Horse

The "Scots" that wis uised in this airticle wis written bi a body that haesna a guid grip on the leid. Please mak this airticle mair better gin ye can. (Dizember 2020) |

| Horse | |

|---|---|

| |

Domesticatit

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kinrick: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Cless: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Faimily: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | E. ferus |

| Subspecies: | E. f. caballus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Equus ferus caballus | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

at least 48 published | |

The horse (Equus ferus caballus)[2][3] is ane o twa extant subspecies o Equus ferus. It is an odd-taed ungulate mammal belangin tae the taxonomic faimily Equidae. Accordin tae scienteefic consensus, the horse hae evolvit ower the past 45 tae 55 million years fae a wee multi-taed craitur, Eohippus, intae the muckle single-taed ainimal o the day. Humans begane tae domesticate the horse aroond 4000 BC, an thair domestication is believed tae hae been widespread bi 3000 BC. Horse in the subspecies caballus are domesticatit, awtho some domesticatit populations leeve in the wild as feral horse. Thir feral populations are no true wild horse, as this term is uised tae descrive horse that hae niver been domesticatit, sic as the endangered Przewalski's horse, a separate subspecies, an the anerly remeenin true wild horse. Thare is an extensive, specializit vocabulary uised tae descrive equine-relatit concepts, cowerin iverything fae anatomy tae life stages, size, colours, merkins, breeds, locomotion, an behaviour.

Horse anatomy enables them tae mak uise o speed tae escape predators an thay hae a well-developit sense o balance an a strang fecht-or-flicht response. Relatit tae this need tae flee frae predators in the wild is an unuisual trait: horse are able tae sleep baith staundin up an leein doun. Female horse, cried meirs, cairy thair young for approximately 11 months, an a young horse, cried a foal, can staund an run shortly follaein birth. Maist domesticatit horse begin trainin unner saidle or in harnish atween the ages o twa an fower. Thay reach full adult development bi age five, an hae an average lifespan o atween 25 an 30 years.

Horse breeds are lowsely dividit intae three categories based on general temperament: speeritit "het bluids" wi speed an endurement; "cauld bluids", sic as draucht horse an some pownies, suitable for slaw, hivy wirk; an "wairmbluids", developed frae crosses atween het bluids an cauld bluids, eften focusin on creautin breeds for speceefic ridin purposes, pairteecularly in Europe. Thare are mair nor 300 breeds o horse in the warld the day, developed for mony different uises.

Horse an humans interact in a wide variety o sport competeetions an non-competitive recreautional pursuits, as well as in wirkin activities sic as polis wirk, agricultur, enterteenment, an therapy. Horse war historically uised in warfare, frae which a wide variety o ridin an drivin techniques developed, uisin mony different styles o equipment an methods o control. Mony products are derived frae horse, includin meat, milk, hide, hair, bane, an pharmaceuticals extractit frae the urine o pregnant mares. Humans provide domesticatit horse wi fuid, watter an shelter, as well as attention frae specialists sic as veterinarians an ferriers.

Biology

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Specific terms an specialised leid are uised tae descrive equine anatomy, different life stages, colours an breeds.

Lifespan an life stages

[eedit | eedit soorce]Dependin on breed, management an environment, the modren domestic horse haws a life expectancy o 25 tae 30 years.[6] Uncommonly, a few ainimals live intae thair 40s an, occasionally, ayont.[7] The auldest verifiable record wis "Old Billy", a 19t-century horse that lived tae the age o 62.[6] In modren times, Sugar Puff, wha haed been leetit in Guinness World Records as the warld's auldest leevin pownie, dee'd in 2007 at age 56.[8]

Regairdless o a horse or pownie's actual birth date, for maist competeetion purposes a year is addit tae its age ilk Januar 1 o ilk year in the Northren Hemisphere[6][9] an ilk August 1 in the Soothren Hemisphere.[10] The exception is in endurement ridin, whaur the meenimum age tae compete is based on the ainimal's actual calendar age.[11]

The follaein terminology is uised tae descrive horse o various ages:

- Cowt: A male horse unner the age o fower.[12] A common terminology error is tae caw ony young horse a "cowt", whan the term actually anerly refers tae young male horse.[13]

- Filly: A female horse unner the age o fower.[14]

- Foal: A horse o aither sex less nor ane year auld. A nursin foal is while cried a soukie an a foal that haes been weaned is cried a weanlin.[14] Maist domesticatit foals are weaned at five tae seeven month o age, awtho foals can be weaned at fower month wi na adverse pheesical effects.[15]

- Libbin: A libbed male horse o ony age.[14]

- Meir: A female horse fower year auld an aulder.[16]

- Couser: A non-libbit male horse fower year auld an aulder.[17] The term "horse" is whiles uised colloquially tae refer specifically tae a stallion.[18]

- Yearauld: A horse o aither sex that is atween ane an twa year auld.[19]

In horse racin, thir defineetions mey differ: For example, in the Breetish Isles, Thoraebred horse racin defines cowts an fillies as less nor five year auld.[20] Houiver, Australie Thoraebred racin defines cowts an fillies as less nor fower year auld.[21]

Size an meisurment

[eedit | eedit soorce]The hicht o horse is uisually meisurt at the heichest pynt o the withers, whaur the neck meets the back.[22] This pynt is uised acause it is a stable pynt o the anatomy, unlik the heid or neck, that muive up an doun in relation tae the bouk o the horse.

