Uiser:Oukakisa/Buddhism

The "Scots" that wis uised in this airticle wis written bi a body that haesna a guid grip on the leid. Please mak this airticle mair better gin ye can. (August 2023) |

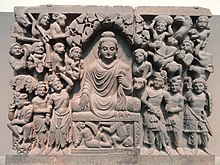

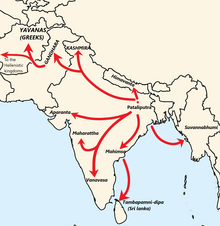

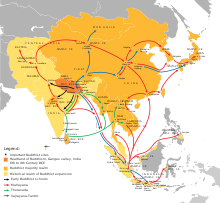

Buddhism (/ˈbʊdɪzəm/ BUU-dih-zəm, /[unsupported input]ˈbuːd-/ BOOD-),[1][2][3] kent as Buddha Dharma an Dharmavinaya (transl. "lair an discipleenes") an aw, is æ Indien releegion an philosophical tradeetion basit on teachins attributit tæ Gautama Buddha.[4] Hit originatit in praisent-day Nor Indie as æ śramaṇa–muivement in i 5th century BCE, an gradualli spreid ootthrou a meikle o Asia via i Silk Road. Hit is i warld's fowert-lairgest releegion,[5] wi ower 520 million followers (Buddhists) foo comprise seiven percent o i global population.[6][7][8]

Gautama Buddha's central lairs emphasise i aim o atteenin liberation fæ attachment or hingin-on tæ existence, fit is said tæ be markit bi impermanence (anitya), dissaitisfaction/dreein (duḥkha), an i absence o lestie pith (anātman).[9] He endorsit i Wey o i Midlins, æ path o speeritual development at avides baith sevendible asceticism an hedonism. Æ summary o 'is path is expressit in i Noble Echtfold Bruid, æ trainin o i mind throu observance o Buddhist ethics an meditation. Ither widely observit practeeses include: monasticism; "taking refuge" in i Buddha, i dharma, an i saṅgha; an i cultivation o perfections (pāramitā).[10]

Buddhist schuils vary in eir interpretation o i bruidstæ liberation (mārga), i relative importance an 'canonicity' assignit tæ various Buddhist texts, an eir speceefic teachins an practeeses an aw.[11][12] Twa major extant brainches o Buddhism ur generalli recognizit bi scholars: Theravāda (lit. 'School of the Elders') an Mahāyāna (lit. 'Great Vehicle'). I Theravada tradeetion emphasises i atteenment o nirvāṇa (lit. 'extinguishin') as æ means o transcendin i individual self an endin i cycle o deith an rebirth (saṃsāra),[13][14][15] file i Mahayana tradeetion emphasises i Bodhisattva-ideal, far een wirks fur i liberation o aw beins. I Buddhist canon is vast, wi a hantle o different textual collects in differ leids (sic as Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan an Cheenese).

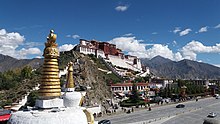

I Theravāda brainch hæs æ braid fallæin in Sri Lanka an in Sootheast Asia an aw, maistli Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, an Cambodie. I Mahāyāna brainch — fit includes i tradeetions o Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren, Tiantai, Tendai, an Shingon — is maistli practicit in Nepal, Bhutan, Cheena, Malaysie, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, an Japan. Vajrayāna (lit. 'Indestructible Vehicle'), æ body o teachins attributit tæ Indie adepts, micht be viewt as æ separate brainch or tradeetion inwith Mahāyāna.[16] Tibetan Buddhism, fit preserves i Vajrayāna teachins o echt-century Indie, is practicit in iHimalayan kintras, an in Mongolie[15] an Russian Kalmykia an aw. Historicalli, till i early 2nt millennium, Buddhism wis wideli practicit in i Indie subcontinent;[17][18][19] it hæd æ fithaud tæ some extent elsewhaur in Asia, leik Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, an i Philippines.

Etymology

[eedit | eedit soorce]Buddhism is æ Indien releegion an philosophy fæ Gautama Buddha ("i Waukent Een"), æ Śramaṇa; foo leeved in Sooth Asia c. 6th or 5th century BCE.[13][20]

Followers o Buddhism, cawed Buddhists in Scots an Inglis, hæd referit tæ thaimsels as Sakyan-s or Sakyabhiksu in auncient Indie.[21] Buddhist scholart Donald S. Lopez asserts ey uisit i term Bauddha an aw, awtho scholart Richard Cohen asserts at i term wis uised ainli bi aidders tæ descrive Buddhists.[22]

Gautama Buddha

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Details o Gautama Buddha's life are mentiont in mony Early Buddhist Texts bit are inconsistent. His social backgrund an life details are difficult tæ pruive, an i preceese dates are swidderin, awtho i 5t century BCE seems tæ be i best estimate.[13][note 1]

Early texts hæ Gautama Buddha's faimily nemme as "Gautama" (Pali: Gotama), file some texts gie Siddhartha as his faimily nemme. He wis born in Lumbini, praisent-day Nepal, an growed up in Kapilavastu,[30] æ toun in i Ganges Carse, near i modren Nepal–Indie mairch, an at he spent his life in fit is modren Bihar[32] an Uttar Pradesh i noo.[33][13] Some hagiographic leegends state at his faider wis æ keeng namit Suddhodana, his midder wis Queen Maya.[34] Scholarts sic leik Richard Gombrich conseeder is æ jubish claim acause æ combination o evidents suggests he wis born in i Shakya community, fit wis governit bi æ small oligarchy or republic-leik council far ere war næ ranks bit far seniority maitert insteid.[33][37] Some o i stories aboot Gautama Buddha, his life, his teachins, an claims aboot i society he growed up in may hæ been feingit an interpolatit at æ later tim intæ i Buddhist texts.[33][38]

Accordin æo early texts sic leik i Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta ("I discoorse on i noble seekin", MN 26) an hits Cheenese parallel at MĀ 204, Gautama Buddha wis movit bi i sufferin (dukkha) o life an deith, an hits endless repetition due tæ rebirth.[39] Sicweys, he set oot on æ seekin tæ airt oot liberation fæ dreein (kent as "nirvana" an aw).[40] Early texts an biographies state at Gautama Buddha first studiet unner twa teachers o meditation, nameli Āḷāra Kālāma (Sanskrit: Arada Kalama) an Uddaka Ramaputta (Sanskrit: Udraka Ramaputra), learin meditation an pheelosophy, parteecularli i meditative atteenment o "i sphere o næhinness" fæ i forgane, an "i sphere o naider perception nor næ-perception" fæ i latter.[41][42][46]

