Reid tod

The "Scots" that wis uised in this airticle wis written bi a body that haesna a guid grip on the leid. Please mak this airticle mair better gin ye can. (September 2020) |

| Reid tod | |

|---|---|

| |

European reid tod (V. v. crucigera) photographed at the Breetish Wildlife Centre in Surrey, Ingland. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kinrick: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Cless: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Faimily: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Vulpes |

| Species: | V. vulpes |

| Binomial name | |

| Vulpes vulpes | |

| Subspeshies | |

| |

| Distribution o the reid tod native

inbrocht presence uncertaint | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The reid tod (Vulpes vulpes) is a mammal o the order Carnivora. Reid tods is the maist muckle species o tod in the warld, an the maist kenspeckle species o tod. Thay'r hamelt tae Europe, the muckle feck o Aisie but Sootheast Aisie, northren Africae an the muckle feck o North Americae. Reid tods haes been inbrocht tae Austrailie, whaur thay're an invasive species.

Thare's 45 subspecies o reid tod.

Description

[eedit | eedit soorce]

The reid tod haes an elangatit bouk an relatively short limms. The tail, that is langer than hauf the bouk lenth[3] (70 per cent o heid an body lenth),[4] is fluffy an reaches the grund when in a staundin poseetion. Thair pupils are oval an vertically oriented.[3] Nictitating membranes are present, but muive anly when the een are closed. The forepaws hae five deegits, while the hint feet hae anly fower an lack dewclaws.[5] Thay are very agile, bein capable o jimpin ower 2-metre-high (6 ft 7 in) fences, an soum well.[6] Vixens normally hae fower pairs o teats,[3] tho vixens wi seiven, nine, or ten teats are nae uncommon.[5] The testes o males are smawer than thae o Arctic tods.[3]

Thair skults are fairly narrow an elangatit, wi smaw braincases. Thair canine teeth are relatively lang. Sexual dimorphism o the skult is mair pronoonced than in corsac tods, wi female reid tods tendin tae hae smawer skults than males, wi wider nasal regions an haurd palates, as well as haein lairger canines.[3] Thair skults are distinguished frae thae o dugs bi thair narraer muzzles, less croudit premolars, mair slender canine teeth, an concave raither than convex profiles.[5]

Dimensions

[eedit | eedit soorce]Reid tods are the lairgest species o the genus Vulpes.[7] Houiver, relative tae dimensions, reid tods are much lighter than similarly sized dogs o the genus Canis. Thair limm banes, for ensaumple, wecht 30 percent less per unit aurie o bane than expected for similarly sized dogs.[8] Thay display significant individual, sexual, age an geographical variation in size. On average, adults meisur 35–50 cm (14–20 in) heich at the shouder an 45–90 cm (18–35 in) in body lenth wi tails meisurin 30–55.5 cm (11.8–21.9 in). The lugs meisur 7.7–12.5 cm (3–5 in) an the hint feet 12–18.5 cm (5–7 in). Weights range frae 2.2–14 kg (5–31 lb), wi vixens teepically weighin 15–20% less nor males.[9][10] Adult reid tods hae skults meisurin 129–167 mm (5.1–6.6 in), while thae o vixens meisur 128–159 mm (5.0–6.3 in).[3] The forefoot prent measures 60 mm (2.4 in) in lenth an 45 mm (1.8 in) in weenth, while the hint fit prent measures 55 mm (2.2 in) lang an 38 mm (1.5 in) wide. Thay trot at a speed o 6–13 km/h (4–8 mph), an hae a maximum runnin speed o 50 km/h (30 mph). Thay hae a stride o 25–35 cm (9.8–13.8 in) when walkin at a normal pace.[8]:36 North American reid tods are generally lightly biggit, wi comparatively lang bodies for thair mass an hae a heich degree o sexual dimorphism. British reid tods are heavily biggit, but short, while continental European reid tods are closer tae the general average amang reid tod populations.[11] The lairgest reid tod on record in Great Britain wis a 17.2 kg (38 lb), 1.4-metre (4 ft 7 in) lang male, killed in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, in early 2012.[12]

Fur

[eedit | eedit soorce]The winter fur is dense, saft, silky an relatively lang. For the northren tods, the fur is verra lang, dense an fluffy, but is shorter, sparser an coarser in soothren forms.[3] Amang northren tods, the North American varieties generally hae the silkiest guard hairs,[13]:231 while maist Eurasian reid tods hae coarser fur.[13]:235 Thare are three main colour morphs; reid, siller/black an cross (see Mutations).[4] In the teepical reid morph, thair coats are generally bricht reiddish-rusty wi yellowish tints. A stripe o waik, diffuse patterns o mony broun-reiddish-chestnut hairs occurs alang the spine. Twa additional stripes pass doun the shouder blades, which, thegither wi the spinal stripe, form a cross. The lawer back is eften a mottled sillery colour. The flanks are lighter coloured than the back, while the chin, lawer lips, throat an front o the chest are white. The remainin lawer surface o the bouk is daurk, broun or reiddish.[3] Durin lactation, the belly fur o vixens mey turn brick reid.[5] The upper pairts o the limms are rusty reiddish, while the paws are black. The frontal pairt o the face an upper neck is bricht brounish-rusty reid, while the upper lips are white. The backs o the lugs are black or brounish-reiddish, while the inner surface is whitish. The tap o the tail is brounish-reiddish, but lichter in colour than the back an flanks. The unnerside o the tail is pale grey wi a strae-coloured tint. A black spot, the location o the supracaudal gland, is uisually present at the base o the tail. The tip o the tail is white.[3]