The size o horse varies bi breed, but is influenced bi nutreetion an aw. Licht ridin horse uisually range in hicht frae 14 to 16 haunds (56 to 64 inches, 142 to 163 cm) an can wecht frae 380 tae 550 kilogram (840 tae 1,210 lb).[23] Lairger ridin horse uisually stairt at aboot 15.2 haunds (62 inches, 157 cm) an eften are as taw as 17 haunds (68 inches, 173 cm), wechtin frae 500 tae 600 kilogram (1,100 tae 1,320 lb).[24] Hivy or draucht horse are uisually at least 16 haunds (64 inches, 163 cm) heich an can be as taw as 18 haunds (72 inches, 183 cm) heich. Thay can wecht frae aboot 700 tae 1,000 kilogram (1,540 tae 2,200 lb).[25]

The lairgest horse in recordit history wis probably a Shire horse named Mammoth, wha wis born in 1848. He stuid 21.2 1⁄4 haunds (86.25 inches, 219 cm) heich an his peak wecht wis estimatit at 1,524 kilogram (3,360 lb).[26] The current record hauder for the warld's smawest horse is Thumbelina, a fully matur miniature horse affectit bi dwarfism. She is 17 in (43 cm) taw an wechts 57 lb (26 kg).[27]

Pownies

[eedit | eedit soorce]Pownies are taxonomically the same ainimals as horse. The distinction atween a horse an pownie is commonly drawn on the basis o hicht, especially for competeetion purposes. Houiver, hicht alone is nae dispositive; the difference atween horse an pownies mey include aspects o phenoteep an aw, includin conformation an temperament.

The tradeetional staundart for hicht o a horse or a pownie at maturity is 14.2 haunds (58 inches, 147 cm). An ainimal 14.2 h or ower is uisually conseedert tae be a horse an ane less nor 14.2 h a pownie,[28] but thare are mony exceptions tae the tradeetional staundart. In Australie, pownies are conseedert tae be thae unner 14 haunds (56 inches, 142 cm).[29] For competeetion in the Wastren diveesion o the United States Equestrian Federation, the cutaff is 14.1 haunds (57 inches, 145 cm).[30] The Internaitional Federation for Equestrian Sport, the warld govrenin bouk for horse sport, uises metric meisurments an defines a pownie as bein ony horse measurin less nor 148 centimetre (58.27 in) at the withers withoot shaes, that is juist ower 14.2 h, an 149 centimetre (58.66 in), or juist ower 14.2½ h, wi shaes.[31]

Hicht is nae the sole criterion for distinguishin horse frae pownies. Breed registries for horse that teepically produce individuals baith unner an ower 14.2 h conseeder aw ainimals o that breed tae be horse regairdless o thair hicht.[32] Conversely, some pownie breeds mey hae featurs in common wi horse, an individual ainimals mey occasionally matur at ower 14.2 h, but are still conseedert tae be pownies.[33]

Pownies eften exhibit thicker manes, tails, an oweraw coat. Thay forby hae proportionally shorter legs, wider baurels, hivier bane, shorter an thicker necks, an short heids wi braid foreheids. Thay mey hae caumer temperaments nor horse an a heich level o intelligence that mey or mey nae be uised tae cooperate wi human haundlers an aw.[28] Smaw size, bi itsel, is nae an exclusive determinant. For ensaumple, the Shetland pownie that averages 10 haunds (40 inches, 102 cm), is conseedert a pownie.[28] Conversely, breeds sic as the Falabella an ither miniatur horse, that can be na tawer nor 30 inches (76 cm), are clessifee'd bi thair registries as verra smaw horse, nae pownies.[34]

Genetics

[eedit | eedit soorce]Horse hae 64 chromosomes.[35] The horse genome wis sequenced in 2007. It conteens 2.7 billion DNA base pairs,[36] that is lairger nor the dug genome, but smawer nor the human genome or the bovine genome.[37] The cairt is available tae resairchers.[38]

Colours an merkins

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Horse exhibit a diverse array o coat colours an distinctive merkins, descrived bi a specialised vocabulary. Eften, a horse is clessifee'd first bi its coat colour, afore breed or sex.[39] Horse o the same colour mey be distinguished frae ane anither bi white merkins,[40] that, alang wi various spottin patterns, are inheritit separately frae coat colour.[41]

Mony genes that creaut horse coat colours an patterns hae been identifee'd. Current genetic tests can identify at least 13 different alleles influencin coat colour,[42] an resairch conteenas tae discover new genes airtit tae speceefic traits. The basic coat colours o chestane an black are determined bi the gene controlled bi the Melanocortin 1 receptor,[43] forby kent as the "extension gene" or "reid factor",[42] as its recessive form is "reid" (chestane) an its dominant form is black.[44] Addeetional genes control suppression o black colour tae pynt colouration that results in a bay, spottin patterns sic as pinto or leopard, dilution genes sic as palomino or dun, as well as graying, an aw the ither factors that creaut the mony possible coat colours foond in horse.[42]