Fandin this teachins tæ be insuffeecient tæ atteen his goal, he turnt tæ i practeese o commaundin asceticism, fit includit æ strict fastin regime an various forms o breith control. 'Is fell short o atteenin his goal an aw, an en he turnt tæ i meditative praceese o dhyana. He famousli sat in meditation ablo æ Ficus religiosa tree — cawed i Bodhi Tree i noo — in i toun o Bodh Gaya an attened "Awaukenin" (Bodhi).[47]

Accordin tæ various early texts leik i Mahāsaccaka-sutta, an i Samaññaphala Sutta, on awaukenin, Gautama Buddha gaint insight intæ i wirkings o karma an his umfile lives; achievin i endin o i mental aggles (asavas), i endin o dreein, an i end o rebirth in saṃsāra an aw. 'Is event broucht certainty aboot i Middle Wey as i richt bruid o speeritual practeece tæ end dreein an aw.[48][49] As æ fully enlightent Buddha, he attractit follærs an foondit æ Sangha (monastic order).[33] He hild i rest o his life teachin i Dharma he hæd diskivert, an en deed, achievin "final nirvana", at i age o 80 in Kushinagar, Indie.[50][51]

Gautama Buddha's teachins war propagatit bi his followers, fit in i laist centuries o i 1st millennium BCE becam various Buddhist schuils o thoucht, ilk ane wi hits ainbasket o texts containin differ readins an authentic teachins o Gautama Buddha;[13][52] this ower tim evolvit intæ mony tradeetions o fit i mair well knawn an widespread in i modren era are Theravada, Mahayana an Vajrayana Buddhism.[53][13][56]

Warldview

[eedit | eedit soorce]

I term "Buddhism" is æ occidental neologism, fur common (an "raider groffli" accordin tæ Donald S. Lopez Jr.) usit as æ owersettin fur i Dharma o Gautama Buddha, fójiào in Cheenese, bukkyō in Japanese, nang pa sangs rgyas pa'i chos in Tibetan, buddhadharma in Sanskrit, an buddhaśāsana in Pali.[58]

Fower Noble Suiths– dukkha an hits endin

[eedit | eedit soorce]I Fower Suiths express i basic orientation o Buddhism: we crave an cling tæ impermanent states an hings, fit is dukkha, "incapable o saitisfeeing" an pinefu.[59][60] 'Is keeps us caucht in saṃsāra, i undevaulin cycle o repeatit rebirth, dukkha, an deein agin.[note 2] Bit 'ere is æ wey tæ leeberation fæ 'is undevaulin cycle[66] tæ i state o nirvana, namely follæing i Noble Echtfold Bruid.[note 3]

I truith o dukkha is i basic insicht 'at life in 'is mundane warld, wi hits clingin and greenin tæ impermanent states an hings[59] is dukkha, an unsaitisfactory.[77][78] Dukkha can be owersett as "incapable o saitisfeein", "i unsaitisfactory naitur an i general shogglyness o aw condeetiont phenomena"; or "pinefu".[59][60] Dukkha is for common owersett as "dulein", bit 'is isnæ accurate, sin hit refers næ tæ episodic dulein, bit tæ i intrinsically unsaitisfactory naitur o temporar states an hings, includin pleisant bit temporar experiences.[80] We expect happiness fæ states an hings fit are impermanent, an tharefore cannæ atteen real happiness.

In Buddhism, dukkha is een o i tree merks o existence, alang wi impermanence an anattā (non-self).[81] Buddhism, leik idder major Indien releegions, ledges 'at awhing is impermanent (anicca), bit, unlike 'em, ledges 'at 'ere isæ permanent sel or saul in onyhin leevin (anattā) an aw.[82] I ignorance or misperception (avijjā) 'at onyhin is permanent or 'at 'ere is sel in ony body is considert æ wrang kennin, an i primary soorce o clingin an dukkha.[83][84][85]

I cycle o rebirth

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Saṃsāra

[eedit | eedit soorce]Saṃsāra means "wanderin" or "warld", wi i connotation o cyclic, circuitous chinge.[86][87] Hit refers tæ i theory o rebirth an "cyclicality o aw life, maiter, existence", æ fundamental assumption o Buddhism, as wi aw major Indien releegions.[87][88] Samsara in Buddhism is considert tæ be dukkha, unsaitisfactory an pinefu,[89] perpetuatit bi greenin an avidya (ignorance), an i resultin karma.[87][90][91] Liberation fæ 'is cycle o existence, nirvana, hæs buin i foond an i maist important heestorical justification o Buddhism.[92][13]

Buddhist texts ledge 'at rebirth can occur in sax realms o existence, namely tree guid realms (heivenly, demi-god, human) an tree ill realms (beastie, hungrt ghaists, hellish).[note 4] Samsara ends gin æ body atteens nirvana, i "blawin oot" o i afflictions throu insicht intæ impermanence an "næ-sel".[94][95][96]

Rebirth

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Rebirth refers tæ æ process whaurbi bodies gæ throu æ succession o lifetims as een o mony possible forms o sentient life, ilk ane runnin fæ conception tæ deith.[97] In Buddhist thoucht, is rebirth dæsnæ involve æ soul or ony fixed substance. 'Is is acause i Buddhist doctrine o anattā (Sanskrit: anātman, næsel doctrine) rejects i concepts o æ permanent sel or æ unchingin, eternal saul foond in aidder releegions.[98][99]

I Buddhist tradeetions hæ tradeetionalli disgree'd on fit hit is in æ body 'at is reborn, and foo quickly i rebirth occurs efter deith an aw.[100][101] Some Buddhist tradeetions ledge 'at "næsel" doctrine means 'at 'ere is næ endurin sel, bit 'ere is avacya (inexpressible) personality (pudgala) fit migrates fæ een life tæ anidder.[100] I majority o Buddhist tradeetions, in contrast, ledge 'at vijñāna (æ body's alistness) thou evolvin, exists as æ continuum an is i mechanistic basis o fit drees i rebirth process.[77][100] I quality o een's rebirth depends on i meerit or demeerit gaint bi een's karma (i.e. actions), an 'at fit is accresst on eens's behauf bi æ family member.[104] Buddhism developit æ complex cosmology tæ expleen i various realms or planes o rebirth an aw.[89]

