Early Modren Inglis

| Early Modren Inglis | |

|---|---|

| Shakespeare's Inglis, Keeng James Inglis | |

| English | |

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 132 in the 1609 Quarto | |

| Region | Ingland, southern Scotland, Ireland, Wales and British colonies |

| Era | developed into Modren Inglis in late 17th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Leid codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | emen |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | en-emodeng |

Early Modren Inglis or Early New Inglis is the stage o the Inglis leid frae the beginnin o the Tudor period tae the Inglis Interregnum an Restoration, or frae the transeetion frae Middle Inglis, in the late 15t century, tae the transeetion tae Modren Inglis, in the mid-tae-late 17t century.[1]

Afore an efter the accession o James I tae the Inglis throne in 1603, the kythin Inglis staundard began tae moyen the spoken an written Middle Scots o Scotland.

The grammatical an orthographical pratticks o leeterar Inglis in the late 16t century an in the 17t century are aye muckle big pairts o Modren Staundard Inglis. Some modren readers o Inglis can unnerstaund gruns written in the late phase o the Early Modren Inglis, sic as the Keeng James Bible an the warks o William Shakespeare, an they hae greatly moyened Modren Inglis.

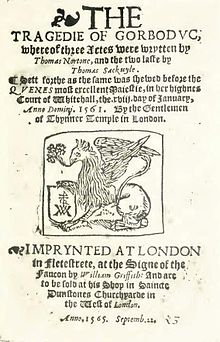

Gruns frae the earlier phase o Middle Inglis, sic as the late-15t century Le Morte d'Arthur (1485) an the mid-16t century Gorboduc (1561), mey be maire difficult for modren readers but are aye obviously closer tae Modren Inglis grammar, lexicon an phonology than are 14t-century Middle Inglis gruns, sic as the warks o Geoffrey Chaucer.

History

[eedit | eedit soorce]Inglis Renaissance

[eedit | eedit soorce]Transeetion frae Middle Inglis

[eedit | eedit soorce]The change frae Middle Inglis tae Early Modren Inglis wisna juist the changes tae vocables or pronunciation; a new era in the history o Inglis wis beginnin.

An era o linguistic change in a leid wi lairge variorums in deealect wis replaced bi a new era o a maire staundardised leid, wi a richer lexicon an an estaiblisht (an lestie) leeteratur.

- 1476 – William Caxton stairts prenting in Westminster; houaniver, the leid that he uises reflects the variety o styles an deealects uised bi the authors wha oreeginally wrat the material.

Tudor period (1485–1603)

[eedit | eedit soorce]- 1485 – Caxton publeeshes Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, the first prent bestseller in Inglis. Malory's leid, while archaic in some weys, is clearly Early Modren an is possibly a Yorkshire or Midlands deealect.

- 1491 or 1492 – Richard Pynson stairts prenting in Lunnon; his style tents tae prefer Chancery Standard, the form o Inglis uised bi the government.

Henry VIII

[eedit | eedit soorce]- c. 1509 – Pynson becomes the King's offeecial prenter.

- Frae 1525 – Ootset o William Tyndale's Bible translation, whit wis ineetially banned.

- 1539 – Ootset o the Great Bible, the first offeecially-authorised Bible in Inglis. Eedited bi Myles Coverdale, it is lairgely frae the wark o Tyndale. It is rade tae congregations regularly in kirks, whit fameeliarises muckle o the population o Ingland wi a standard form o the leid.

- 1549 – Ootset o the first Book o Common Prayer in Inglis, owerseen bi Thomas Cranmer (revised 1552 an 1662), whit standardises muckle o the wirding o kirk services. Some hae argued that since attendance at prayer beuk services wis required bi law for mony years, the repetitive uise o its leid helped tae standardise Modren Inglis even maire than the Keeng James Bible (1611) did.[2]

- 1557 – Ootset o Tottel's Miscellany.