Horse that hae a white coat colour are eften mislabeled; a horse that looks "white" is uisually a middle-aged or aulder gray. Grays are born a daurker shade, get lichter as thay age, but uisually keep black skin aneath thair white hair coat (wi the exception o pink skin unner white merkins). The anerly horse properly cried white are born wi a predominantly white hair coat an pink skin, a fairly rare occurrence.[44] Different an unrelatit genetic factors can produce white coat colours in horse, includin several different alleles o dominant white an the sabino-1 gene.[45] Houever, thare are na "albino" horse, defined as haein baith pink skin an reid een.[46]

Reproduction an development

[eedit | eedit soorce]Gestation lasts approximately 340 days, wi an average range 320–370 days,[47] an uisually results in ane foal; twins are rare.[48] Horse are a precocial species, an foals are capable o staundin an runnin within a short time follaein birth.[49] Foals are uisually born in the ware. The oestrus cycle o a mare occurs aboot ivery 19–22 days an occurs frae early ware intae hairst. Maist mares enter an anoestrus period in the winter an sicweys dae nae cycle in this period.[50] Foals are generally weaned frae thair mithers atween fower an sax month o age.[51]

Horse, pairticularly cowts, whiles are pheesically capable o reproduction at aboot 18 months, but domesticatit horse are rarely alloued tae breed afore the age o three, especially females.[52] Horse fower year auld are conseedert matur, awtho the skelet normally conteenas tae develop till the age o sax; maturation depends on the horse's size, breed, sex, an quality o care an aw. Lairger horse hae lairger banes; tharefore, nae anerly dae the banes tak langer tae form bane tishie, but the epiphyseal plates are lairger an tak langer tae convert frae cartilage tae bane. Thir plates convert efter the ither pairts o the banes, an are crucial tae development.[53]

Dependin on maturity, breed, an wirk expectit, horse are uisually put unner saidle an trained tae be ridden atween the ages o twa an fower.[54] Awtho Thoraebred race horse are put on the track as young as the age o twa in some kintras,[55] horse speceefically bred for sports sic as dressage are generally nae pit unner saidle till thay are three or fower year auld, acause thair banes an muscles are nae solitly developed.[56] For endurement ridin competeetion, horse are nae deemed matur enough tae compete till thay are a full 60 calendar months (five years) auld.[11]

Anatomy

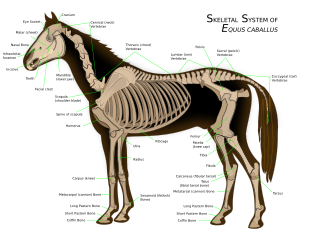

[eedit | eedit soorce]Skeletal seestem

[eedit | eedit soorce]

The horse skelet averages 205 banes.[57] A signeeficant difference atween the horse skelet an that o a human is the lack o a hausebane—the horse's forelimms are attached tae the spinal column bi a pouerfu set o muscles, tenons, an ligaments that attach the shoulder blade tae the torso. The horse's legs an huifs are unique structurs an aw. Thair leg banes are proportioned differently frae thae o a human. For ensaumple, the bouk pairt that is cried a horse's "knee" is actually made up o the carpal banes that correspond tae the human wrist. Similarly, the hock contens banes equivalent tae thae in the human ankle an heel. The lawer leg banes o a horse correspond tae the banes o the human haund or fit, an the fetlock (incorrectly cried the "anklet") is actually the proximal sesamoid banes atween the cannon banes (a single equivalent tae the human metacarpal or metatarsal banes) an the proximal phalanges, locatit whaur ane finds the "knuckles" o a human. A horse haes na muscles in its legs ablo the knees an hocks, anerly skin, hair, bane, tenons, ligaments, cartilage, an the assortit specialised tishies that mak up the huif.[58]

Huifs

[eedit | eedit soorce]The creetical importance o the feet an legs is summed up bi the tradeetional adage, "na fit, na horse".[59] The horse huif begins wi the distal phalanges, the equivalent o the human fingertip or tip o the tae, surroondit bi cartilage an ither specialised, bluid-rich saft tishies sic as the laminae. The exterior huif waw an horn o the sole is made o keratin, the same material as a human fingernail.[60] The end result is that a horse, wechtin on average 500 kilogram (1,100 lb),[61] traivels on the same banes as wad a human on tiptoe.[62] For the pertection o the huif unner certain condeetions, some horse hae horseshaes placed on thair feet bi a perfaisional ferrier. The huif conteenually growes, an in maist domesticatit horse needs tae be trimmed (an horseshaes reset, if uised) ivery five tae aicht weeks,[63] tho the huifs o horse in the wild wear doun an regroweat a rate suitable for thair terrain.