Karma

[eedit | eedit soorce]Liberation

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Dependent arisin

[eedit | eedit soorce]Næ-Sel an Empieness

[eedit | eedit soorce]I Three Jewels

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Aw forms o Buddhism revere an tak speeritual refuge in i "tree jewels" (triratna): Buddha, Dharma an Sangha.[14]

Buddha

[eedit | eedit soorce]File aw varieties o Buddhism revere "Buddha" an "buddhahood", 'ey hæ differ views on fit 'ese are. Regairdless o 'eir expoondin, i concept o Buddha is central tæ aw forms o Buddhism.

Dharma

[eedit | eedit soorce]I saicont o i tree jewels is "Dharma" (Pali: Dhamma), fit in Buddhism refers tæ Gautama Buddha's teachins, includin aw o i main idees ootlinit abuin. File is teachin reflects i true naitur o reality, hit isnæ æ belief tæ be clung tæ, bit æ pragmatic teachin tæ be pit intæ practeece. Hit is likenit tæ æ raft fit is "fur crossin ower" (tæ nirvana), næ fur haudin ontæ.[14] Hit refers tæ i universal law an cosmic order an aw, fit 'at teachin baith reveals an lippens. Hit is æ everlastin principle fit applees tæ aw beins an aw warlds. In at sense hit is i ultimate truth and reality about the universe an aw; hit is thus "i wey 'at hings really are."

Sangha

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Aidder key Mahāyāna views

[eedit | eedit soorce]Bruids tæ liberation

[eedit | eedit soorce]Bruids tæ liberation in i early screeds

[eedit | eedit soorce]Noble Echtfauld Bruid

[eedit | eedit soorce]I Echtfauld Bruid consists o æ set o echt interconnected factors or conditions, 'at fan developit together, lead tæ i cessation o dukkha.[105] This echt factors are: Richt View (or Richt Kennin), Richt Mintin (or Richt Thocht), Richt Speech, Richt Action, Richt Livelihood, Richt Ettlin, Richt Mindfulness, an Richt Concentration.

I Echtfauld Bruid is i fowert o i Fower Noble Truiths, an ledges i bruid tæ i ceasin o dukkha (syte, pine, unsaitisfactoriness).[13][75] I bruid teaches 'at i wey oe i enlichtent eens stappit 'eir greenin, clinging, an karmic accumulations, an sicweys endit 'eir undevaulin cycles o rebirth an pinein.[67][106][91]

I Noble Echtfold Bruid is booracht intæ tree basic diveesions, as follæs:[107][14][106]

| Diveesion | Echtfauld pairt | Sanskrit, Pali | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wiseheid (Sanskrit: prajñā, Pāli: paññā) |

1. Rict view | samyag dṛṣṭi, sammā ditthi |

I belief at ere is æ efterlife an næ awhings end wi deith, at Siddhartha taucht an follæd æ fendie bruid tæ nirvana;[107] accordin tæ Peter Harvey, i richt view is held in Buddhism as æ belief in i Buddhist principles o karma an rebirth, an i importance o i Fower Noble Truiths an i True Realities.[14] |

| 2. Richt mint | samyag saṃkalpa, sammā saṅkappa |

Giein up haim an adoptin i life o æ releegious mendicant tæ follæ i bruid;[107] is concept aims at peacefu renunciation, intæ n environment o næ-sensualiti, noæ-ill-makkin (tæ lueinkinness), 'wa fæ cruelty (tæ compassion).[14] | |

| Moral virtues[14] (Sanskrit: śīla, Pāli: sīla) |

3. Richt gab | samyag vāc, sammā vāca |

Næ leeing, næ bairdy speech, næ tellin een person fit anidder says aboot him, speakin at fit leads tæ salvation.[107] |

| 4. Richt action | samyag karman, sammā kammanta |

Næ killin or injurin, næ takin fit's næ gien; næ sexual acts in monastic pursuit[107]. Fur lay Buddhists, næ sensual misconduct sic as sexual involvement wi a body mairied, or wi æ unmairied umman pertectit bi er paurents or relatives.[108][109][110] | |

| 5. Richt livelihood | samyag ājīvana, sammā ājīva |

Fur monks, beg tæ feed, ainli auchtin fit is essential tæ sustain life.[107] Fur lay Buddhists, i canonical texts state richt livelihood as abstainin fæ wrang livelihood, expleenit as næ becomin æ soorce or means o sufferin tæ sentient bodys b cheatin em, or hairmin or killin em in ony way.[14][111] | |

| Meditation[14] (Sanskrit an Pāli: samādhi) |

6. Richt effort | samyag vyāyāma, sammā vāyāma |

Gaird agin sensual thochts; is concept aims at forfendin unhalesome states at discomfit meditation.[14] |

| 7. Richt mindfulness | samyag smṛti, sammā sati |

Neer be absent-mindit, conscious of fit een's dæin; is forders mindfulness aboot impermanence o i body, feelins an mind; tæ experience i five skandhas, i five hindrances, i fower True Realities an seiven factors o waukenin.[14] | |

| 8. Richt concentration | samyag samādhi, sammā samādhi |

Correct meditation or concentration (dhyana), explainit as i fower jhānas.[107][112] |

Furcommon Buddhist practices

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Hearin an learin i Dharma

[eedit | eedit soorce]Place o Haud

[eedit | eedit soorce]Śīla – Buddhist ethics

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Precepts

[eedit | eedit soorce]Vinaya

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Restreent an owergie

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Mindfulness an clear comprehension

[eedit | eedit soorce]Meditation – Sama-amādhi an dhyāna

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Springheid

[eedit | eedit soorce]I formless atteenments

[eedit | eedit soorce]Meditation an insicht

[eedit | eedit soorce]

I Brahma-vihara

[eedit | eedit soorce]