Mutations

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Atypical colourations in reid tods uisually represent stages taewart fou melanism,[3] an maistly occur in cauld regions.[15]

| Colour variant | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reid |

|

The teepical colouration. See Fur |

| Grey | The rump an spine is broun or grey wi licht yellaeish baunds on the gaird hairs. The cross on the shouders is broun, rusty broun or brounish-reiddish. The limms are broun[3] | |

| Cross |

|

The fur haes a darker colouration tae the umwhile. The rump an lawer back are dark broun or dark grey, wi varyin degrees o siller on the guard hairs. The cross on the shouders is black or broun, whiles wi licht silvery fur. The feet an heid are broun[3] |

| Blackish-broun | The melanistic form o the Eurasian reid fox. Has blackish-broun or black skin wi a licht-brounish tint. The skin uisually haes an admixture o various amoonts o siller. Reiddish hairs are aither completely absent or in smaw quantities[3] | |

| Siller |

|

The melanistic form o the North American reid fox, but introduced tae the Auld Warld bi the fur tred. Chairacterised bi pure black colour wi a variable admixture o siller (coverin 25–100% o the skin aurie)[3] |

| Platinum |

|

Distinguished frae the siller morph bi its late pale, awmaist siller-white fur wi a bluish cast[13]:251 |

| Amber |

|

|

| Samson |

|

Distinguished bi its ooie pelt, which lacks guard hairs[13]:230 |

Senses

[eedit | eedit soorce]Reid tods hae binocular veesion,[5] but thair sicht reacts mainly tae muivement. Thair auditory perception is acute, bein able tae hear black grouse changin roosts at 600 paces, the flicht o craws at 0.25–0.5 kilometre (0.16–0.31 mi) an the squeakin o mice at aboot 100 metre (330 ft).[3] Thay are capable o locatin sounds tae within ane degree at 700–3,000 Hz, tho less accurately at higher frequencies.[6] Thair sense o smell is guid, but waiker than that o specialised dogs.[3]

Scent glands

[eedit | eedit soorce]Reid tods hae a pair o anal sacs lined bi sebaceous glands, baith o which open throu a single duct. The anal sacs act as fermentation chaumers in that aerobic an anaerobic bacteria convert sebum intae odorous compounds, includin aliphatic acids. The oval-shaped caudal gland is 25 mm (1.0 in) lang an 13 mm (0.51 in) wide, an reportedly smells o violets.[3] The presence o fit glands is equivocal. The interdigital cavities are deep, wi a reiddish tinge an smell strangly. Sebaceous glands are present on the angle o the jaw an mandible.[5]

Behaviour

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Social an territorial behaviour

[eedit | eedit soorce]Reid tods aither establish stable hame ranges within parteecular auries or are itinerant wi no fixed abode.[8]:117 Thay uise thair urine tae merk thair territories.[16] A male tod raises ane hint leg an his urine is sprayed forrit in front o him, whauras a female tod squats doun sae that the urine is sprayed in the grund atween the hint legs.[17] Urine is an aw uised tae merk emptie cache steids, uised tae store foond fuid, as reminders nae tae waste time investigatin them.[8]:125 [18][19] The uise o up tae 12 different urination posturs allous them tae precisely control the poseetion o the scent merk.[20] Reid tods live in faimily groups sharin a jynt territory. In favourable habitats an/or auries wi law huntin pressur, subordinate tods mey be present in a range. Subordinate tods mey nummer ane or twa, whiles up tae aicht in ane territory. Thir subordinates coud be umwhile dominant ainimals, but are maistly young frae the previous year, that act as helpers in rearin the breedin vixen's kits. Alternatively, thair presence haes been explained as bein in response tae temporary surpluses o fuid unrelated tae assistin reproductive success. Non-breedin vixens will guard, play, gruim, provision an retrieve kits,[5] an ensaumple o kin selection. Reid tods mey leave thair families ance thay reach adultheid if the chances o winnin a territory o thair ain are heich. If nae, thay will stay wi thair paurents, at the cost o postponin thair ain reproduction.[8]:140–141