Teeth

[eedit | eedit soorce]Horse are adaptit tae grazin. In an adult horse, thare are 12 incisors at the front o the mooth, adaptit tae bitin aff the gress or ither vegetation. Thare are 24 teeth adaptit for chewin, the premolars an molars, at the back o the mooth. Cousers an libbins hae fower addeetional teeth juist ahint the incisors, a teep o canine teeth cried "tushes". Some horse, baith male an female, will develop ane tae fower verra smaw vestigial teeth in front o the molars, kent as "wouf" teeth, that are generally remuived acause thay can interfere wi the bit. Thare is an emptie interdental space atween the incisors an the molars whaur the bit rests directly on the gums, or "bars" o the horse's mooth whan the horse is bridled.[64]

An estimate o a horse's age can be made frae leukin at its teeth. The teeth conteeina tae erupt ootthrou life an are worn doun bi grazing. Tharefore, the incisors shaw cheenges as the horse ages; thay develop a distinct wear pattern, cheeanges in tuith shape, an cheenges in the angle at that the chewin surfaces meet. This allous an estimate o a horse's age, awtho diet an veterinary care can affect the rate o tuith wear an aw.[6]

Digeestion

[eedit | eedit soorce]Horse are yerbivores wi a digeestive seestem adaptit tae a forage diet o gresses an ither plant material, consumed steadily ootthrou the day. Tharefore, compared tae humans, thay hae a relatively smaw painch but verra lang thairms tae facilitate a steidy flow o nutrients. A 450-kilogram (990 lb) horse will eat 7 tae 11 kilogram (15 tae 24 lb) o fuid per day an, unner normal uise, drink 38 tae 45 litre (8.4 tae 9.9 imp gal; 10 tae 12 US gal) o watter. Horse are nae ruminants, thay hae anerly oane painch, lik humans, but unlik humans, thay can utilize cellulose, a major component o gress. Horse are hindgut fermenters. Cellulose fermentation bi symbiotic bacteria occurs in the cecum, or "watter gut", that fuid gaes throu afore reachin the lairge intestine. Horse canna vomit, sae digeestion problems can quickly cause colic, a leadin cause o daith.[65]

Senses

[eedit | eedit soorce]

The horse' senses are based on thair status as prey ainimals, whaur thay maun be awaur o thair surroondins at aw times.[66] Thay hae the lairgest een o ony laund mammal,[67] an are lateral-eed, meanin that thair een are poseetioned on the sides o thair heids.[68] This means that horse hae a range o veesion o mair nor 350°, wi approximately 65° o this bein binocular veesion an the remainin 285° monocular veesion.[67] Horse hae excellent day an nicht veesion, but thay hae twa-colour, or dichromatic veesion; thair color veesion is somewhit lik reid-green colour blindness in humans, whaur certain colours, especially reid an relatit colours, appear as a shade o green.[69]

Thair sense o smell, while muckle better nor that o humans, is nae quite as guid as that o a dug. It is believed tae play a key role in the social interactions o horse as well as detectin ither key scents in the environment. Horse hae twa olfactory centres. The first seestem is in the nostrils an nasal cavity, that analyze a wide range o odours. The seicont, locatit unner the nasal cavity, are the Vomeronasal organs, cried the Jacobson's organs an aw. Thir hae a separate nerve pathway tae harn an appear tae primarily analyze pheromones.[70]

A horse's hearin is guid,[66] an the pinna o ilk lug can rotate up tae 180°, giein the potential for 360° hearin withoot haein tae muive the heid.[71] Noise impacts the behaviour o horse an certain kinds o noise mey contreibute tae stress: A 2013 study in the UK indicated that stabled horse war caumest in a quiet settin, or if listenin tae country or clessical muisic, but displayed signs o nervishness whan listenin tae jazz or rock muiic. This study recommended keepin muisic unner a vollum o 21 decibels an aw.[72] An Australie study foond that stabled racehorse listenin tae talk radio haed a heicher rate o gastric ulcers nor horse listenin tae muisic, an racehorse stabled whaur a radio wis played haed a heicher oweraw rate o ulceration nor horse stabled whaur thare wis na radio playin.[73]

Horse hae a great sense o balance, due pairtly tae thair abeelity tae feel thair fittin an pairtly tae heichly developed proprioception—the unconscious sense o whaurethe bouk an limms are at aw times.[74] A horse's sense o titch is well developed. The maist sensitive auries are aroond the een, lugs, an neb.[75] Horse are able tae sense contact as subtle as an insect laundin onywhaur on the bouk.[76]

Horse hae an advanced sense o taste, that allous them tae sort throu fother an chuise whit thay wad maist lik tae eat,[77] an thair prehensile lips can easily sort even smaw grains. Horse generally will nae eat pushionous plants, houiver, thare are exceptions; horse will occasionally eat toxic amoonts o pushionous plants even whan thare is adequate halthy fuid.[78]

Muivement

[eedit | eedit soorce]