Elizabethan Inglis

[eedit | eedit soorce]

- Elizabethan era (1558–1603)

- 1582 – The Rheims an Douai Bible is feenished, an the New Testament is released in Reims, Fraunce, in 1582. It is the first feenished Inglis translation o the Bible that is offeecially sponsored an carried oot bi the Catholic Kirk (earlier translations intae Inglis, espeicially o the Psalms an Gospels existed as far back as the 9t century, but it is the first Catholic Inglis translation o the fou Bible). Tho the Auld Testament is feenished earlier, it is no publeeshed till 1609–1610, whan it is released in twa vollums. It daesna mak a lairge dint on the Inglis leid at lairge, it shuirly plays a role in the development o Inglis, espeicially in the warld's hivily-Catholic Inglis-speakin airies.

- Christopher Marlowe, fl. 1586–1593

- 1592 – The Spanish Tragedy bi Thomas Kyd

- c. 1590 tae c. 1612 – Shakespeare's plays written.

17t century

[eedit | eedit soorce]Jacobean an Caroline eras

[eedit | eedit soorce]Jacobean era (1603–1625)

[eedit | eedit soorce]- 1609 – Shakespeare's sonnets publeeshed

- Ither playwrights:

- 1607 – The first thrivin permanent Inglis colony in the New Warld, Jamestown, is estaiblished in Virginie. Early vocable specific tae American Inglis cams frae indigenous leids (sic as moose, racoon).

- 1611 – The Keeng James Bible is publeeshed, lairgely based on Tyndale's translation. It remeens the staundar Bible in the Kirk o Ingland for mony years.

- 1623 – Shakespeare's First Folio publeeshed

Caroline era an Inglis Ceevil War (1625–1649)

[eedit | eedit soorce]- 1630–1651 – William Bradford, Governor o Plymouth Colony, writes in his jurnal. It will become Of Plymouth Plantation, ane o the earliest gruns written in the American Colonies.

- 1647 – Ootset o the first Beaumont an Fletcher folio.

Interregnum an Restoration

[eedit | eedit soorce]The Inglis Ceevil War an the Interregnum war times o social an poleetical upheaval an instabeelity. The dates for Restoration leeteratur are a matter o prattick an differ merkitly frae genre tae genre. In drama, the "Restoration" mey lest till 1700, but in poetry, it mey lest anely till 1666, the annus mirabilis (year o wunners), an prose, it lest till 1688, wi the increasing tensions ower succession an the confeerin rise in jurnalism an periodicals, or till 1700, whan thae periodicals growed maire stabilised.

- 1651 – Ootset o Leviathan bi Thomas Hobbes.

- 1660–1669 – Samuel Pepys writes in his diary, whit will become an important eewitness account o the Restoration Era.

- 1662 – New edeetion o the Book o Common Prayer, lairgely based on the 1549 an later edeetions, whit lang remeens a staundar wark in Inglis.

- 1667 – Ootset o Paradise Lost bi John Milton an o Annus Mirabilis bi John Dryden.

Development tae Modren Inglis

[eedit | eedit soorce]The 17t-century port touns an their forms o speech gain moyen ower the auld coonty touns. Ingland experiences a new period o inner peace an relative stability, whit encourages the airts incluiding leeteratur, frae arouod the 1690s onwards.

Modren Inglis can be takken tae hae kythed fou bi the beginnin o the Georgian era in 1714, but Inglis orthography remeened somewhit bree till the ootset o Johnson's Dictionary, in 1755.

The tourin importance o William Shakespeare ower the ither Elizabethan authors wis the result o his reception durin the 17t an the 18t centuries, whit direct contreebutes tae the development o Staundard Inglis[citation needit]. Shakespeare's plays are tharefore aye fameeliar an unnerstaundable 400 years efter they war written,[3] but the warks o Geoffrey Chaucer an William Langland, whit haed been written anely 200 years earlier, are conseederably maire difficult for the common five aichts modren reader.

Orthography

[eedit | eedit soorce]

The orthography o Early Modren Inglis wis fair seemilar tae that o the day, but spelling wis unstable. Early Modren Inglis, as well as Modren Inglis, inherited orthographical pratticks predating the Great Vouel Shift.

Early Modren Inglis spelling wis seemilar tae that o Middle Inglis. Certaint changes war made, houaniver, sometimes for raisons o etymology (as wi the seelent ⟨b⟩ that wis added tae wirds like debt, doubt an subtle).