Reproduction an development

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Reid tods reproduce ance a year in ware. Twa month prior tae oestrus (teepically December), the reproductive organs o vixens chynge shape an size. Bi the time thay enter thair oestrus period, thair uterine horns dooble in size, an thair ovaries grow 1.5–2 times lairger. Sperm formation in males begins in August–September, wi the testicles attainin thair greatest wecht in December–Februar.[3] The vixen's oestrus period lasts three weeks,[5] durin which the dog-tods mate wi the vixens for several days, eften in burraes. The male's bulbus glandis enlairges durin copulation,[15] formin a copulatory tie which mey last for mair nor an oor.[5] The gestation period lasts 49–58 days.[3] Tho tods are lairgely monogamous,[21] DNA evidence frae ane population indicated lairge levels o polygyny, incest an mixed paternity litters.[5] Subordinate vixens mey acome pregnant, but uisually fail tae whelp, or hae thair kits killed postpartum bi aither the dominant female or ither subordinates.[5]

The average litter size conseests o fower tae sax kits, tho litters o up tae 13 kits hae occurred.[3] Lairge litters are teepical in auries whaur tod mortality is heich.[8]:93 Kits are born blind, deif an tuithless, wi daurk broun fluffy fur. At birth, thay wecht 56–110 g (2.0–3.9 oz) an meisur 14.5 cm (5.7 in) in body lenth an 7.5 cm (3.0 in) in tail lenth. At birth, thay are short-legged, lairge-heidit an hae braid chests.[3] Mothers remain wi the kits for 2–3 weeks, as thay are unable tae thermoregulate. Durin this period, the faithers or barren vixens feed the mithers.[5] Vixens are very protective o thair kits, an hae been kent tae even fecht off terriers in thair defence.[22]:21–22 If the mither dies afore the kits are independent, the faither taks ower as thair provider.[22]:13 The kits' een open efter 13–15 days, durin which time thair ear canals open an thair upper teeth erupt, wi the lawer teeth emergin 3–4 days later.[3] Thair een are initially blue, but chynge tae lammer at 4–5 weeks. Coat colour begins tae chynge at three weeks o age, whan the black ee streak appears. Bi ane month, reid an white patches are apparent on thair faces. Durin this time, thair lugs erect an thair muzzles elongate.[5] Kits begin tae leave thair dens an experiment wi solit fuid brocht bi thair parents at the age o 3–4 weeks. The lactation period lasts 6–7 weeks.[3] Thair ooie coats begin tae be coatit bi shiny guard hairs efter 8 weeks.[5] Bi the age o 3–4 month, the kits are lang-legged, narrow-chested an sinewy. Thay reach adult proportions at the age o 6–7 month.[3] Some vixens mey reach sexual maturity at the age o 9–10 month, sicweys bearin thair first litters at ane year o age.[3] In captivity, thair langevity can be as lang as 15 years, tho in the wild thay teepically dae nae survive past 5 years o age.[23]

Denning behaviour

[eedit | eedit soorce]

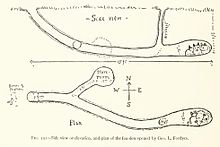

Ootside the breeding season, maist reid tods favour livin in the open, in densely vegetated auries, tho thay mey enter burraes tae escape bad wather.[5] Thair burraes are eften dug on hill or moontain slopes, ravines, bluffs, steep banks o watter bouks, ditches, depressions, gutters, in rock clefts an neglectur human environments. Reid tods prefer tae dig thair burraes on weel drained siles. Dens biggit amang tree ruits can last for decades, while thae dug on the steppes last anly several years.[3] Thay mey permanently abandon thair dens durin mange ootbreaks, possibly as a defence mechanism against the spreid o disease.[5] In the Eurasie desert regions, tods mey uise the burraes o woufs, porcupines an ither lairge mammals, as weel as thae dug bi gerbil colonies. Compared tae burraes biggit bi Arctic tods, badgers, marmots an corsac tods, reid tod dens are nae overly complex. Red tod burraes are dividit intae a den an temporary burraes, that conseest anly o a smaw passage or cave for concealment. The main entrance o the burrae leads dounwart (40–45°) an braidens intae a den, frae which numerous side tunnels brainch. Burrae deepth ranges frae 0.5–2.5 metre (1 ft 8 in–8 ft 2 in), rarely extendin tae grund watter. The main passage can reach 17 m (56 ft) in lenth, staundin an average o 5–7 m (16–23 ft). In spring, reid tods clear thair dens o excess sile throu rapid muivements, first wi the forepaws then wi kickin motions wi thair hint legs, throwin the discairdit sile ower 2 m (6 ft 7 in) frae the burrae. Whan kits are born, the discairdit debris is trampled, sicweys formin a spot whaur the kits can play an receive fuid.[3] Thay mey share thair dens wi woodchucks[15] or badgers.[3] Unlik badgers, that fastidiously clean thair yirds an defecate in latrines, reid tods habitually leave pieces o prey aroond thair dens.[22]:15–17> The average sleep time o a captive reid tod is 9.8 oors per day.[24]