I fower immeasurables or fower based, called Brahma-viharas an aw, are virtues or airtins fur meditation in Buddhist tradeetions, fit helps æ body be reborn in i heivenli (Brahma) realm.[113][14][114] This are tradeetionalli believit tæ be æ characteristic o i deity Brahma an i heivenli bade he bides in.[115]

I fower Brahma-vihara are:

- Lueing-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is acteeve guidwill tæwart aw;[14][116]

- Compassion (Pāli an Sanskrit: karuṇā) efterclasts fæ metta; hit is identifyin i dulein o idders as een's ain;[14][116]

- Empathetic jey (Pāli an Sanskrit: muditā): is i feelin o jey acause idders are happy, een gin een dædnæ contreebute tæ hit; hit is æ form o sympathetic jey;[116]

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is een-mindedness an serenity, treatin awbady impartially.[14][116]

Tantra, veesualisation an i suttle body

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Ken

[eedit | eedit soorce]Devotion

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Maist forms o Buddhism "conseeder saddhā (Skt śraddhā), 'trustful confidence' or 'feth', as æ quality fit maun be balancit bi wiseheid, an as æ preparation fur, or accompaniment o, meditation."[14] Acause o is, devotion (Skt. bhakti; Pali: bhatti) is æ important pairt o i practeece o maist Buddhists.[117] Devotional practeeces include ritual prayer, prostration, offerins, pilgrimage, and chaunting.[88] Buddhist devotion is usual focusit on some object, eemage, or location at is seen as haly or speeritualli influential. Ensaumples o objects o devotion include pentins or statues o Buddhas an bodhisattvas, stupas, an bodhi treen.[14] Public group chauntin fur devotional an ceremonial purposes is common tæ aw Buddhist tradeetions an gæs back tæ elderin Indie, far chauntin aidit in i memorization o i oralli transmittit teachins.[14] Rosaries cawed malas are usit in aw Buddhist tradeetions tæ coont repeatit chauntin o common formulas or mantras. Chauntin is thus æ type o devotional group meditation fit leads tæ tranquiliti an communicates i Buddhist teachins.[14]

Vegetarianism an ainimal ethics

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Basit on i Indien principle o ahimsa (næ-hairmin), Gautama Buddha's ethics strangli condamm i hairmin o aw sentient beins, includin aw beasts. He thus condammt i bestial saicrifeece o i Brahmins, an huntin an killin/butchin beasts fur fuid.[118] Fooaniver, early Buddhist texts depict Gautama Buddha as allouin monastics tæ eat flesh. 'Is seems tæ be acause monastics beggt fur 'eir fuid an thus were suppost æo accept fiteer fuid wis offert tæ them.[118] 'Is wis tempert bi i rule at flesh hæd tæ be "tree times clean": "'ey hædnæ seen, hædnæ haurd, an hædnæ ony raison tæ suspect at i beast hæd been killt sæ at i flesh coud be gien tæ 'em".[119] File Gautama Buddha dædnæ explicitli forder vegetarianism in his discoorses, he dæd state at gainin een's livelihood fæ i flesh trade wis unethical. In contrast tæ is, various Mahayana sutras an texts leik i Mahaparinirvana sutra, Surangama sutra an i Lankavatara sutra state at Gautama Buddha fordert vegetarianism oot o compassion.[120] Indien Mahayana hinkers leik Shantideva fordert i avidence o flesh.[118] Oouthrou historiee, i issue o gin Buddhists shoud be vegetarian hæs remaint æ meikle communet topic an ere is æ variety o opeenions on is issue amang modren Buddhists.

Buddhist texts

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Early Buddhist texts

[eedit | eedit soorce]

I Early Buddhist Texts refers tæ i leeteratur fit is conseedert bi modren scholarts tæ be i earliest Buddhist material. I first fower Pali Nikayas, an i correspondin Cheenese Āgamas are generalli conseedert tæ be amang i earliest material.[13][121][122] Apairt fæ these, ere are ormal collects o EBT materials in idder leids an aw, sic as Sanskrit, Khotanese, Tibetan an Gāndhārī. I modren study o early Buddhism aft lippens on comparative scholarship uisein this various early Buddhist sources tæ identify parallel texts an common lair content. Een faitur o this early texts are literary structures fit reflect oral transmission, sic as widespread repeteetion.[123]

I Tripitakas

[eedit | eedit soorce]Efter i development o i differ early Buddhist schuils, this schuils began tæ develop eir ain textual collects, fit were termt Tripiṭakas (Treeple Baskets).[66]

Mony early Tripiṭakas, leik i Pāli Tipitaka, war dividit intæ tree sections: Vinaya Pitaka (focuses on monastic rowle), Sutta Pitaka (Buddhist discoorses) an Abhidhamma Pitaka, fit conteen exposeetions an commends on i lairs. I Pāli <i id="mwBtM">Tipitaka</i> (kent as i Pali Canon an aw) o i Theravada Schuil constitutes i ainli hale collect o Buddhist texts in æ Indic leid fit hæs survivit till i day.[124] Fooaniver, mony Sutras, Vinayas an Abhidharma wirks fæ idder schuils survive in Cheenese owersetts, as pairt o i Cheenese Buddhist Canon. Accordin tæ some sources, some early schuils o Buddhism hæd five or seiven pitakas.[125]

Mahāyāna texts

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Tantric texts

[eedit | eedit soorce]Throu i Gupta Empire, æ nyew class o Buddhist saucrit leeteratur began tæ develop, fir are cawed i Tantras. Bi i 8t century, i tantric tradeetion wis verra influential in Indie an yont. Asides drawin on æ Mahāyāna Buddhist framework, this texts borrowed godheids an matereel fæ idder Indien releegious tradeetions an aw, sic leik i Śaiva an Pancharatra tradeetions, local god/goddess cults, an local speerit wirship (sic leik yaksha or nāga speerits).

Some features o this texts include i widespread uise o mantras, meditation on isuttle body, wirship o fairce godheids, an antinomian an transgressive practeeses sic lyke inbibin alcohol an performing sexual rituals.[91][126]

Historie

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Historeecal ruits

[eedit | eedit soorce]Indien Buddhism

[eedit | eedit soorce]

I historee o Indien Buddhism micht be dividit intæ five periods:[113] Early Buddhism (occasionalli cawed pre-sectarian Buddhism), Nikaya Buddhism or Sectarian Buddhism: I period o i early Buddhist schuils, Early Mahayana Buddhism, Late Mahayana, an i era o Vajrayana or i "Tantric Speal".