Aw horse muive naiturally wi fower basic gangs: the fower-beat walk, that averages 6.4 kilometres per hour (4.0 mph); the twa-beat trot or jog at 13 tae 19 kilometres per hour (8.1 tae 11.8 mph) (fester for harness racin horse); the canter or lope, a three-beat gang that is 19 tae 24 kilometres per hour (12 tae 15 mph); an the gallop.[79] The gallop averages 40 tae 48 kilometres per hour (25 tae 30 mph),[80] but the warld record for a horse gallopin ower a short, sprint distance is 70.76 kilometres per hour (43.97 mph).[81] Besides thir basic gangs, some horse perform a twa-beat pace, insteid o the trot.[82] Thare are several foweur-beat "amblin" gangs that are approximately the speed o a trot or pace an aw, tho smuither tae ride. Thir include the lateral rack, runnin walk, an tölt as well as the diagonal tod trot.[83] Amblin gangs are eften genetic in some breeds, kent collectively as gangit horse.[84] Eften, gangit horse replace the trot wi ane o the amblin gangs.[85]

Behaviour

[eedit | eedit soorce]Horse are prey ainimals wi a strang fecht-or-flicht response. Theair first reaction tae threat is tae stairtle an uisually flee, awtho thay will staund thair grund an defend themsels whan flicht is impossible or if thair young are threatened.[86] Thay tend tae be curious an aw; whan stairtled, thay will eften hesitate an instant tae ascertain the cause o thair fricht, an mey nae ayeweys flee frae something that thay perceive as non-threatenin. Maist licht horse ridin breeds war developed for speed, agility, alertness an endurement; naitural qualities that extend frae thair wild auncestors. Houiver, throu selective breedin, some breeds o horse are quite docile, pairticularly certain draucht horse.[87]

Horse are herd ainimals, wi a clear hierarchy o rank, led bi a dominant individual, uisually a meir. Thay are social craiturs that are able tae form companionship attachments tae thair awn species an tae ither ainimals, includin humans. Thay communicate in various weys, includin vocalisations sic as nickerin or whinnyin, mutual gruimin, an bouk leid. Mony horse will acome difficult tae manage if thay are isolatit, but wi trainin, horse can learn tae accept a human as a companion, an sicweys be comfortable awey frae ither horse.[88] Houiver, whan confined wi insufficient companionship, exercise, or stimulation, individuals mey develop stable vices, an assortment o bad habits, maistly stereotypies o psychological oreegin, that include wid chewin, waw kickin, "weavin" (rockin back an forth), an ither problems.[89]

Intelligence an learnin

[eedit | eedit soorce]Studies hae indicatit that horse perform a nummer o cognitive tasks on a daily basis, meetin mental challenges that include fuid procurement an identification o individuals within a social seestem. Thay hae guid spatial discrimination abeelities an aw.[90] Studies hae assessed equine intelligence in auries sic as problem solvin, speed o learnin, an memory. Horse excel at semple learnin, but are able tae uise mair advanced cognitive abilities that involve categorisation an concept learnin an aw. Thay can learn uisin habituation, desensitisation, clessical condeetionin, an operant condeetionin, an positive an negative reinforcement.[90] Ane study haes indicatit that horse can differentiate atween "mair or less" if the quantity involved is less nor fower.[91]

Domesticatit horse mey face greater mental challenges nor wild horse, acause thay live in artifeecial environments that prevent instinctive behaviour whilst learnin tasks that are nae naitural.[90] Horse are ainimals o habit that respond well tae regimentation, an respond best whan the same routines an techniques are uised consistently. Ane trainer believes that "intelligent" horse are reflections o intelligent trainers wha effectively uise response condeetionin techniques an positive reinforcement tae train in the style that best fits wi an individual ainimal's naitural inclinations.[92]

Temperament

[eedit | eedit soorce]Horse are mammals, an as sic are wairm-bluidit, or endothermic craiturs, as opponed tae cauld-bluidit, or poikilothermic ainimals. Houever, thir wirds hae developed a separate meanin in the context o equine terminology, uised tae descrive temperament, nae bouk temperatur. For ensaumple, the "het-bluids", sic as mony race horse, exhibit mair sensitivity an energy,[93] while the "cauld-bluids", sic as maist draucht breeds, are quieter an calmer.[94] Whiles "het-bluids" are clessifee'd as "licht horse" or "ridin horse",[95] wi the "cauld-bluids" clessifee'd as "draucht horse" or "wark horse".[96]

Sleep patterns

[eedit | eedit soorce]Horse are able tae sleep baith staundin up an leein doun. In an adaptation frae life in the wild, horse are able tae enter licht sleep uisin a "stay apparatus" in thair legs, allouin them tae doze withoot collapsin.[97] Horse sleep better whan in groups acause some ainimals will sleep while ithers staund gaird tae watch for predators. A horse kept alane will nae sleep well acause its instincts are tae keep a constant ee oot for danger.[98]

Unlik humans, horse dae nae sleep in a solit, unbroken period o time, but tak mony short periods o rest. Horse spend fower tae fifteen oors a day in staundin rest, an frae a few meenits tae several oors leein doun. Tot sleep time in a 24-oor period mey range frae several meenits tae a couple o oors,[98] maistly in short intervals o aboot 15 meenits ilk.[99] The average sleep time o a domestic horse is said tae be 2.9 oors per day.[100]

Horse maun lee doun tae reach REM sleep. Thay anerly hae tae lie doun for an oor or twa ivery few days tae meet thair meenimum REM sleep requirements.[98] Houiver, if a horse is niver alloued tae lie doun, efter several days it will acome sleep-deprived, an in rare cases mey suddenly collapse as it involuntarily slips intae REM sleep while still staundin.[101] This condeetion differs frae narcolepsy, awtho horse mey suffer frae that disorder an aw.[102]

References

[eedit | eedit soorce]- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 73. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ↑ a b Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 630–631. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2003). "Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved. Opinion 2027 (Case 3010)". Bull. Zool. Nomencl. 60 (1): 81–84. Archived frae the original on 21 August 2007.