Communication

[eedit | eedit soorce]Body language

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Red tod body leid conseests o movements o the lugs, tail an postures, wi thair body markings emphasisin certaint gestures. Postures can be dividit intae aggressive/dominant an fearful/submissive categories. Some postures mey blend the twa thegither.[8]:42–43

Inquisitive tods will rotate an flick thair lugs whilst sniffin. Playfu individuals will perk thair lugs an rise on thair hind legs. Male tods courtin females, or efter successfully evictin intruders, will turn thair lugs outwardly, an raise thair tails in a horizontal poseetion, wi the tips raised upward. When afraid, reid tods grin in submission, archin thair backs, curvin thair bouks, crouchin thair legs an lashin thair tails back an forth wi thair lugs pyntin backwards an pressed against thair skults. When merely expressin submission tae a dominant ainimal, the postur is seemilar, but wioot archin the back or curvin the bouk. Submissive tods will approach dominant ainimals in a law posture, sae that thair muzzles reach up in greetin. Whan twa evenly matched tods confront each ither ower fuid, thay approach each ither sideways an push against each ither's flanks, betrayin a mixture o fear an aggression throu lashin tails an arched backs wioot crouchin an pullin thair lugs back wioot flattenin them against thair skults. When launchin an assertive attack, reid tods approach directly rather than sideways, wi thair tails aloft an thair lugs rotated sideways.[8] Durin sic fechts, reid tods will staund on each ither's upper bodies wi thair forelegs, uisin open mouthed threats. Sic fights teepically anly occur amang juveniles or adults o the same sex.[5]

Vocalisations

[eedit | eedit soorce]Reid tods hae a wide vocal range, an produce different soonds spannin five octaves, which grade intae each ither.[8]:28 Recent analyses identify 12 different soonds produced bi adults an 8 bi kits.[5] The majority o sounds can be dividit intae "contact" an "interaction" calls. The umwhile vary accordin tae the distance atween individuals, while the latter vary accordin tae the level o aggression.[8]:28

- Contact calls: The maist commonly heard contact caw is a three tae five syllable berkin "wow wow wow" sound, which is eften made bi twa tods approachin ane anither. This caw is maist frequently heard frae December tae Februar (when thay can be confused wi the territorial calls o tawny ouls). The "wow wow wow" caw varies accordin tae individual; captive tods hae been recordit tae answer pre-recorded calls o thair pen-mates, but nae thae o strangers. Kits begin emittin the "wow wow wow" caw at the age o 19 days, when cravin attention. When reid tods draw close thegither, thay emit trisyllabic greetin warbles seemilar tae the cluckin o chickens. Adults greet thair kits wi gruff huffin noises.[8]:28

- Interaction calls: When greetin ane anither, reid tods emit heich pitched whines, parteecularly submissive ainimals. A submissive tod approached bi a dominant ainimal will emit a ululatin siren-lik shriek. Durin aggressive encounters wi conspecifics, thay emit a throaty rattlin sound, seemilar tae a ratchet, cried "gekkering". Gekkerin occurs maistly durin the courtin season frae rival males or vixens rejectin advances.[8]:28

Anither caw that daes nae fit intae the twa categories is a lang, drawn oot, monosyllabic "waaaaah" sound. As it is commonly heard durin the breedin saison, it is thocht tae be emittit bi vixens summonin males. When danger is detectit, tods emit a monosyllabic berk. At close quarters, it is a muffled coch, while at lang distances it is shairper. Kits mak warblin whimpers when nouricin, thir calls bein espeicially lood whan thay are dissatisfied.[8]:28

Ecology

[eedit | eedit soorce]Diet, huntin an feedin behaviour

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Reid tods are omnivores wi a heichly varied diet. Research conducted in the umwhile Soviet Union showed reid tods consuming ower 300 ainimal species an a few dozen species o plants.[3] Thay primarily feed on smaw rodents lik voles, mice, grund squirrels, hamsters, gerbils,[3] widchucks, pocket gophers an deer mice.[15] Seicontar prey species include birds (wi passeriformes, galliformes an watterfoul predominatin), leporids, porcupines, raccoons, opossums, reptiles, insects, ither invertebrates an flotsam (marine mammals, fish an echinoderms).[3][15] On very rare occasions, tods mey attack young or smaw ungulates.[3] Thay teepically target mammals up tae aboot 3.5 kg (7.7 lb) in wecht, an thay require 500 gram (18 oz) o fuid daily.[6] Reid tods readily eat plant material, an in some auries fruit can amoont tae 100% o thair diet in hairst. Commonly consumed fruits include blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, cherries, persimmons, mulberries, aiples, ploums, grapes, an aicorns. Ither plant material includes gresses, sedges an tubers.[15]