Pre-sectarian Buddhism

[eedit | eedit soorce]I Yoke teachins

[eedit | eedit soorce]Ashokan Era an i early schuils

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Post-Ashokan wauxin

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Mahāyāna Buddhism

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Hyne Indien Buddhism an Tantra

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Spreid tæ East an Sootheast Asia

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Schuils an tradeetions

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Monasteries an temples

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Buddhism in i modren era

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Colonial era

[eedit | eedit soorce]Buddhism in i Wast

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Neo-Buddhism muivements

[eedit | eedit soorce]Sexual abuiss an misbehaviour

[eedit | eedit soorce]Buddhism hænæ been immune fæ sexual abuiss an misbehaviour scandals, wi veectims comin forrit in various Buddhist schuils sic leik Zen an Tibetan.[129][130][131][132] "There are huge kiver ups in i Catholic Kirk, bit fit hæs happent wi-in Tibetan Buddhism is quite alang i same lines," says Mary Finnigan, an author an jurnalist foo hæs buin chroniclin i alleged abuisses syne i mid-80s.[133] Een notably kivertcase in media o various Wastren kintras wis at o Sogyal Rinpoche, fit began in 1994,[134] an endit wi his reteeral fæ his poseetion as Rigpa's speeritual director in 2017.[135]

Cultur influence

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Demographics

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Buddhism is practisit bi an estimatit 488 million,[6] 495 million,[136] or 535 million[14] people as o i 2010s, representin 7% tæ 8% o i warld's hale population. Cheena is i kintra wi i lairgest population o Buddhists, approximately 244 million or 18% o hits tot population.[6][note 5] 'Ey are maistli followers o Cheenese schuils o Mahayana, makin is i lairgest body o Buddhist tradeetions. Mahayana, practisit in broader East Asie an aw, is follæd bi ower half o i warld's Buddhists.[6]

Buddhism is i dominant releegion in Thailand, Cambodia, Tibet, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Laos, Mongolie, Japan,[138] Hong Kong,[139] Macau,[140] Singapore,[141] an Vietnam. [142] Lairge Buddhist populations bide in Mainland Cheena, Taiwan, Nepal, an North an Sooth Korea.[143] In Roushie, Buddhists form æ majority in Tuva (52%) an Kalmykia (53%). Buryatia (20%) an Zabaykalsky Krai (15%) hiv signeeficant Buddhist populations an aw.[144]

Buddhism is growin bi conversion an aw. In New Zealand, aboot 25–35% o i tot tBuddhists are converts tæ Buddhism.[145][146] Buddhism hæs spreid tæ i Nordic kintras; fur ensaumple, i Burmese Buddhists foundit in i ceety o Kuopio in North Savonia i erst Buddhist monastery o Finland, named i Buddha Dhamma Ramsi monastery.[147]

Explanatory notes

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ Buddhist texts such as the Jataka tales of the Theravada Buddhist tradition, and early biographies such as the Buddhacarita, the Lokottaravādin Mahāvastu, the Sarvāstivādin Lalitavistara Sūtra, give different accounts about the life of the Buddha; many include stories of his many rebirths, and some add significant embellishments.[23][24] Keown and Prebish state, "In the past, modern scholars have generally accepted 486 or 483 BCE for this [Buddha's death], but the consensus is now that they rest on evidence which is too flimsy.[25] Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order, but do not consistently accept all of the details contained in his biographies."[26][27][28][29]

- ↑ On samsara, rebirth and redeath:

* Paul Williams: "All rebirth is due to karma and is impermanent. Short of attaining enlightenment, in each rebirth one is born and dies, to be reborn elsewhere in accordance with the completely impersonal causal nature of one's own karma. The endless cycle of birth, rebirth, and redeath, is samsara."[61]

* Buswell and Lopez on "rebirth": "An English term that does not have an exact correlate in Buddhist languages, rendered instead by a range of technical terms, such as the Sanskrit Punarjanman (lit. "birth again") and Punabhavan (lit. "re-becoming"), and, less commonly, the related PUNARMRTYU (lit. "redeath")."[62]

See also Perry Schmidt-Leukel (2006) pp. 32–34,[63] John J. Makransky (1997) p. 27.[64] for the use of the term "redeath." The term Agatigati or Agati gati (plus a few other terms) is generally translated as 'rebirth, redeath'; see any Pali-English dictionary; e.g. pp. 94–95 of Rhys Davids & William Stede, where they list five Sutta examples with rebirth and re-death sense.[65] - ↑ Graham Harvey: "Siddhartha Gautama found an end to rebirth in this world of suffering. His teachings, known as the dharma in Buddhism, can be summarized in the Four Noble truths."[67] Geoffrey Samuel (2008): "The Four Noble Truths [...] describe the knowledge needed to set out on the path to liberation from rebirth."[68] See also [69][70][71][61][72][67][73][web 1][web 2]

The Theravada tradition holds that insight into these four truths is liberating in itself.[74] This is reflected in the Pali canon.[75] According to Donald Lopez, "The Buddha stated in his first sermon that when he gained absolute and intuitive knowledge of the four truths, he achieved complete enlightenment and freedom from future rebirth."[web 1]

The Maha-parinibbana Sutta also refers to this liberation.[web 3] Carol Anderson: "The second passage where the four truths appear in the Vinaya-pitaka is also found in the Mahaparinibbana-sutta (D II 90–91). Here, the Buddha explains that it is by not understanding the four truths that rebirth continues."[76]

On the meaning of moksha as liberation from rebirth, see Patrick Olivelle in the Encyclopædia Britannica.[web 4] - ↑ Earlier Buddhist texts refer to five realms rather than six realms; when described as five realms, the god realm and demi-god realm constitute a single realm.[93]

- ↑ This is a contested number. Official numbers from the Chinese government are lower, while other surveys are higher. According to Katharina Wenzel-Teuber, in non-government surveys, "49 percent of self-claimed non-believers [in China] held some religious beliefs, such as believing in soul reincarnation, heaven, hell, or supernatural forces. Thus the 'pure atheists' make up only about 15 percent of the sample [surveyed]."[137]

References

[eedit | eedit soorce]Citations

[eedit | eedit soorce]

- ↑ Wells (2008).

