Brexit

This airticle needs tae be updatit. |

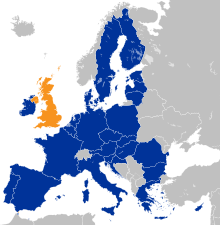

Brexit (fae "British exit") wis the widrawal o the Unitit Kinrick (UK) frae the European Union (EU) follaein a 2016 referendum held on 23 Juin 2016 in that 51.9 per cent o the UK supportit leavin the EU. Majorities in Ingland an Wales baith supported leave (Leave 53.4% in Ingland, 52.5% in Wales); howsomever, in Scotlan an Northren Irelan, maist fowk favoured memmership o the EU (Remain 62.0% in Scotland; 55.8% in Norlin Ireland).[1]

Follaein thae vote, the Govrenment invoked Airticle 50 o the Treaty on European Union, stairtin a twa-year process that wis due tae conclude wi the UK's exit on 29 Mairch 2019.[2] Efter an extension, the UK left the EU at 11 p.m. GMT on 31 January 2020 an entered intae a period o transition, durin which the UK and EU are negotiatin their future relationship.[3] Fae the noo, the UK is pairtie tae EU law an is a pairt o the customs union and single market durin the transition, but isnae langer pairt o EU political bodies or institutions.[4][5]

Euroscepticism (anti-EU feelin) is associatit wi the poleetical richt the day, but widrawal frae the EU haes been advocatit bi baith left-weeng an richt-weeng Eurosceptics. Pro-Europeanists, that span the poleetical spectrum an aw, hae advocatit conteena'd membership. The UK jynt the European Communities (EC) in 1973 unner the Conservative govrenment o Edward Heath, wi conteena'd membership endorsed bi a referendum in 1975. In the 1970s an 1980s, widrawal frae the EC wis advocatit mainly bi the poleetical left, wi the Labour Pairty's 1983 election manifesto advocatin full widrawal. Frae the 1990s, opposeetion tae faur European integration cam mainly frae the richt, an diveesions within the Conservative Pairty led tae rebellion ower the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. The growthe o the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in the early 2010s an the influence o the cross-pairty People's Pledge campaign hae been descrived as influential in bringin aboot a referendum. The Tory Prime Meenister, David Cameron, plichtit in the campaign for the 2015 UK General Election tae haud a new referendum—a plicht that he fulfilled in 2016 follaein pressur frae the Eurosceptic weeng o his pairty. Cameron, that had campaigned tae remain, resigned efter the result an wis succeedit bi Theresa May, his umwhile Hame Secretar. She cried a snap general election less nor a year later, but lost her oweraw majority. Her minority govrenment wis supportit in key votes bi the Democratic Unionist Pairty till her resignation.

On 29 Mairch 2017, the Govrenment o the Unitit Kinrick invoked Airticle 50 o the Treaty on European Union. May annoonced the govrenment's intention nae tae seek permanent membership o the European single mercat or the EU customs union efter leavin the EU an promised tae repeal the European Communities Act o 1972 an incorporate existin European Union law intae UK domestic law. Negotiations wi the EU offeecially stairtit in Juin 2017. In November 2018, the Draft Withdrawal Agreement, negotiatit atween the UK Govrenment an the EU, wis published. The Hoose o Commons votit against the greement bi a mairgin o 432 tae 202 (the lairgest pairlamentar defeat in history for a sittin UK govrenment) on 15 Januar 2019, an again on 12 Mairch wi a mairgin o 391 tae 242 against the greement. On 14 Mairch 2019, the Hoose o Commons votit for the Prime Meenister, Theresa May, tae ask the EU for sic an extension o the period alloued for the negotiation.[6] Members frae athort the Hoose o Commons rejectit the greement wi the leadership o the Labour Party statin in public debates in the Hoose o Commons that ony deal maun maintain a customs union an single mercat, an wi a lairge percentage o its members rejectin the Erse backstap as it is currently draftit in the EU widrawal greement. Opponents o the EU Withdrawal Agreement citit concerns that the greement as draftit coud plunge Northren Ireland intae a conflict an spark a return o the Truibils as a result o Brexit.

Having failed to get her greement approved, May resigned as Prime Minister in Julie and wis succeeded bi the Eurosceptic Boris Johnson. He socht tae replace pairts o the greement and voued tae leave the EU bi the new deadline. On 17 October 2019, the British govrenment and the EU agreed on a revised widrawal greeance, wi new arrangements for Northren Ireland.[7][8] Pairlament approued the greement for mair scrutiny, but rejected passing it intae law afore the 31 October deidline, and forced the govrenment (thru the "Benn Act") to ask for a third Brexit delay. An early general election wis then held on 12 December. The Conservatives won a majority, wi Johnson sayin the UK would leave the EU in early 2020.[9] The withdrawal greeance wis ratified bi the UK on 23 January an bi the EU on 30 January; it cam intae force on 31 January 2020.[10][11][12]

The braid consensus amang economists is that Brexit will likely reduce the UK's real per capita income in the medium term an lang term, an that the Brexit referendum itsel damaged the economy.[a] Studies on effects syne the referendum shaw a reduction in GDP, tred an investment, as weel as hoosehaud losses frae increased inflation. Brexit is likely tae reduce immigration frae European Economic Aurie (EEA) kintras tae the UK, an poses challenges for UK heicher eddication an academic resairch. As o Mairch 2019[update], the size o the "divorce bill"—the UK's inheritance o existin EU tred greements—an relations wi Ireland an ither EU member states remeens uncertaint. The precise impact on the UK depends on whither the process will be a "haurd" or "saft" Brexit. Brexit offeecially teuk place on 31 Januar 2020.