Reid tods are implicatit in the predation o gemme an sang birds, hares, rabbits, muskrats, an young ungulates, parteecularly in preserves, reserves, an huntin farms whaur grund nestin birds are pertectit an raised, as weel as in poutrie ferms.[3]

While the popular consensus is that olfaction is verra important for huntin,[25] twa studies that experimentally investigated the role o olfactory, auditory, an visual cues foond that visual cues are the maist important ones for huntin in reid tods[26] an coyotes.[27][28]

Reid tods prefer tae hunt in the early morn oors afore sunrise an late even.[3] Awtho thay teepically forage alone, thay mey aggregate in resoorce-rich environments.[23] When huntin moose-lik prey, thay first pinpynt thair prey's location bi soond, then leap, sailin heich abuin thair quarry, steerin in mid-air wi thair tails, afore laundin on target up tae 5 metre (16 ft) awey.[1] Thay teepically anly feed on carrion in the late even oors an at nicht.[3] Thay are extremely possessive o thair fuid an will defend thair catches frae even dominant ainimals.[8]:58 Reid tods mey occasionally commit acts o surplus killin; in ane breeding season, fower tods war recordit tae hae killed aroond 200 pirr-maws ilk, wi peaks during dark, windy oors when fleein conditions war unfavorable. Losses tae poultry an penned gemme birds can be substantial acause o this.[5][8]:164 Reid tods seem tae dislik the taste o moles but will nanetheless catch them alive an present them tae thair kits as playthings.[8]:41

A 2008–2010 study o 84 reid tods in the Czech Republic an Germany foond that successfu huntin in lang vegetation or unner snaw appeared tae involve an alignment o the tod wi the Yird's magnetic field.[29][30]

Enemies an competitors

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Reid tods teepically dominate ither tod species. Arctic tods generally escape competeetion frae reid tods bi leevin forder north, whaur fuid is too scarce tae support the lairger-bodied reid species. Awtho the reid species' northren leemit is linked tae the availability o fuid, the Arctic species' soothren range is leemitit bi the presence o the umwhile. Red an Arctic tods war baith introduced tae awmaist every island frae the Aleutian Islands tae the Alexander Archipelago during the 1830s–1930s bi fur companies. The reid tods invariably displaced the Arctic tods, wi ane male reid tod haein been reportit tae hae killed aff aw resident Arctic tods on a smaw island in 1866.[8] Whaur thay are sympatric, Arctic tods mey an aw escape competeetion bi feedin on lemmings an flotsam, rather than voles, as favoured bi reid tods. Baith species will kill ilk ither's kits, gien the opportunity.[3] Reid tods are serious competitors o corsac tods, as thay hunt the same prey aw year. The reid species is an aw stranger, is better adapted tae huntin in snaw deeper than 10 cm (4 in) an is mair effective in huntin an catching medium tae lairge-sized rodents. Corsac tods seem tae anly outcompete reid tods in semi-desert an steppe auries.[3][31] In Israel, Blanford's tods escape competeetion wi reid tods bi restricting themselves tae rocky cliffs an actively avoiding the open plains inhabited bi reid tods.[8]:84–85 Reid tods dominate kit an swift tods. Kit tods uisually avyde competeetion wi thair lairger cousins bi livin in mair arid environments, tho reid tods hae been increasin in ranges umwhile occupied bi kit tods due tae human-induced environmental changes. Reid tods will kill baith species, an compete for fuid an den sites.[15] Grey tods are exceptional, as thay dominate reid tods whauriver thair ranges meet. Historically, interactions atween the twa species war rare, as grey tods favoured hivily widdit or semiarid habitats as opponed tae the open an mesic ones preferred bi reid tods. Houiver, interactions hae acome mair frequent due tae deforestation allouin reid tods tae colonise grey tod-inhabitit auries.[15]

Woufs mey kill an eat reid tods in disputes ower carcasses.[3][32] In auries in North America whaur reid tod an coyote populations are sympatric, tod ranges tend tae be locatit ootside coyote territories. The principal cause o this separation is believed tae be active avoidance o coyotes bi the tods. Interactions atween the twa species vary in naitur, ranging frae active antagonism tae indifference. The majority o aggressive encounters are initiated bi coyotes, an thare are few reports o reid tods actin aggressively toward coyotes except when attacked or when thair kits war approached. Tods an coyotes hae whiles been seen feedin thegither.[33] In Israel, red tods share thair habitat wi golden jackals. Whaur thair ranges meet, the twa canids compete due tae near identical diets. Tods ignore jackal scents or tracks in thair territories, an avyde close physical proximity wi jackals themselves. In auries whaur jackals acome very abundant, the population o tods decreases significantly, apparently acause o competitive exclusion.[34]