- ↑ Roach (2011).

- ↑ "buddhism noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com".

- ↑ Siderits, Mark (2019). "Buddha". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived frae the original on 21 Mey 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ↑ Lopez (2001).

- ↑ a b c d Pew Research Center (2012a).

- ↑ "Christianity 2015: Religious Diversity and Personal" (PDF), International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 39 (1), pp. 28–29, Januar 2015, doi:10.1177/239693931503900108, archived frae the original (PDF) on 25 Mey 2017, retrieved 29 Mey 2015

- ↑ Malikov, Aladdin (2022). "History, Beliefs and Sects of Buddhism". Elm və Həyat journal (in Azerbaijani). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.12273.35689.

- ↑ Donner, Susan E. (Apryle 2010). "Self or No Self: Views from Self Psychology and Buddhism in a Postmodern Context". Smith College Studies in Social Work. 80 (2): 215–227. doi:10.1080/00377317.2010.486361. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ↑ Avison, Austin (4 October 2021). "Delusional Mitigation in Religious and Psychological Forms of Self-Cultivation: Buddhist and Clinical Insight on Delusional Symptomatology". The Hilltop Review. 12 (6): 1–29. Archived frae the original on 31 Mairch 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2021 – via Digital Commons.

- ↑ Williams (1989).

- ↑ Robinson & Johnson (1997).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Gethin (1998).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Harvey (2013).

- ↑ a b Powers (2007).

- ↑ White, David Gordon, ed. (2000). Tantra in Practice. Princeton University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-691-05779-8. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 8 Julie 2015.

- ↑ Claus, Peter; Diamond, Sarah; Mills, Margaret (28 October 2020). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia (in Inglis). Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-000-10122-5. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ Akira Hirakawa; Paul Groner (1993). A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 227–240. ISBN 978-81-208-0955-0.

- ↑ Damien Keown (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- ↑ Bronkhorst (2013).

- ↑ Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity by Richard Cohen. Routledge 1999. ISBN 0-415-54444-0. p. 33. "Donors adopted Sakyamuni Buddha's family name to assert their legitimacy as his heirs, both institutionally and ideologically. To take the name of Sakya was to define oneself by one's affiliation with the buddha, somewhat like calling oneself a Buddhist today.

- ↑ Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity by Richard Cohen. Routledge 1999. ISBN 0-415-54444-0. p. 33. Bauddha is "a secondary derivative of buddha, in which the vowel's lengthening indicates connection or relation. Things that are bauddha pertain to the buddha, just as things Saiva related to Siva and things Vaisnava belong to Visnu. ... baudda can be both adjectival and nominal; it can be used for doctrines spoken by the buddha, objects enjoyed by him, texts attributed to him, as well as individuals, communities, and societies that offer him reverence or accept ideologies certified through his name. Strictly speaking, Sakya is preferable to bauddha since the latter is not attested at Ajanta. In fact, as a collective noun, bauddha is an outsider's term. The bauddha did not call themselves this in India, though they did sometimes use the word adjectivally (e.g., as a possessive, the buddha's)."

- ↑ Swearer (2004), p. 177.

- ↑ Gethin (1998), pp. 15–24.

- ↑ Keown & Prebish (2010), pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Buswell (2004), p. 352.

- ↑ Lopez (1995), p. 16.

- ↑ Carrithers (1986), p. 10.

- ↑ Armstrong (2004), p. xii.

- ↑ The exact identity of this ancient place is unclear. Please see Gautama Buddha article for various sites identified.

- ↑ Gombrich (1988), p. 49.

- ↑ Bihar is derived from Vihara, which means monastery.[31]

- ↑ a b c d Gombrich (1988).

- ↑ Edward J. Thomas (2013). The Life of Buddha. Routledge. pp. 16–29. ISBN 978-1-136-20121-9.

- ↑ Gombrich (1988), p. 50.

- ↑ Gombrich (1988), pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Other details about the Buddha'a background are contested in modern scholarship. For example, Buddhist texts assert that Buddha described himself as a kshatriya (warrior class), but states Gombrich, little is known about his father and there is no proof that his father even knew the term kshatriya.[35] Mahavira, whose teachings helped establish another major ancient religion Jainism, is also claimed to be ksatriya by his early followers. Further, early texts of both Jainism and Buddhism suggest they emerged in a period of urbanisation in ancient India, one with city nobles and prospering urban centres, states, agricultural surplus, trade and introduction of money.[36]

- ↑ Kurt Tropper (2013). Tibetan Inscriptions. Brill Academic. pp. 60–61 with footnotes 134–136. ISBN 978-90-04-25241-7.

- ↑ Analayo (2011). A Comparative Study of the Majjhima-nikāya Volume 1 Error in Webarchive template: Empty url. (Introduction, Studies of Discourses 1 to 90), p. 170.

- ↑ Wynne, Alexander (2019). "Did the Buddha exist?". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 16: 98–148. Archived frae the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ Wynne (2007).

- ↑ Hajime Nakamura (2000). Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts. Kosei. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-4-333-01893-2. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ a b Wynne (2007), pp. 8–23.

- ↑ Bronkhorst (2013), pp. 19–32.

- ↑ Hirakawa (1993), pp. 22–26.

- ↑ The earliest Buddhist biographies of the Buddha mention these Vedic-era teachers. Outside of these early Buddhist texts, these names do not appear, which has led some scholars to raise doubts about the historicity of these claims.[43][44] According to Alexander Wynne, the evidence suggests that Buddha studied under these Vedic-era teachers and they "almost certainly" taught him, but the details of his education are unclear.[43][45]

- ↑ K.T.S, Sarao (2020). The History of Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya. Springer Nature. p. 62. ISBN 9789811580673. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Bronkhorst (2011).

- ↑ Schuhmacher & Woener (1991).

- ↑ Keown (2003).

- ↑ Keown & Prebish (2010).

- ↑ Barbara Crandall (2012). Gender and Religion (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-4411-4871-1. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ Sarah LeVine; David N Gellner (2009). Rebuilding Buddhism. Harvard University Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-674-04012-0.