Notes

[eedit | eedit soorce]References

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/politics/eu_referendum/results

- ↑ Tusk, Donald (10 Apryle 2019). "EU27/UK have agreed a flexible extension until 31 October. This means additional six months for the UK to find the best possible solution". @eucopresident (in Inglis). Twitter. Retrieved 11 Apryle 2019.

- ↑ Asa Bennett (27 Januar 2020). "How will the Brexit transition period work?". Telegraph. Archived frae the original on 28 Januar 2020. Retrieved 28 Januar 2020.

- ↑ Tom Edgington (31 Januar 2020). "Brexit: What is the transition period?". BBC News. Archived frae the original on 31 Januar 2020. Retrieved 1 Februar 2020.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers on the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union on 31 January 2020". European Commission. 24 Januar 2020. Archived frae the original on 1 Februar 2020. Retrieved 1 Februar 2020.

- ↑ "House of Commons votes to seek Article 50 extension". 14 Mairch 2019. Retrieved 11 Mey 2020.

- ↑ "Revised Withdrawal Agreement" (PDF). European Commission. 17 October 2019. Archived (PDF) frae the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ "New Brexit deal agreed, says Boris Johnson". BBC News. 17 October 2019. Archived frae the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ Landler, Mark; Castle, Stephen (12 December 2019). "Conservatives Win Commanding Majority in U.K. Vote: 'Brexit Will Happen'". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived frae the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019 – via MSN.

- ↑ Boffey, Daniel; Proctor, Kate (24 Januar 2020). "Boris Johnson signs Brexit withdrawal agreement". The Guardian. Archived frae the original on 24 Januar 2020. Retrieved 24 Januar 2020.

- ↑ Sparrow, Andrew (30 Januar 2020). "Brexit: MEPs approve withdrawal agreement after emotional debate and claims UK will return – live news". The Guardian. Archived frae the original on 29 Januar 2020. Retrieved 30 Januar 2020.

- ↑ "Brexit: UK leaves the European Union". BBC News. 1 Februar 2020. Archived frae the original on 14 Mairch 2020. Retrieved 11 Apryle 2020.

- ↑ Goodman, Peter S. (20 Mey 2016). "'Brexit,' a Feel-Good Vote That Could Sink Britain's Economy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

finding economists who say they believe that a Brexit will spur the British economy is like looking for a doctor who thinks forswearing vegetables is the key to a long life

- ↑ Sampson, Thomas (2017). "Brexit: The Economics of International Disintegration". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 31 (4): 163–184. doi:10.1257/jep.31.4.163. ISSN 0895-3309.

The results I summarize in this section focus on long-run effects and have a forecast horizon of 10 or more years after Brexit occurs. Less is known about the likely dynamics of the transition process or the extent to which economic uncertainty and anticipation effects will impact the economies of the United Kingdom or the European Union in advance of Brexit.

- ↑ Baldwin, Richard (31 Julie 2016). "Brexit Beckons: Thinking ahead by leading economists". VoxEU.org. Archived frae the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

On 23 June 2016, 52% of British voters decided that being the first country ever to leave the EU was a price worth paying for 'taking back control', despite advice from economists clearly showing that Brexit would make the UK 'permanently poorer' (HM Treasury 2016). The extent of agreement among economists on the costs of Brexit was extraordinary: forecast after forecast supported similar conclusions (which have so far proved accurate in the aftermath of the Brexit vote).

- ↑ "Brexit survey". igmchicago.org. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "Brexit survey II". igmchicago.org. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ Sodha, Sonia; Helm, Toby; Inman, Phillip (28 Mey 2016). "Economists overwhelmingly reject Brexit in boost for Cameron". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "Most economists still pessimistic about effects of Brexit". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Unlike the short-term effects of Brexit, which have been better than most had predicted, most economists say the ultimate impact of leaving the EU still appears likely to be more negative than positive. But the one thing almost all agree upon is that no one will know how big the effects are for some time.

- ↑ Wren-Lewis, Simon. "Why is the academic consensus on the cost of Brexit being ignored?". The Conversation (in Inglis). Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "Brexit to Hit Jobs, Wealth and Output for Years to Come, Economists Say". Bloomberg L.P. 22 Februar 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

The U.K. economy may be paying for Brexit for a long time to come... It won't mean Armageddon, but the broad consensus among economists—whose predictions about the initial fallout were largely too pessimistic—is for a prolonged effect that will ultimately diminish output, jobs and wealth to some degree.

- ↑ Johnson, Paul; Mitchell, Ian (1 Mairch 2017). "The Brexit vote, economics, and economic policy". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 33 (suppl_1): S12–S21. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grx017. ISSN 0266-903X.

- ↑ "Most economists say Brexit will hurt the economy – but one disagrees". The Economist (in Inglis). Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ↑ "This is the real reason the UK's economic forecasts look so bad". The Independent. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

One thing economists do generally agree on is that leaving the European Union and putting new trade barriers between Britain and our largest and closest trading partners is extremely unlikely to boost UK productivity growth—and is far more likely to slow it

- Articles with redirect hatnotes needing review

- Wikipaedia airticles in need o updatin

- Aw Wikipaedia airticles in need o updatin

- Brexit

- 2010s in politics

- 2016 in Breetish politics

- Consequences o the Unitit Kinrick European Union membership referendum, 2016

- Inglis wirds an phrases

- Euroscepticism in the Unitit Kinrick

- Unitit Kinrick an the European Union

- Widrawal frae the European Union

- Wirds coined in the 2010s