- ↑ Goody, John (2000). Horse Anatomy (2nd ed.). J A Allen. ISBN 0-85131-769-3.

- ↑ Pavord, Tony; Pavord, Marcy (2007). Complete Equine Veterinary Manual. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-1883-7.

- ↑ a b c d Ensminger, pp. 46–50

- ↑ Wright, B. (29 Mairch 1999). "The Age of a Horse". Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Government of Ontario. Archived frae the original on 20 Januar 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ↑ Ryder, Erin. "World's Oldest Living Pony Dies at 56". The Horse. Retrieved 31 Mey 2007.

- ↑ British Horse Society (1966). The Manual of Horsemanship of the British Horse Society and the Pony Club (6th edition, reprinted 1970 ed.). Kenilworth, UK: British Horse Society. p. 255. ISBN 0-9548863-1-3.

- ↑ "Rules of the Australian Stud Book" (PDF). Australian Jockey Club. 2007. p. 7. Retrieved 9 Julie 2008.

- ↑ a b "Equine Age Requirements for AERC Rides". American Endurance Riding Conference. Archived frae the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 25 Julie 2011.

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 415

- ↑ Becker, Marty, Audrey Pavia, Gina Spadafori, Teresa Becker (2007). Why Do Horses Sleep Standing Up?: 101 of the Most Perplexing Questions Answered About Equine Enigmas, Medical Mysteries, and Befuddling Behaviors. HCI. p. 23. ISBN 0-7573-0608-X.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors leet (link)

- ↑ a b c Ensminger, p. 418

- ↑ Giffin, p. 431

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 422

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 427

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 420

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 430

- ↑ "Glossary of Horse Racing Terms". Equibase.com. Equibase Company, LLC. Retrieved 3 Apryle 2008.

- ↑ "Rules of the Australian Stud Book". Australian Jockey Club Ltd and Victoria Racing Club Ltd. Julie 2008. p. 9. Retrieved 5 Februar 2010.

- ↑ Whitaker, p. 77

- ↑ Bongianni, entries 1, 68, 69

- ↑ Bongianni, entries 12, 30, 31, 32, 75

- ↑ Bongianni, entries 86, 96, 97

- ↑ Whitaker, p. 60

- ↑ Martin, Arthur (8 October 2006). "Meet Thumbelina, the World's Smallest Horse". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ↑ a b c Ensminger, M.E. (1991). Horses and Tack (Revised ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-395-54413-0. OCLC 21561287.

- ↑ Howlett, Lorna; Philip Mathews (1979). Ponies in Australia. Milson's Point, NSW: Philip Mathews Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 0-908001-13-4.

- ↑ "2012 United States Equestrian Federation, Inc. Rule Book". United States Equestrian Federation. p. Rule WS 101. Archived frae the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ "Annex XVII: Extracts from Rules for Pony Riders and Children, 9th edition" (PDF). Fédération Equestre Internationale. 2009. Archived frae the original (PDF) on 28 Januar 2013. Retrieved 7 Mairch 2010.

- ↑ For ensaumple, the Missouri Fox Trotter, or the Arabian horse. See McBane, pp. 192, 218

- ↑ For ensaumple, the Welsh Pownie. See McBane, pp. 52–63

- ↑ McBane, p. 200

- ↑ "Chromosome Numbers in Different Species". Vivo.colostate.edu. 30 Januar 1998. Archived frae the original on 11 Mey 2013. Retrieved 17 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Sequenced horse genome expands understanding of equine, human diseases". Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 1 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Domestic Horse Genome Sequenced". ScienceDaily, LLC. 5 November 2009. doi:10.1126/science.1178158. Retrieved 1 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ "Ensembl genome browser 71: Equus caballus - Description". Uswest.ensembl.org. Archived frae the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 17 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ Vogel, Colin B.V.M (1995). The Complete Horse Care Manual. New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 0-7894-0170-3. OCLC 32168476.

- ↑ Mills, Bruce; Barbara Carne (1988). A Basic Guide to Horse Care and Management. New York, NY: Howell Book House. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-87605-871-3. OCLC 17507227.

- ↑ Corum, Stephanie J. (1 Mey 2003). "A Horse of a Different Color". The Horse. Retrieved 11 Februar 2010. Unknown parameter

|registration=ignored (help) - ↑ a b c "Horse Coat Color Tests". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. University of California. Retrieved 1 Mey 2008.

