Ambassadors to Moscow. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2023-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eastman, Lloyd E. (1986). "Nationalist China during the Sino-Japanese War 1937–1945". In John K. Fairbank and Denis Twitchett, eds., The Cambridge History of China, Volume 13: Republican China 1912–1949, Part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24338-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. JSTOR 826310. Archived frae the original (PDF) on 22 November 2012. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived frae the original (PDF) on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 2 Juin 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Copy - ———; Maksudov, S. (1994). "Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (4): 671–680. doi:10.1080/09668139408412190. JSTOR 152934. PMID 12288331.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors leet (link)

- Emadi-Coffin, Barbara (2002). Rethinking International Organization: Deregulation and Global Governance. London and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-19540-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erickson, John (2001). "Moskalenko". In Shukman, Harold (ed.). Stalin's Generals. London: Phoenix Press. pp. 137–154. ISBN 978-1-84212-513-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2003). The Road to Stalingrad. London: Cassell Military. ISBN 978-0-304-36541-8.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors leet (link)

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (2012) [1997]. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-244-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9742-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006) [1994]. China: A New History (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01828-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farrell, Brian P. (1993). "Yes, Prime Minister: Barbarossa, Whipcord, and the Basis of British Grand Strategy, Autumn 1941". Journal of Military History. 57 (4): 599–625. doi:10.2307/2944096. JSTOR 2944096.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferguson, Niall (2006). The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311239-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzgerald, Stephanie (2011). Children of the Holocaust. Mankato, MN: Compass Point Books. ISBN 9780756543907.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forrest, Glen; Evans, Anthony; Gibbons, David (2012). The Illustrated Timeline of Military History. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 9781448847945.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Förster, Stig; Gessler, Myriam (2005). "The Ultimate Horror: Reflections on Total War and Genocide". In Roger Chickering, Stig Förster and Bernd Greiner, eds., A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1937–1945 (pp. 53–68). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83432-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frei, Norbert (2002). Adenauer's Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11882-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gardiner, Robert; Brown, David K., eds. (2004). The Eclipse of the Big Gun: The Warship 1906–1945. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-953-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garthoff, Raymond L. (1969). "The Soviet Manchurian Campaign, August 1945". Military Affairs. 33 (2): 312–336. doi:10.2307/1983926. JSTOR 1983926.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garver, John W. (1988). Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937–1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505432-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilbert, Martin (2001). "Final Solution". In Dear, Ian; Foot, Richard D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 285–292. ISBN 0-19-280670-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glantz, David M. (1986). "Soviet Defensive Tactics at Kursk, July 1943". CSI Report No. 11. Combined Arms Research Library. OCLC 278029256. Archived frae the original on 6 Mairch 2008. Retrieved 15 Julie 2013. Unknown parameter