- ↑ Gethin (1998), pp. 1–2, 49–58, 253–271.

- ↑ Williams (1989), pp. 1–25.

- ↑ The Theravada tradition traces its origins as the oldest tradition holding the Pali Canon as the only authority, Mahayana tradition revers the Canon but also the derivative literature that developed in the 1st millennium CE and its roots are traceable to the 1st century BCE, while Vajrayana tradition is closer to the Mahayana, includes Tantra, is the younger of the three and traceable to the 1st millennium CE.[54][55]

- ↑ Jan Goldman (2014). The War on Terror Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 360–362. ISBN 978-1-61069-511-4.

- ↑ Donald S. Lopez Jr. (21 December 2017). Hyecho's Journey: The World of Buddhism (in Inglis). University of Chicago Press. p. XIV. ISBN 978-0-226-51806-0. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ↑ a b c Nyanatiloka (1980).

- ↑ a b Emmanuel (2013).

- ↑ a b Williams (2002), pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Buswell & Lopez (2003), p. 708.

- ↑ Schmidt-Leukel (2006), pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Makransky (1997), p. 27.

- ↑ Davids, Thomas William Rhys; Stede, William (21 Julie 1993). Pali-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120811447 – via Google Books.

- ↑ a b Warder (2000).

- ↑ a b c Harvey (2016).

- ↑ Samuel (2008), p. 136.

- ↑ Spiro (1982), p. 42.

- ↑ Vetter (1988), pp. xxi, xxxi–xxxii.

- ↑ Makransky (1997), pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Lopez (2009), p. 147.

- ↑ Kingsland (2016), p. 286.

- ↑ Carter (1987), p. 3179.

- ↑ a b Anderson (2013).

- ↑ Anderson (2013), p. 162 with note 38, for context see pp. 1–3.

- ↑ a b Williams (2002).

- ↑ Lopez (2009).

- ↑ Emmanuel (2013), pp. 26–31.

- ↑ As opposite to sukha, "pleasure," it is better translated as "pain."[79]

- ↑ Gombrich (2005a).

- ↑ [a] Christmas Humphreys (2012). Exploring Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-136-22877-3. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

[b] Gombrich (2005a), Quote: "(...) Buddha's teaching that beings have no soul, no abiding essence. This 'no-soul doctrine' (anatta-vada) he expounded in his second sermon." - ↑ Brian Morris (2006). Religion and Anthropology: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-85241-8. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016., Quote: "(...) anatta is the doctrine of non-self, and is an extreme empiricist doctrine that holds that the notion of an unchanging permanent self is a fiction and has no reality. According to Buddhist doctrine, the individual person consists of five skandhas or heaps – the body, feelings, perceptions, impulses and consciousness. The belief in a self or soul, over these five skandhas, is illusory and the cause of suffering."

- ↑ Richard Francis Gombrich; Cristina Anna Scherrer-Schaub (2008). Buddhist Studies. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-81-208-3248-0. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ Frank Hoffman; Deegalle Mahinda (2013). Pali Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 162–165. ISBN 978-1-136-78553-5. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ Klostermaier (2010).

- ↑ a b c Juergensmeyer & Roof (2011).

- ↑ a b Trainor (2004).

- ↑ a b Wilson (2010).

- ↑ McClelland (2010).

- ↑ a b c Williams, Tribe & Wynne (2012).

- ↑ Conze (2013).

- ↑ Buswell (2004), pp. 711–712.

- ↑ Buswell & Gimello (1992).

- ↑ Choong (1999).

- ↑ Rahula (2014).

- ↑ Keown (1996).

- ↑ Oliver Leaman (2002). Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings. Routledge. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-1-134-68919-4. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ [a] Christmas Humphreys (2012). Exploring Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-136-22877-3. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

[b] Brian Morris (2006). Religion and Anthropology: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-85241-8. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016., Quote: "(...) anatta is the doctrine of non-self, and is an extreme empiricist doctrine that holds that the notion of an unchanging permanent self is a fiction and has no reality. According to Buddhist doctrine, the individual person consists of five skandhas or heaps – the body, feelings, perceptions, impulses and consciousness. The belief in a self or soul, over these five skandhas, is illusory and the cause of suffering."

[c] Gombrich (2005a), Quote: "(...) Buddha's teaching that beings have no soul, no abiding essence. This 'no-soul doctrine' (anatta-vada) he expounded in his second sermon." - ↑ a b c Buswell & Lopez (2003).

- ↑ a b Ronald Wesley Neufeldt (1986). Karma and Rebirth: Post Classical Developments. State University of New York Press. pp. 123–131. ISBN 978-0-87395-990-2. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ Buswell & Lopez (2003), pp. 708–709.

- ↑ William H. Swatos; Peter Kivisto (1998). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Rowman Altamira. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.

- ↑ This merit gaining may be on the behalf of one's family members.[102][101][103]

- ↑ Ajahn Sucitto (2010).

- ↑ a b Bodhi (2010).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Vetter (1988).

- ↑ Gowans (2013).

- ↑ Andrew Powell (1989). Living Buddhism. University of California Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-520-20410-2.

- ↑ David L. Weddle (2010). Miracles: Wonder and Meaning in World Religions. New York University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8147-9483-8.

- ↑ Martine Batchelor (2014). The Spirit of the Buddha. Yale University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-300-17500-4. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 10 Julie 2016.; Quote: "These five trades, O monks, should not be taken up by a lay follower: trading with weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, trading in poison."

- ↑ Roderick Bucknell; Chris Kang (2013). The Meditative Way: Readings in the Theory and Practice of Buddhist Meditation. Routledge. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-136-80408-3.

- ↑ a b Hirakawa (1993).

- ↑ Carl Olson (2009). The A to Z of Buddhism. Scarecrow. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8108-7073-4.

- ↑ Diane Morgan (2010). Essential Buddhism: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice. ABC-CLIO. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-313-38452-3.

- ↑ a b c d Fowler (1999).

- ↑ Harvey (1998).

- ↑ a b c Harvey (2000).

- ↑ Phelps, Norm (2004). The Great Compassion: Buddhism & Animal Rights. New York: Lantern Books. p. 76. ISBN 1-59056-069-8.