Early Modren Inglis orthography haed a nummer o featurs o spelling that hivna been reteened:

- The letter ⟨S⟩ haed twa perqueer lawercase forms: ⟨s⟩ (short s), as is aye uised the day, an ⟨ſ⟩ (lang s). The short' s wis the aye uised at the end o a wird an aft elsewhaur. The lang s, if uised, coud appear onywhaur except at the end o a wird. The dooble lawercase S wis written variously ⟨ſſ⟩, ⟨ſs⟩ or ⟨ß⟩ (the feenal ligature is aye uised in German ß).[4] That is seemilar tae the alternation atween medial (σ) an feenal lawer case sigma (ς) in Greek.

- ⟨u⟩ an ⟨v⟩ war then conseedered as no twa perqueer letters but as aye different forms o the same letter. Typographically, ⟨v⟩ wis frequent at the stairt o a wird an ⟨u⟩ elsewhaur:[5] hyne vnmoued (for modren unmoved) an loue (for love). The modren prattick o uisin Template:Vr for the vouel soond(s) an Template:Vr for the consonant appears tae hae been introduced in the 1630s.[6] Awso, ⟨w⟩ wis frequently represented bi ⟨vv⟩.

- Seemilarly, ⟨i⟩ an ⟨j⟩ war awso aye conseedered no as twa perqueer letters, but as different forms o the same letter: hyne ioy for joy an iust for juist. Again, the custom o uisin Template:Vr as a vouel an Template:Vr as a consonant began in the 1630s.[6]

- The letter ⟨þ⟩ (thorn) wis aye in uise durin the Early Modren Inglis period but wis increasingly leemitit tae haundwritten gruns. In Early Modren Inglis prenting, ⟨þ⟩ wis represented bi the Latin ⟨Y⟩ (see Ye olde), whit appeared seemilar tae thorn in blackletter typeface ⟨𝖞⟩. Thorn haed become near halely disuised bi the late Early Modren Inglis period, the feenal signacles o the letter bein its ligatures, ye (thee), yt (that), yu (thou), whit war aye seen occasionally in the 1611 Keeng James Bible an in Shakespeare's Folios.[5]

- A seelent ⟨e⟩ wis aft appended tae wirds, as in ſpeake an cowarde. The feenal consonant wis sometimes doobled whan the ⟨e⟩ wis added: hyne manne (for man) an runne (for run).

- The soond /ʌ/ wis aft written ⟨o⟩ (as in son): hyne ſommer, plombe (for modren summer, plumb).[7]

- The feenal syllable o wirds like public wis variously spelt but cam tae be staundarised as -ick. The modren spellings wi -ic daedna come intae uise till the mid-18t century.[8]

Mony spellings haed aye no been staundarised, houaniver. For ensaumple, he wis spelt as baith he an hee in the same sentence in Shakespeare's plays an elsewhaur.

Phonology

[eedit | eedit soorce]Consonants

[eedit | eedit soorce]Maist consonant soonds o Early Modren Inglis hae survived intae present-day Inglis; houaniver, thare are aye a few merkit differs in pronunciation:

- The day's "seelent" consonants fund in the consonant clusters o sic wirds as knot, gnat, sword war aye fou pronounced up till the mid-tae-late 16t century an thus presumably bi Shakespeare, tho they war fou reduced bi the early 17t century.[9] The digraph <ght>, in wirds like night, thought, an daughter, originally pronounced [xt] in much aulder Inglis, wis probably reduced tae simply [t] (as it is the day) or at least heavily reduced in soond tae something like [ht], [çt], or [ft]. It seems likely that much variation existed for mony o these wirds.

- The now-seelent l o would an should mey hae persisted in being pronounced as late as 1700 in Britain an aiblins several decades langer in the Breetish American colonies.[10]

- The modren phoneme /ʒ/ wisna writ as occurring till the seicond half o the 17th century. Likely, that phoneme in a wird like vision wis pronounced as /zi/ an in measure as /z/.