Reid tods dominate raccoon dogs, whiles killin thair kits or bitin adults tae daith. Cases are kent o tods killin raccoon dogs entering thair dens. Baith species compete for mouse-lik prey. This competeetion reaches a peak during early spring, when fuid is scarce. In Tartaria, red tod predation accounted for 11.1% o daiths amang 54 raccoon dogs, an amounted tae 14.3% o 186 raccoon dog daiths in north-wastren Roushie.[3]

Reid tods mey kill smaw mustelids lik weasels,[15] stone martens,[35] pine martens, stoats, kolonoks, polecats an young sables. Eurasian badgers mey live alongside reid tods in isolated sections o lairge burrows.[3] It is possible that the twa species tolerate each ither oot o mutualism; tods provide badgers wi fuid scraps, while badgers maintain the shared burrow's cleanliness.[22]:15 Houiver, cases are kent o badgers drivin vixens frae thair dens an destroying thair litters wioot eatin them. Wolverines mey kill reid tods, eften while the latter are sleeping or near carrion. Tods in turn mey kill unattended young wolverines.[3]

Reid tods mey compete wi striped hyenas on lairge carcasses. Reid tods mey gie wey tae hyenas on unopened carcasses, as the latter's stranger jaws can easy tear open flesh that is too tough for tods. Tods mey harass hyenas, uisin thair smawer size an greater speed tae avyde the hyena's attacks. Whiles, tods seem tae deliberately torment hyenas even when thare is no fuid at stake. Some tods mey mistime thair attacks, an are killed.[8]:77–79 Fox remains are eften foond in hyena dens, an hyenas mey steal tods frae traps.[3]

In Eurasia, red tods mey be preyed upon bi leopards, caracals an Eurasian lynxes. The lynxes chase reid tods intae deep snaw, whaur thair langer legs an lairger paws gie them an advantage ower tods, especially when the depth o the snaw exceeds ane metre.[3] In the Velikoluki district in Roushie, red tods are absent or are seen anly occasionally whaur lynxes establish permanent territories.[3] Researchers consider lynxes tae represent considerably less danger tae reid tods than wolves dae.[3] North American felid predators o reid tods include cougars, Canadian lynxes an bobcats.[4] Occasionally, lairge raptors sic as Eurasian eagle owls will prey on young tods,[36] while golden eagles hae been kent tae kill adults.[37]

Range

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Reid tods are wide-rangin ainimals, whose range covers nearly 70 million km2 (27 million sq mi). Thay are distributed across the entire Northren Hemisphere frae the Arctic Circle tae North Africa, Central America, an Asia. Thay are absent in Iceland, the Arctic islands, some pairts o Siberia, an in extreme deserts.[1]

Reid tods are nae present in New Zealand an are clessed as a "prohibited new organism" unner the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, preventin them frae bein imported.[38]

Australie

[eedit | eedit soorce]In Australie, 2012 estimates indicate that thare are mair nor 7.2 million[39] reid tods wi a range extendin throughout maist o the continental mainland.[8]:14 The species became established in Australia throu successive introductions bi settlers in 1830s in the Breetish colonies o Van Diemen's Laund (as early as 1833) an the Port Phillip District o New South Wales (as early as 1845) for the purpose o the tradeetional Inglis sport o tod huntin. A permanent tod population wis nae established on the island o Tasmanie an it is widely held that thay war ootcompetit bi the Tasmanian deil.[40] On the mainland, houiver, the species wis successfu as an apex predator. It is generally less common in auries whaur the dingo is mair prevalent, houiver it haes, primarily throu its burraein behaviour, achieved niche differentiation wi baith the feral dog an the feral cat. As sic it haes acome ane o the continent's maist invasive species. The reid tod haes been implicated in the extinction an decline o several native Australian species, parteecularly thae o the faimily Potoroidae includin the desert rat-kangaroo.[41] The spread o reid tods across the soothren pairt o the continent haes coincided wi the spread o rabbits in Australia an corresponds wi declines in the distribution o several medium-sized grund-dwellin mammals, includin brush-tailed bettongs, burraein bettongs, rufous bettongs, bilbys, numbats, bridled nailtail wallabys an quokkas.[42] Most o thir species are nou leemitit tae auries (sic as islands) whaur reid tods are absent or rare. Local eradication programs exist, awtho eradication haes proven difficult due tae the dennin behaviour an nocturnal huntin, sae the focus is on management wi the introduction o state bounties.[43] Accordin tae the Tasmanian govrenment, reid tods war introduced tae the previously fox-free island o Tasmania in 1999 or 2000, posin a significant threat tae native wildlife includin the eastern bettong, an an eradication program conducted bi the Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries and Water haes been established.[44]

Sardinie

[eedit | eedit soorce]The oreegin o the Sardinian ichnusae subspecies is uncertaint, as it is absent frae Pleistocene deposits in thair current hqmeland. It is possible it oreeginatit durin the Neolithic follaein its introduction tae the island bi humans. It is likely then that Sardinian tod populations stem frae repeatit introductions o ainimals frae different localities in the Mediterranean. This latter theory mey expleen the subspecies' phenotypic diversity.[45]