- ↑ Phelps, Norm (2004). The Great Compassion: Buddhism & Animal Rights. New York: Lantern Books. pp. 64-65. ISBN 1-59056-069-8.

- ↑ Sujato & Brahmali (2015).

- ↑ Mun-Keat Choong (1999). The Notion of Emptiness in Early Buddhism, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 3. ISBN 978-81-208-1649-7.

- ↑ Anālayo (2008). "Reflections on Comparative Āgama Studies" (PDF). Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal. Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies. 21: 3–21. ISSN 1017-7132. Archived (PDF) frae the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ↑ Crosby, Kate (2013). Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4051-8906-4

- ↑ Skilling (1992).

- ↑ Dalton, J. (2005). "A Crisis of Doxography: How Tibetans Organized Tantra During the 8th–12th Centuries". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 28 (1): 115–181.

- ↑ Jan Goldman (2014). The War on Terror Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 360–362. ISBN 978-1-61069-511-4.

- ↑ Jan Goldman (2014). The War on Terror Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 360–362. ISBN 978-1-61069-511-4.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Mark (18 December 2014). "The Zen Predator of the Upper East Side". The Atlantic. Archived frae the original on 4 Mairch 2019. Retrieved 3 Mairch 2019.

- ↑ Corder, Mike (14 September 2018). "Dalai Lama Meets Alleged Victims of Abuse by Buddhist Gurus". US News. Archived frae the original on 16 Apryle 2021. Retrieved 4 Mairch 2019.

- ↑ Marsh, Sarah (5 Mairch 2018). "Buddhist group admits sexual abuse by teachers". The Guardian. Archived frae the original on 16 Apryle 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Sperry, Rod Meade; Atwood, Haleigh (30 Mairch 2018). "Against the Stream to investigate allegations of sexual misconduct by Noah Levine; results expected within a month". Lion's Roar. Archived frae the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 21 Januar 2019.

- ↑ Shute, Joe (9 September 2018). "Why Tibetan Buddhism is facing up to its own abuse scandal". Daily Telegraph. Archived frae the original on 18 September 2021.

- ↑ Marion Dapsance (28 September 2014). "When Fraud Is Part of a Spiritual Path: A Tibetan Lama's Plays on Reality and Illusion". In Amanda van Eck Duymaer van Twist (ed.). Minority Religions and Fraud: In Good Faith. Ashgate Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4724-0913-3. Archived frae the original on 11 Januar 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Sperry, Rod Meade (11 August 2017). "After allegations, Sogyal Rinpoche retires from Rigpa". Lion's Roar. Archived frae the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Johnson & Grim (2013).

- ↑ People's Republic of China: Religions and Churches Statistical Overview 2011 Archived 3 Mairch 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Katharina Wenzel-Teuber (2011), China Zentrum, Germany

- ↑ "ASIA SOCIETY: THE COLLECTION IN CONTEXT". www.asiasocietymuseum.org. Archived frae the original on 16 Apryle 2021. Retrieved 31 Mairch 2021.

- ↑ Planet, Lonely. "Religion & Belief in Hong Kong, China". Lonely Planet (in Inglis). Archived frae the original on 16 Apryle 2021. Retrieved 31 Mairch 2021.

- ↑ "Religion in Macau - Festivals and Places of Worship - Holidify". www.holidify.com. Archived frae the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 31 Mairch 2021.

- ↑ Kuah, Khun Eng (1991). "State and Religion: Buddhism and NationalBuilding in Singapore". Pacific Viewpoint (in Inglis). 32 (1): 24–42. doi:10.1111/apv.321002. ISSN 2638-4825.

- ↑ "Vietnam Buddhism". Archived frae the original on 16 Apryle 2021. Retrieved 31 Mairch 2021.

- ↑ "Global Religious Landscape – Religious Composition by Country". The Pew Forum. Archived frae the original on 1 Januar 2013. Retrieved 28 Julie 2013.

- ↑ "ФСО доложила о межконфессиональных отношениях в РФ". ZNAK. Archived frae the original on 16 Apryle 2017. Retrieved 15 Apryle 2017.

- ↑ "The 2013 Census and religion" (PDF). royalsociety.org.nz. Archived (PDF) frae the original on 28 Februar 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ↑ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Buddhists". teara.govt.nz. Archived frae the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 12 Juin 2020.

- ↑ "Buddhist Channel | Buddhism News, Headlines | World | Burmese Buddhist monastery opens in Finland". Buddhistchannel.tv. 5 Januar 2009. Archived frae the original on 28 Apryle 2021. Retrieved 9 Apryle 2021.

- Trainor, Kevin; Arai, Paula, eds. (2022). The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Practice (in Inglis). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063295-3. Archived frae the original on 29 Mey 2022. Retrieved 12 Juin 2022.

- Trainor, Kevin; Arai, Paula, eds. (2022). The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Practice (in Inglis). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063295-3. Archived frae the original on 29 Mey 2022. Retrieved 12 Juin 2022.

- Trainor, Kevin; Arai, Paula, eds. (2022). The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Practice (in Inglis). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063295-3. Archived frae the original on 29 Mey 2022. Retrieved 12 Juin 2022.

External links

[eedit | eedit soorce]- Worldwide Buddhist Information and Education Network, BuddhaNet

- Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral

- East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, Robert Buswell an William Bodiford, UCLA

- Buddhist Bibliography (China and Tibet), East West Center

- Ten Philosophical Questions: Buddhism, Richard Hayes, Leiden University

- Readings in Theravada Buddhism, Access to Insight

- Readings in Zen Buddhism, Hakuin Ekaku (Ed: Monika Bincsik)

- Readings in Sanskrit Buddhist Canon, Nagarjuna Institute – UWest

- Readings in Buddhism, Vipassana Research Institute (English, Southeast Asian and Indian Languages)

- Religion and Spirituality: Buddhism at Open Directory Project

- The Future of Buddhism series, fæ Patheos

- Buddhist Art, Smithsonian

- Buddhism – objects, art and history, V&A Museum

- Buddhism for Beginners, Tricycle

[[Category:Indie releegions]]

[[Category:Buddhism]]

[[Category:Webarchive template wayback airtins]]

[[Category:CS1: abbreviated year range]]

[[Category:CS1: lang volume vailyie]]

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "web", but no corresponding <references group="web"/> tag was found