- Maist wirds wi the spelling ⟨wh⟩, sic as what, where, an whale, war aye pronounced [ʍ], raither than [w]. That means, for example, that wine an whine war aye pronounced differently, unlike in maist varieties o Inglis the day.[11]

- Early Modren Inglis wis rhotic. In ither wirds, the r wis aye pronounced,[11] but the preceese naitur o the teepical rhotic consonant remeens unclear. [citation needit] It wis, houaniver, shuirly ane o the following:

- In Early Modren Inglis, the preceese naitur o the licht an daurk variants o the l consonant, respectively [l] an [ɫ], remeens unclear.

- Wird-final ⟨ng⟩, as in sing, wis aye pronounced /ŋɡ/ till the late 16t century, whan it began tae coalesce intae the usual modren pronunciation, [ŋ].

- H-dropping at the stairt o wirds wis common, as it aye is in informal Inglis throughout maist o Ingland.[11]

Pure vouels an diphthongs

[eedit | eedit soorce]The following information primarily comes frae studies o the Great Vouel Shift;[12] see the related chart.

- The modren Inglis phoneme /aɪ/, as in glide, rhyme, an eye, wis [ɘi] an later [əi]. Early Modren rhymes shaw that [əi] wis awso the vouel that wis uised at the end o wirds like happy, melody an busy.

- /aʊ/, as in now, out an ploughed, wis [əu ~ əʊ] (

listen).

listen). - /æ/, as in cab, trap an sad, wis maire or less the same as the phoneme represents the day.

- /ɛ/, as in fed, elm, an hen, wis maire or less the same as the phoneme represents the day or aiblins a slightly higher [ɛ̝], sometimes approaching [ɪ] (as it aye retains in the wird pretty).[11]

- /eɪ/, as in name, case an sake, wis a lang monophthong, approximating [ɛː], aiblins at first maire open, sic as /æ/ (wi Shakespeare rhyming wirds like haste, taste an waste wi a fronted last an shade wi sad),[13] an later less open, sic as [ɛ̝ː]. The phoneme wis juist beginnin or aye in the process o merging wi the phoneme [ɛːi] (

listen) as in day, pay, an say. Depending upon the exact moment or deealect o Early Modren Inglis, met wis a potential homophone wi mate; the same wis true for even mat an mate. Sic an open pronunciation remeens in some deealects, notably in Scotland, Northern Ingland, an aiblins Ireland.

listen) as in day, pay, an say. Depending upon the exact moment or deealect o Early Modren Inglis, met wis a potential homophone wi mate; the same wis true for even mat an mate. Sic an open pronunciation remeens in some deealects, notably in Scotland, Northern Ingland, an aiblins Ireland. - /iː/ (teepically spellt ⟨ee⟩ or ⟨ie⟩) as in see, bee an meet, wis maire or less the same as the phoneme represents the day, but it haedna yet merged wi the phoneme represented bi the spellings ⟨ea⟩ or ⟨ei⟩ (an aiblins ⟨ie⟩, particularly wi fiend, field an friend), as in east, meal an feat, whit war pronounced wi [eː] or [ɛ̝ː].[13][14] Houaniver, wirds like breath, dead an head mey hae aye split aff towards /ɛ/).

- /ɪ/, as in bib, pin an thick, wis maire or less the same as the phoneme represents the day.

- /oʊ/, as in stone, bode an yolk, wis [oː] or [o̞ː]. The phoneme wis probably juist beginnin the process o merging wi the phoneme [ou], as in grow, know an mow, without yet achieving the day's complete merger. The auld pronunciation remeens in some deealects, sic as in Yorkshire an Scotland.

- /ɒ/, as in rod, top an pot, wis [ɒ] or [ɔ].

- /ɔː/, as in taut, taught an law, wis [ɔː] or [ɑː].

- /ɔɪ/, as in boy, choice an toy, is even less clear than ither vouels. Bi the late-16t century, the similar but distinct phonemes /ɔɪ/, /ʊi/ and /əɪ/ aw existed. Bi the late-17th century, anely /ɔɪ/ remeened.[5] Acause those phonemes war in sic a state o flux durin the whale Early Modren period (wi evidence o rhyming occurring among them as well as wi the precursor tae /aɪ/), scholars[9] aft assume anely the maist neutral possibility for the pronunciation o /ɔɪ/ as well as its similar phonemes in Early Modren Inglis: [əɪ] (whit, if accurate, would constitute an early instance o the line–loin merger since /aɪ/ haedna yet fou developed in Inglis).