- ↑ Marklund, L.; M. Johansson Moller; K. Sandberg; L. Andersson (1996). "A missense mutation in the gene for melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor (MC1R) is associated with the chestnut coat color in horses". Mammalian Genome. 7 (12): 895–899. doi:10.1007/s003359900264. PMID 8995760.

- ↑ a b "Introduction to Coat Color Genetics". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. University of California. Retrieved 1 Mey 2008.

- ↑ Haase B; Brooks SA; Schlumbaum A; et al. (2007). "Allelic Heterogeneity at the Equine KIT Locus in Dominant White (W) Horses". PLoS Genetics. 3 (11): e195. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195. PMC 2065884. PMID 17997609.

- ↑ Mau, C., Poncet, P. A., Bucher, B., Stranzinger, G. & Rieder, S. (2004). "Genetic mapping of dominant white (W), a homozygous lethal condition in the horse (Equus caballus)". Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics. 121 (6): 374–383. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0388.2004.00481.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors leet (link)

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 156

- ↑ Johnson, Tom. "Rare Twin Foals Born at Vet Hospital: Twin Birth Occurrences Number One in Ten Thousand". Communications Services, Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma State University. Archived frae the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ↑ Miller, Robert M.; Rick Lamb (2005). Revolution in Horsemanship and What it Means to Mankind. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 1-59228-387-X. OCLC 57005594.

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 150

- ↑ Kline, Kevin H. (7 October 2010). "Reducing weaning stress in foals". Montana State University eXtension. Archived frae the original on 22 Mairch 2012. Retrieved 3 Apryle 2012.

- ↑ Ensminger, M.E. (1991). Horses and Tack (Revised ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 129. ISBN 0-395-54413-0. OCLC 21561287.

- ↑ McIlwraith, C.W. "Developmental Orthopaedic Disease: Problems of Limbs in young Horses". Orthopaedic Research Center. Colorado State University. Retrieved 20 Apryle 2008.

- ↑ Thomas, Heather Smith (2003). Storey's Guide to Training Horses: Ground Work, Driving, Riding. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-58017-467-1.

- ↑ "2-Year-Old Racing (US and Canada)". Online Fact Book. Jockey Club. Retrieved 28 Apryle 2008.

- ↑ Bryant, Jennifer Olson; George Williams (2006). The USDF Guide to Dressage. Storey Publishing. pp. 271–272. ISBN 1-58017-529-5.

- ↑ Evans, J. (1990). The Horse (Second ed.). New York, NY: Freeman. p. 90. ISBN 0-7167-1811-1. OCLC 20132967.

- ↑ Ensminger, pp. 21–25

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 367

- ↑ Giffin, p. 304

- ↑ Giffin, p. 457

- ↑ Fuess, Theresa A. "Yes, The Shin Bone Is Connected to the Ankle Bone". Pet Column. University of Illinois. Archived frae the original on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 5 Apryle 2008.

- ↑ Giffin, pp. 310–312

- ↑ Kreling, Kai (2005). "The Horse's Teeth". Horses' Teeth and Their Problems: Prevention, Recognition, and Treatment. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot. pp. 12–13. ISBN 1-59228-696-8. OCLC 59163221.

- ↑ Giffin, p. 175

- ↑ a b Ensminger, pp. 309–310

- ↑ a b Sellnow, Les (2004). Happy Trails: Your Complete Guide to Fun and Safe Trail Riding. Eclipse Press. p. 46. ISBN 1-58150-114-5. OCLC 56493380.

- ↑ "Eye Position and Animal Agility Study Published". The Horse. 7 Mairch 2010. Retrieved 11 Mairch 2010. Press Release, citing February 2010 Journal of Anatomy, Dr. Nathan Jeffery, co-author, University of Liverpool.

- ↑ McDonnell, Sue (1 Juin 2007). "In Living Color". The Horse. Retrieved 27 Julie 2007. Unknown parameter

|registration=ignored (help) - ↑ Briggs, Karen (11 December 2013). "Equine Sense of Smell". The Horse. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Myers, Jane (2005). Horse Safe: A Complete Guide to Equine Safety. Collingwood, UK: CSIRO Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 0-643-09245-5. OCLC 65466652.

- ↑ Lesté-Lasserre, Christa (18 Januar 2013). "Music Genre's Effect on Horse Behavior Evaluated". The Horse. Blood Horse Publications. Retrieved 23 Januar 2013.

- ↑ Kentucky Equine Research Staff (15 Februar 2010). "Radios Causing Gastric Ulcers". EquiNews. Kentucky Equine Research. Retrieved 23 Januar 2013.

- ↑ Thomas, Heather Smith. "True Horse Sense". Thoroughbred Times. Thoroughbred Times Company. Archived frae the original on 28 Januar 2013. Retrieved 8 Julie 2008.

- ↑ Cirelli, Al Jr.; Brenda Cloud. "Horse Handling and Riding Guidelines Part 1: Equine Senses" (PDF). Cooperative Extension. University of Nevada. p. 4. Retrieved 9 Julie 2008.