Diseases and parasites

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Reid tods are the maist important rabies vector in Europe. In Lunnon, arthritis is nae uncommon in tods, bein parteecularly frequent in the spine.[5] Tods mey be infectit wi leptospirosis an tularemia, tho thay are nae overly susceptible tae the latter. Thay mey an aw faw ill frae listeriosis an spirochetosis, as well as actin as vectors in spreadin erysipelas, brucellosis an tick-borne encephalitis. A mysterious fatal disease near Lake Sartlan in the Novosibirsk Oblast wis noted amang local reid tods, but the cause wis undetermined. The possibility wis considered that it wis caused bi an acute form o encephalomyelitis, which wis first observed in captive bred siller tods. Individual cases o tods infected wi Yersinia pestis are kent.[3]

Reid tods are nae readily prone tae infestation wi flechs. Species lik Spilopsyllus cuniculi are probably anly caught frae the tod's prey species, while others lik Archaeopsylla erinacei are catcht whilst traivellin. Flechs that feed on reid tods include Pulex irritans, Ctenocephalides canis an Paraceras melis. Ticks sic as Ixodes ricinus an I. hexagonus are nae uncommon in tods, an are teepically foond on nouricin vixens an kits still in thair yirds. The louse Trichodectes vulpis specifically targets tods, but is foond infrequently. The mite Sarcoptes scabiei is the maist important cause o mange in reid tods. It causes extensive hair loss, stairtin frae the base o the tail an hindfeet, then the rump afore muivin on tae the rest o the body. In the feenal stages o the condeetion, tods can lose maist o thair fur, 50% o thair body wecht an mey gnaw at infected extremities. In the epizootic phase o the disease, it uisually takes tods fower month tae die efter infection. Ither endoparasites include Demodex folliculorum, Notoderes, Otodectes cynotis (which is frequently foond in the ear canal), Linguatula serrata (which infects the nasal passages) an ringworms.[3]

Up tae 60 helminth species are kent tae infect tods in fur farms, while 20 are kent in the wild. Several coccidian species o the genera Isospora an Eimeria are an aw kent tae infect them.[3] The maist common nematode species foond in tod guts are Toxocara canis an Uncinaria stenocephala, Capillaria aerophila[46] an Crenosoma vulpis, the latter twa infect thair lungs. Capillaria plica infect the tod's bledder. Trichinella spiralis rarely affects them. The maist common tapeworm species in tods are Taenia spiralis an T. pisiformis. Others include Echinococcus granulosus an E. multilocularis. Eleven trematode species infect reid tods,[5] includin Metorchis conjunctus.[47]

References

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ a b c Macdonald, D. W.; Reynolds, J. C. (2008). "'Vulpes vulpes'". IUCN Reid Leet o Threatened Species. Version 2008. Internaitional Union for Conservation o Naitur. Retrieved 20 September 2013. Cite has empty unkent parameter:

|last-author-amp=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - ↑ Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. p. 40.CS1 maint: unrecognised leid (link)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmammals-of-ussr - ↑ a b c Larivière, Serge; Pasitschniak-Arts, Maria (1996). Vulpes vulpes (PDF). American Society of Mammalogists. Archived frae the original (PDF) on 31 October 2005. Retrieved 9 Julie 2016. Unknown parameter

|dead-url=ignored (help) - ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmammals-of-the-brit-isles - ↑ a b c Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 129

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Macdonald, David (1987). Running with the Fox (in English). Unwin Hyman, London. ASIN B00H1HVF8G.CS1 maint: unrecognised leid (link)

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. 2. JHU Press. p. 636. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- ↑ Burnie D and Wilson DE (eds.), Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult (2005), ISBN 0789477645

- ↑ Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 130

- ↑ Wilkes, David (5 Mairch 2012). "'Largest fox killed in UK' shot on Aberdeenshire farm". BBC News Online.

- ↑ a b c d Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbachrach - ↑ Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 131

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmammals-of-na - ↑ Fawcett, John K.; Fawcett, Jeanne M.; Soulsbury, Carl D. (2012). "Seasonal and sex differences in urine marking rates of wild red foxes Vulpes vulpes". Journal of Ethology. 31 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1007/s10164-012-0348-7.

- ↑ Walters, Martin; Bang, Preben; Dahlstrøm, Preben (2001). Animal tracks and signs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 0-19-850796-8.

- ↑ Henry, J. David (1977). "The use of urine marking in the scavenging behavior of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes)". Behaviour. 61 (1/2): 82–106. doi:10.1163/156853977X00496. JSTOR 4533812.

- ↑ Andersen, K. F.; Vulpius, T. (1999). "Urinary volatile constituents of the lion, Panthera leo". Chemical Senses. 24 (2): 179–189. doi:10.1093/chemse/24.2.179. PMID 10321819.