- /ʌ/ (as in drum, enough an love) an /ʊ/ (as in could, full, put) haedna yet split an so war baith pronounced in the vicinity o [ɤ].

- /uː/ wis aboot the same as the phoneme represents the day but occurred in no anely wirds like food, moon an stool but awso aw ither wirds spelt wi ⟨oo⟩ like blood, cook an foot. The naitur o the vouel soond in the latter group o wirds, houaniver, is further complicated bi the fact that the vouel for some o those wirds wis shortened: either beginnin or aye in the process o approximating the Early Modren Inglis [ɤ] an later [ʊ]. For instance, at certain stages o the Early Modren period or in certain deealects (or baith), doom an come rhymed; this is shuirly true in Shakespeare's writing. That phonological split among the ⟨oo⟩ wirds wis a catalyst for the later foot–strut split an is cawed "early shortening" bi John C. Wells.[5] The ⟨oo⟩ wirds that war pronounced as something like [ɤ] seem tae hae included blood, brood, doom, good an noon.[15]

- /ɪʊ̯/ or /iu̯/ occurred in wirds spelt wi ew or ue sic as due an dew. In maist deealects o Modren Inglis, it became /juː/ an /uː/ bi yod-dropping an so do, dew an due are now perfect homophones. A distinction atween the twa phonemes remeens in Wales an in ither conservative deealects.

Rhotic vouels

[eedit | eedit soorce]It is clear that the r soond (the phoneme /r/) wis probably aye pronounced wi following vouel soonds (maire in the style o the day's Wastern Inglis, Norfolk, Northern Inglis, Irish or Scots accents, an less like the day's teepical Lunnon or Received Pronunciation). Furthermore, /ɛ/, /ɪ/ and /ʌ/ warna necessarily merged afore /r/, as they are in maist modren Inglis deealects. The stressed modren phoneme /ɜːr/, whan it is spelt ⟨er⟩, ⟨ear⟩ an aiblins ⟨or⟩ (as in clerk, earth, or divert), haed a vouel soond wi an a-like quality, aiblins aboot [ɐɹ] or [äɹ].[13] Wi the spelling ⟨or⟩, the soond mey hae been backed, maire toward [ɒɹ] in wirds like worth an word.[13] In some pronunciations, wirds like fair an fear, wi the spellings ⟨air⟩ an ⟨ear⟩, rhymed wi ilk ither, an wirds wi the spelling ⟨are⟩, sic as prepare an compare, war sometimes pronounced wi a maire open vouel soond, like the verbs are an scar. See Great Vowel Shift § Later mergers for maire information.

Particular wirds

[eedit | eedit soorce]Nature wis pronounced approximately as [ˈnɛːtəɹ] [11] an mey hae ryhmed wi letter or, early on, even latter. One mey hae merged tae the soond o own, wi baith one an other uising the era's lang GOAT vouel, raither than the day's STRUT vouels.[11] Tongue merged tae the soond o tong an rhymed wi song.[13]

Grammar

[eedit | eedit soorce]Pronouns

[eedit | eedit soorce]Early Modren Inglis haed twa seicond-person personal pronouns: thou, the informal singular pronoun, an ye, the plural (baith formal an informal) pronoun an the formal singular pronoun.

"Thou" an "ye" war baith common in the early-16t century (they can be seen, for example, in the disputes ower Tyndale's translation o the Bible in the 1520s an the 1530s) but bi 1650,"thou" seems auld-fashioned or literary.[citation needit] It hae effectively completely disappeared frae Modren Staundard Inglis but is aye in use in some situations. In mony kirks in the Unitit Kinrick an the Unitit States, primarily those that uise the King James Bible, "thou" is aye uised tae address God in prayer an is felt tae denote reverence. "Thou" awso remains in regular uise in particular regional Inglis dialects, but its pronunciation is aft reduced tae "tha".[citation needit]