- ↑ Hairston, Rachel; Madelyn Larsen (2004). The Essentials of Horsekeeping. New York, NY: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 77. ISBN 0-8069-8817-7. OCLC 53186526.

- ↑ Miller, p. 28

- ↑ Gustavson, Carrie. "Horse Pasture is No Place for Poisonous Plants". Pet Column July 24, 2000. University of Illinois. Archived frae the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 9 Julie 2008.

- ↑ Harris, p. 32

- ↑ Harris, pp. 47–49

- ↑ "Fastest speed for a race horse". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 8 Januar 2013.

- ↑ Harris, p. 50

- ↑ Lieberman, Bobbie (2007). "Easy Gaited Horses". Equus (359): 47–51.

- ↑ Equus Staff (2007). "Breeds that Gait". Equus (359): 52–54.

- ↑ Harris, pp. 50–55

- ↑ "Horse Fight vs Flight Instinct". eXtension. 24 September 2009. Archived frae the original on 15 Mey 2013. Retrieved 17 Apryle 2013.

- ↑ McBane, Susan (1992). A Natural Approach to Horse Management. London: Methuen. pp. 226–228. ISBN 0-413-62370-X. OCLC 26359746.

- ↑ Ensminger, pp. 305–309

- ↑ Prince, Eleanor F.; Gaydell M. Collier (1974). Basic Horsemanship: English and Western. New York, NY: Doubleday. pp. 214–223. ISBN 0-385-06587-6. OCLC 873660.

- ↑ a b c Clarkson, Neil (16 Apryle 2007). "Understanding horse intelligence". Horsetalk 2007. Horsetalk. Archived frae the original on 24 Januar 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ↑ Lesté-Lasserre, Christa. "Horses Demonstrate Ability to Count in New Study". The Horse. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ↑ Coarse, Jim (17 Juin 2008). "What Big Brown Couldn't Tell You and Mr. Ed Kept to Himself (part 1)". The Blood Horse. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ↑ Belknap, p. 255

- ↑ Belknap, p. 112

- ↑ Ensminger, pp. 71–73

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 84

- ↑ Pascoe, Elaine. "How Horses Sleep". Equisearch.com. Archived frae the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 Mairch 2007. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ a b c Pascoe, Elaine (12 Mairch 2002). "How Horses Sleep, Pt. 2 – Power Naps". Equisearch.com. Archived frae the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 Mairch 2007.

- ↑ Ensminger, p. 310.

- ↑ Holland, Jennifer S. (Julie 2011). "40 Winks?". National Geographic. 220 (1).

- ↑ EQUUS Magazine Editors. "Equine Sleep Disorder Videos". Equisearch.com. Archived frae the original on 10 Mey 2007. Retrieved 23 Mairch 2007. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ Smith, BP (1996). Large Animal Internal Medicine (Second ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. pp. 1086–1087. ISBN 0-8151-7724-0. OCLC 33439780.

Soorces

[eedit | eedit soorce]- Belknap, Maria (2004). Horsewords: The Equine Dictionary (Second ed.). North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square Publishing. ISBN 1-57076-274-0.

- Bongianni, Maurizio (1987). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Horses and Ponies. New York: Fireside. ISBN 0-671-66068-3.

- Dohner, Janet Vorwald (2001). "Equines: Natural History". In Dohner, Janet Vorwald (ed.). Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Topeka, KS: Yale University Press. pp. 400–401. ISBN 978-0-300-08880-9.

- Edwards, Elwyn Hartley (1994). The Encyclopedia of the Horse. London, UK: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 1-56458-614-6. OCLC 29670649.

- Ensminger, M. E. (1990). Horses and Horsemanship: Animal Agricultural Series (Sixth ed.). Danville, IN: Interstate Publishers. ISBN 0-8134-2883-1. OCLC 21977751.

- Giffin, James M.; Tom Gore (1998). Horse Owner's Veterinary Handbook (Second ed.). New York: Howell Book House. ISBN 0-87605-606-0. OCLC 37245445.

- Harris, Susan E. (1993). Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement. New York: Howell Book House. ISBN 0-87605-955-8. OCLC 25873158.

- McBane, Susan (1997). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Horse Breeds. Edison, NJ: Wellfleet Press. ISBN 0-7858-0604-0. OCLC 244110821.

- Miller, Robert M. (1999). Understanding the Ancient Secrets of the Horse's Mind. Neenah, WI: Russell Meerdink Company Ltd. ISBN 0-929346-65-3. OCLC 42389612.

- Price, Steven D.; Spector, David L..; Gail Rentsch; Burn, Barbara B. (editors) (1998). The Whole Horse Catalog: Revised and Updated (Revised ed.). New York: Fireside. ISBN 0-684-83995-4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors leet (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors leet (link)

- Sponenberg, D. Phillip (1996). "The Proliferation of Horse Breeds". Horses Through Time (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 1-57098-060-8. OCLC 36179575.

- Whitaker, Julie; Whitelaw, Ian (2007). The Horse: A Miscellany of Equine Knowledge. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-37108-X.