- ↑ Elbroch, Lawrence Mark; Kresky, Michael Raymond; Evans, Jonah Wy (2012). Field Guide to Animal Tracks and Scat of California. University of California Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-520-25378-0.

- ↑ Iossa, Graziella; et al. (2008). "Body mass, territory size, and life-history tactics in a socially monogamous canid, the red fox Vulpes vulpes". Journal of Mammalogy. 89 (6): 1481–1490. doi:10.1644/07-mamm-a-405.1. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last2=(help) - ↑ a b c d Dale, Thomas Francis (1906). The fox. London, New York, Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 8 Julie 2016.

- ↑ a b Hunter, L. (2011). Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-691-15227-1.

- ↑ Holland, Jennifer S. (Julie 2011). "40 winks?". National Geographic. 220 (1).

- ↑ Asa C. S., Mech D. (1995). "A review of the sensory organs in wolves and their importance to life history," in Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World eds. Carbyn L. D., Fritts S. H., Seip D. R., editors. (Edmonton: Canadian Circumpolar Institute; ) 287–291

- ↑ osterholm H. (1964). The significance of distance reception in the feeding behaviour of fox (Vulpes vulpes L.). Acta Zool. Fenn. 106 1–31

- ↑ Wells M. C. (1978). Coyote senses in predation – environmental influences on their relative use. Behav. Processes 3 149–158 10.1016/0376-6357(78)90041-4

- ↑ Wells M. C., Lehner P. N. (1978). Relative importance of distance senses in Coyote predatory behavior. Anim. Behav. 26 251–258 10.1016/0003-3472(78)90025-8

- ↑ Yong, Ed (11 Januar 2011). "Foxes use the Earth's magnetic field as a targeting system - Not Exactly Rocket Science". Discover Magazine. Archived frae the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ↑ Jaroslav Červený; Sabine Begall; Petr Koubek; Petra Nováková; Hynek Burda (12 Januar 2011). "Directional preference may enhance hunting accuracy in foraging foxes". Biol. Lett. 7: 355–357. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.1145. PMC 3097881.

- ↑ Heptner & Naumov 1998, pp. 453–454

- ↑ Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi (2003). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-226-51696-2.

- ↑ Sargeant, Alan B; Allen, Stephen H. (1989). "Observed interactions between coyotes and red foxes". Journal of Mammalogy. 70 (3): 631–633. doi:10.2307/1381437. JSTOR 1381437. Archived frae the original on 14 November 2007. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ Scheinin, Shani; Yom-Tov, Yoram; Motro, Uzi; Geffen, Eli (2006). "Behavioural responses of red foxes to an increase in the presence of golden jackals: A field experiment" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 71 (3): 577–584. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.05.022.

- ↑ Sillero-Zubiri, Hoffman & MacDonald 2004, p. 134

- ↑ "Eurasian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) - Information, Pictures, Sounds". The Owl Pages. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Watson, Jeff (2010). The Golden Eagle (2nd ed.). A&C Black. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4081-1420-9.

- ↑ "Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 2003 – Schedule 2 Prohibited new organisms". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 26 Januar 2012.

- ↑ "Impacts of Feral Animals". Game Council of New South Wales. Archived frae the original on 18 Apryle 2012. Retrieved 29 Mey 2012. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) "Archived copy". Archived frae the original on 18 Apryle 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Bostanci, A. (2005). "Wildlife Biology: A Devil of a Disease". Science. 307 (5712): 1035. doi:10.1126/science.307.5712.1035. PMID 15718445.

- ↑ Short, J. (1998). "The extinction of rat-kangaroos (Marsupialia:Potoroidae) in New South Wales, Australia". Biological Conservation. 86 (3): 365–377. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00026-3.

- ↑ Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) (PDF) (Report). NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. 2001. ISBN 0731364244.

- ↑ Millen, Tracey (October–November 2006). "Call for more dingoes to restore native species" (PDF). ECOS. 133. (Refers to the book Australia's Mammal Extinctions: a 50,000 year history. Christopher N. Johnson. ISBN 978-0-521-68660-0.)

- ↑ "Latest Physical Evidence of Foxes in Tasmania". Department of Primary Industries and Water, Tasmania website. 18 Julie 2013. Archived frae the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Spagnesi & De Marina Marinis 2002, p. 222

- ↑ Lalošević, V.; Lalošević, D.; Čapo, I.; Simin, V.; Galfi, A.; Traversa, D. (2013). "High infection rate of zoonotic Eucoleus aerophilus infection in foxes from Serbia". Parasite. 20 (3): 3. doi:10.1051/parasite/2012003. PMC 3718516. PMID 23340229.

- ↑ Smith, H. J. (1978). "Parasites of red foxes in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 14 (3): 366–370. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-14.3.366. PMID 691132.