The translators o the Keeng James Bible o the Bible (begun 1604 an published 1611, while Shakespeare wis at the heicht o his popularity) haed a particular reason for keeping the "thou/thee/thy/thine" forms that war slowly beginnin tae fa oot o spoken uise, as it enabled them tae match the Hebrew an Ancient Greek distinction atween seicond person singular ("thou") an plural ("ye"). It wisna tae denote reverence (in the King James Bible, God addresses individual people an even Satan as "thou") but anely tae denote the singular. Ower the centuries, however, the very fact that "thou" wis dropping oot o normal uise gave it a special aura an so it gradually cam tae be uised tae express reverence in hymns an in prayers.[citation needit]

Like ither personal pronouns, thou an ye have different forms dependent on their grammatical case; specifically, the objective form o thou is thee, its possessive forms are thy an thine, an its reflexive or emphatic form is thyself.

The objective form o ye wis you, its possessive forms are your an yours an its reflexive or emphatic forms are yourself an yourselves.

My an thy become mine an thine before wirds beginnin with a vowel or an h. More accurately, the aulder forms "mine" an "thine" haed become "my" an "thy" before wirds beginnin with a consonant ither than h, an "mine" an "thine" war retained before wirds beginnin with a vowel or an h, as in mine eyes or thine hand.

| Nominative | Oblique | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | I | me | my/mine[# 1] | mine |

| plural | we | us | our | ours | |

| 2nd person | singular informal | thou | thee | thy/thine[# 1] | thine |

| plural or formal singular | ye, you | you | your | yours | |

| 3rd person | singular | he/she/it | him/her/it | his/her/his (it)[# 2] | his/hers/his[# 2] |

| plural | they | them | their | theirs | |

- ↑ a b The genitives my, mine, thy, and thine are used as possessive adjectives before a noun, or as possessive pronouns without a noun.

- ↑ a b From the early Early Modern English period up until the 17th century, his was the possessive of the third-person neuter it as well as of the third-person masculine he.

Verbs

[eedit | eedit soorce]Tense an nummer

[eedit | eedit soorce]Durin the Early Modren period, the verb inflections became simplified as they evolved towards their modren forms:

- The third-person singular present lost its alternate inflections: -(e)th became obsolete, an -s survived. (Baith forms can be seen thegither in Shakespeare: "With her, that hateth thee and hates us all").[5]

- The plural present form became uninflected. Present plurals haed been merkit wi -en an singulars wi -th or -s (-th an -s survived the langest, especially wi the singular uise o is, hath an doth).[5] Merkit present plurals war rare throughout the Early Modren period an -en wis probably uised anely as a stylistic affectation tae indicate rural or auld-fashioned speech.[5]

- The seicond-person singular indicative wis merkit in baith the present an past tenses wi -st or -est (for example, in the past tense, walkedst or gav'st).[5] Since the indicative past wisna an aye isna otherwise merkit for person or nummer,[5] the loss o thou made the past subjunctive indistinguishable frae the indicative past for aw verbs except to be.

Modal auxiliaries

[eedit | eedit soorce]The modal auxiliaries cemented their distinctive syntactical characteristics durin the Early Modren period. Thus, the uise o modals without an infinitive became rare (as in "I must to Coventry"; "I'll none of that"). The uise o modals' present participles tae indicate aspect (as in "Maeyinge suffer no more the loue & deathe of Aurelio" frae 1556), an o their preterite forms tae indicate tense (as in "he follow'd Horace so very close, that of necessity he must fall with him") awso became uncommon.[5]

Some verbs ceased tae function as modals durin the Early Modren period. The present form o must, mot, became obsolete. Dare awso lost the syntactical characteristics o a modal auxiliary an evolved a new past form (dared), distinct frae the modal durst.[5]

Perfect an progressive forms

[eedit | eedit soorce]The perfect o the verbs haedna yet been staundardised tae uise anely the auxiliary verb "to have". Some took as their auxiliary verb "to be", sic as this example frae the King James Bible: "But which of you... will say unto him... when he is come frae the field, Go and sit down..." [Luke XVII:7]. The rules for the auxiliaries for different verbs war similar tae those that are aye observed in German an French (see unaccusative verb).

The modren syntax uised for the progressive aspect ("I am walking") became dominant bi the end o the Early Modren period, but ither forms war awso common sic as the prefix a- ("I am a-walking") an the infinitive paired wi "do" ("I do walk"). Moreover, the to be + -ing verb form could be uised tae express a passive meaning without ony additional merkers: "The house is building" could mean "The house is being built".[5]

Vocabulary

[eedit | eedit soorce]A nummer o wirds that are aye in common uise in Modren Inglis have undergone semantic narrowing.

The uise o the verb "to suffer" in the sense o "to allow" survived intae Early Modren Inglis, as in the phrase "suffer the little children" o the King James Bible, but it haes maistly been lost in Modren Inglis.[16]

Awso, this period reveals a curious case o ane o the earliest Russian borrowings tae Inglis (which is historically a rare occasion itself, either research sources are yet scarce[17]), in example – at least as early as year 1600, the wird "steppe" (rus. степь),[18] that haes first appeared in Inglis in William Shakespeare's comedy "A Midsummer Night's Dream". It is believed that this is a possible indirect borrowing via either German or French.

See also

[eedit | eedit soorce]- Early modren Britain

- Early Modren Inglis leeteratur

- History o the Inglis leid

- Inkhorn debate

- Elizabethan era, Jacobean era, Caroline era

- Inglis Renaissance

- Shakespeare's influence

- Middle Inglis, Modren Inglis, Auld Inglis

References

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ Nevalainen, Terttu (2006). An Introduction to Early Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- ↑ Stephen L. White, "The Book of Common Prayer and the Standardization of the English Language" The Anglican, 32:2(4-11), April, 2003

- ↑ Cercignani, Fausto, Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1981.

- ↑ Empty citation (help) Introduction uses both happineſs and bleſſedneſs.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Empty citation (help)

- ↑ a b Salmon, V., (in) Lass, R. (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, Vol. III, CUP 2000, p. 39.

- ↑ W.W. Skeat, in Principles of English Etymology, claims that the substitution was encouraged by the ambiguity between u and n; if sunne could just as easily be misread as sunue or suvne, it made sense to write it as sonne. (Skeat, Principles of English Etymology, Second Series. Clarendon Press, 1891, page 99.)

- ↑ Fischer, A., Schneider, P., "The dramatick disappearance of the Template:Vr spelling", in Text Types and Corpora, Gunter Narr Verlag, 2002, pp. 139ff.

- ↑ a b See The History of English (online) as well as David Crystal's Original Pronunciation (online).

- ↑ The American Language 2nd ed. p. 71

- ↑ a b c d e f Crystal, David. "Hark, hark, what shout is that?" Around the Globe 31. [based on article written for the Troilus programme, Shakespeare's Globe, August 2005: 'Saying it like it was'

- ↑ Stemmler, Theo. Die Entwicklung der englischen Haupttonvokale: eine Übersicht in Tabellenform [Trans: The development of the English primary-stressed-vowels: an overview in table form] (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1965).

- ↑ a b c d e Crystal, David (2011). "Sounding out Shakespeare: Sonnet Rhymes in Original Pronunciation Archived 2017-10-20 at the Wayback Machine". In Vera Vasic (ed.) Jezik u Upotrebi: primenjena lingvsitikja u cast Ranku Bugarskom. Novi Sad and Belgrade: Philosophy faculties. P. 298-300.

- ↑ Cercignani, Fausto (1981), Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Crystal, David. "Sounding Out Shakespeare: Sonnet Rhymes in Original Pronunciation". In Vera Vasic (ed.), Jezik u upotrebi: primenjena lingvistikja u cast Ranku Bugarskom [Language in use: applied linguistics in honour of Ranko Bugarski] (Novi Sad and Belgrade: Philosophy Faculties, 2011), 295-306300. p. 300.

- ↑ Doughlas Harper, https://www.etymonline.com/word/suffer#etymonline_v_22311

- ↑ Mirosława Podhajecka Russian borrowings in English: A dictionary and corpus study, p.19

- ↑ Max Vasmer, Etymological dictionary of the Russian language

External links

[eedit | eedit soorce]- Inglis Paleography Archived 2010-06-16 at the Wayback Machine: Examples for the study o Inglis handwriting frae the 16t–18t centuries frae the Beinecke Rare Book an Manuscript Library at Yale Varsity